Obituary: Sir Harold Evans

- Published

Sir Harold Evans, who has died aged 92, was a legend among journalists.

His campaigns against injustice and for the highest journalistic standards forged his reputation.

During his tenure as editor of the Sunday Times, he turned the paper into a beacon for crusading journalism.

His finest moment was probably his campaign for the families of children who suffered birth defects as a result of the drug Thalidomide.

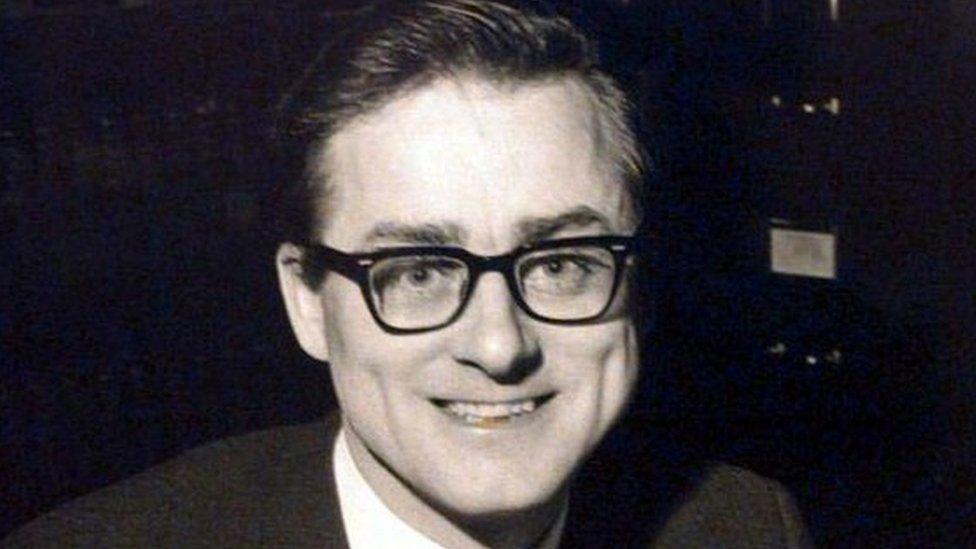

Harold Evans was born on 28 June 1928 in Eccles, Lancashire, now in Greater Manchester, the son of Welsh parents.

His father was an engine driver while his mother ran a small grocery shop from the family home. Evans later described them as "the self-consciously respectable working class".

He would later recall the "mythic north of my childhood," where "there was comfort in being rooted in a community and recognised within it as a good neighbour".

He left school at 16 and wrote applications to every newspaper in the Manchester area, finally securing a job at the Ashton-under-Lyne Reporter.

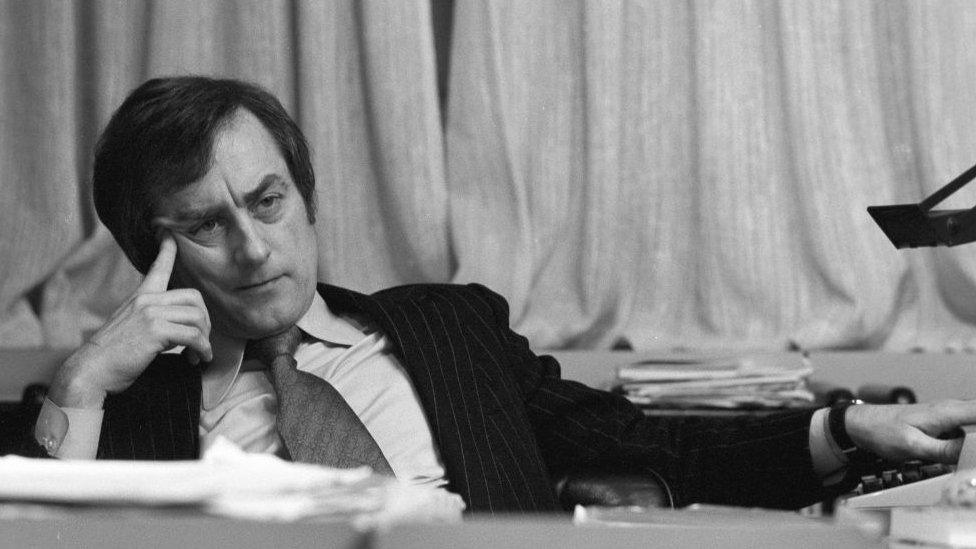

The crusading editor of the Northern Echo

It was, he recalled, a paper that "bothered with the little things in people's lives, the whist drives and flower shows".

After National Service he adopted the same tenacious approach and wrote to every university in the UK - there were just 14 in those days - finally landing a place at Durham. There he read politics and economics and edited the university magazine, The Palatinate.

He forged his reputation as assistant editor of the Manchester Evening News, which he joined in 1952, in a city, he said, that "simply throbbed with news day and night".

It was in the United States, where he travelled for two years on a Harkness Fellowship, that he got the taste for investigative journalism.

Polluting

America did not have the same dominant national newspapers that flourished in Britain - neither did US journalists share the awe of the establishment that still pervaded the press in the UK.

The crusading ambitions of local US papers were also in sharp contrast to the rather mundane local press Evans knew at home.

On his return he had the opportunity to put what he had learned into practice when he was appointed editor of the Northern Echo, based in Darlington.

Evans was determined to put Darlington, and the Echo, on the national stage.

The Sunday Times campaign resulted in increased compensation for those affected by Thalidomide

He persuaded the BBC in Newcastle to make a documentary showing him at work and reorganised the paper's bureaucratic hierarchy.

One of his first campaigns was against the chemical giant ICI, whose plant at Billingham was polluting the area with a noxious smell.

Criticised by local dignitaries for attacking one of the area's biggest employers, Evans persevered and finally got an admission from the company that it had problems with leaks at the plant.

Other investigations resulted in a national screening programme for cervical cancer and he was part of the campaign to secure a posthumous pardon for Timothy Evans, wrongly hanged for murder in 1950.

Compensation

His own profile was raised by appearances on the TV programme What the Papers Say. In 1964 he was offered the job of managing editor at the Sunday Times.

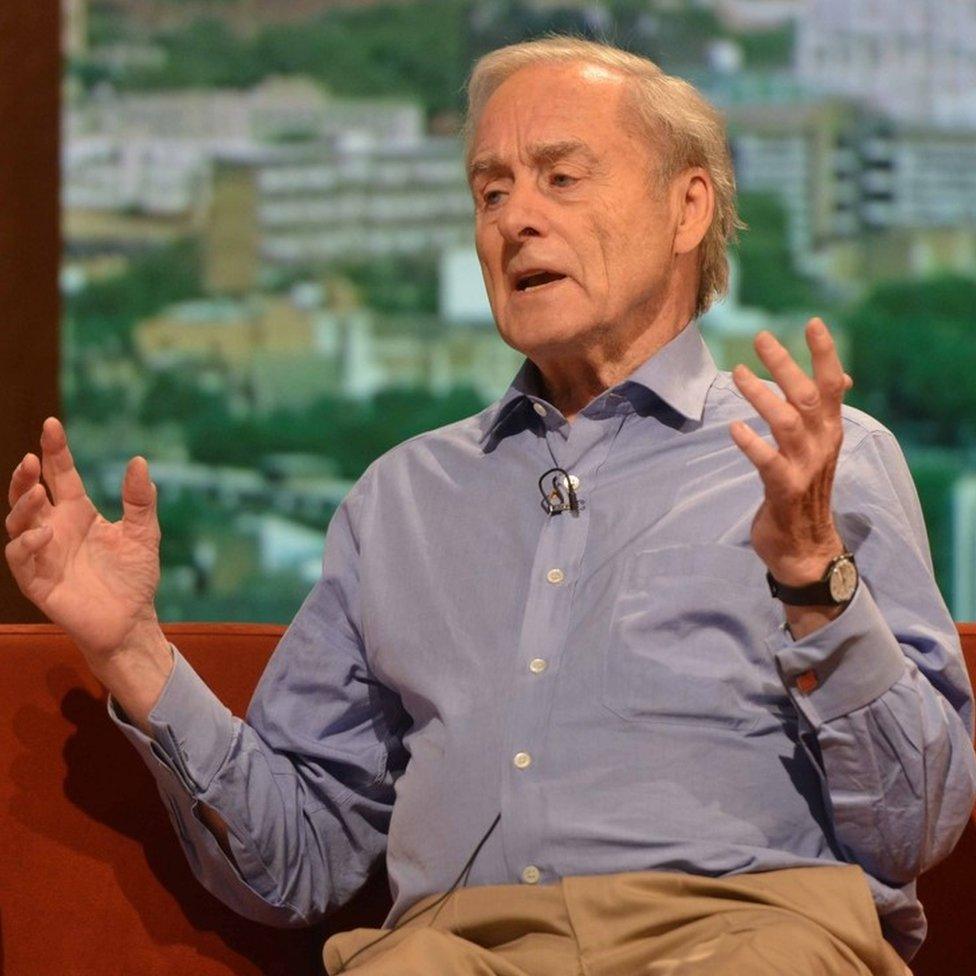

When the editor left shortly afterwards, Evans got the job. He also inherited the newly created Insight team of investigative journalists. It was manna from heaven for his own crusading instincts.

During his 13 years at the helm, the paper's most notable campaign was fighting for greater compensation for those affected by Thalidomide.

The drug, which first appeared in the UK in 1958, was prescribed to expectant mothers to control the symptoms of morning sickness.

Evans (L) did not long survive Murdoch's takeover of the newspaper

However, hundreds of these mothers in Britain, and many thousands across the world, gave birth to children with missing limbs, deformed hearts, blindness and other problems.

Evans's campaign, launched in 1972, eventually forced the UK manufacturer, Distillers Company - at the time the Sunday Times's biggest advertiser - to increase the compensation payments.

It also forced a change in UK law to allow the open reporting of civil cases, something that had hampered the sort of journalism Evans espoused.

His team's tenacious investigation into the Turkish Airlines DC-10 air crash outside Paris in 1974, which killed 346 people, resulted in an admission that poor maintenance on a faulty cargo door had caused the crash.

'Evil incarnate'

This led to families of the victims receiving more than $60 million in compensation.

He insisted campaigns should be selective and deplored what he saw as the invasion of privacy by the British tabloid press.

His tenure at the Sunday Times came to an end following a strike by print unions that closed the paper for a year and forced the proprietor, Roy Thomson, to sell Times Newspapers to Rupert Murdoch.

Murdoch offered him the editorship of the Times but Evans quit months later after falling out with the Murdoch management team.

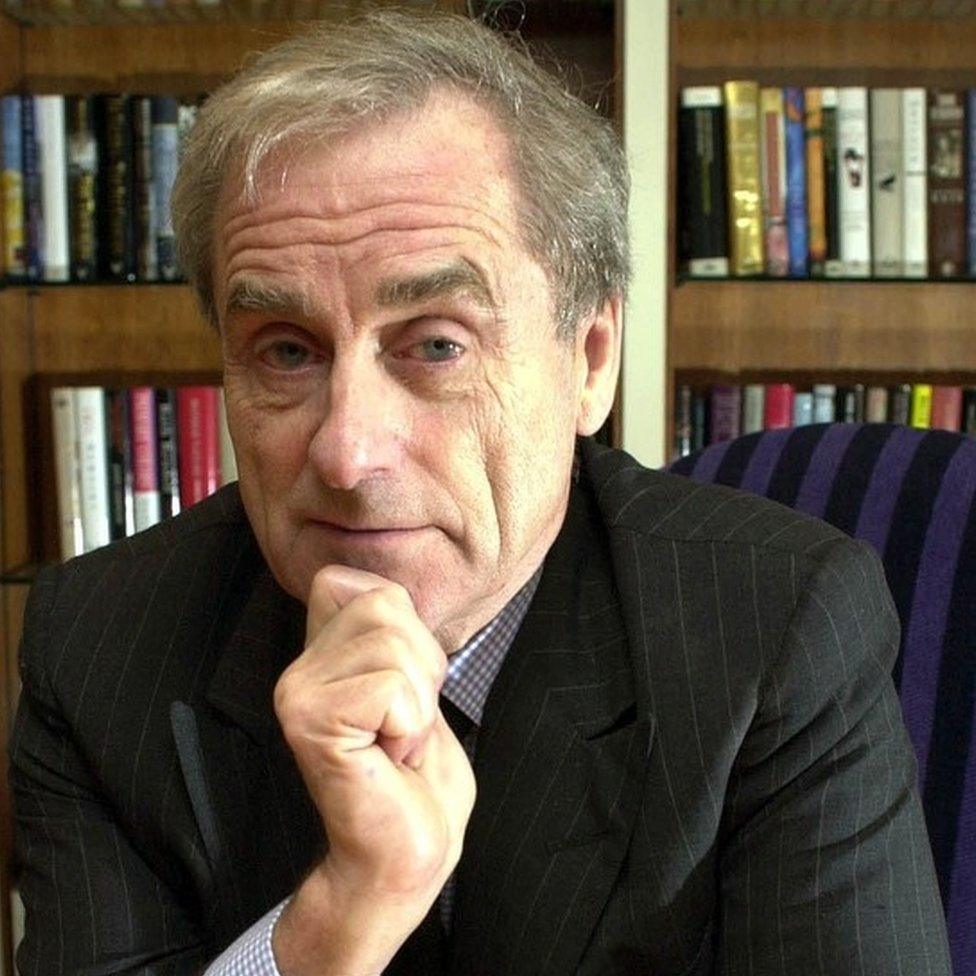

He forged a new career in the United States

He later described Rupert Murdoch as "evil incarnate" when giving evidence to the Leveson Inquiry in 2012.

Having divorced his first wife in 1978, he married the journalist Tina Brown, and the couple moved to New York.

There he remained seemingly glad to have left Britain and talked of '"the position of respect held by the journalist in American society".

While she edited Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, he became founding editor of Conde Nast Traveler magazine and later president of the publishing giant, Random House.

Determined

The couple became leading socialites on the New York scene - their legendary parties were attended by the great and the good. Although he became an American citizen, he maintained dual citizenship.

After seven years at Random House, Harold Evans became editorial director of a group of publications that included the tabloid New York Daily News, as well as several magazines including US News and World Report and the Atlantic Monthly.

He left in 1997 to concentrate on writing, producing the critically acclaimed The American Century and its sequel, They Made America, which described the lives of some of the country's most important inventors and innovators.

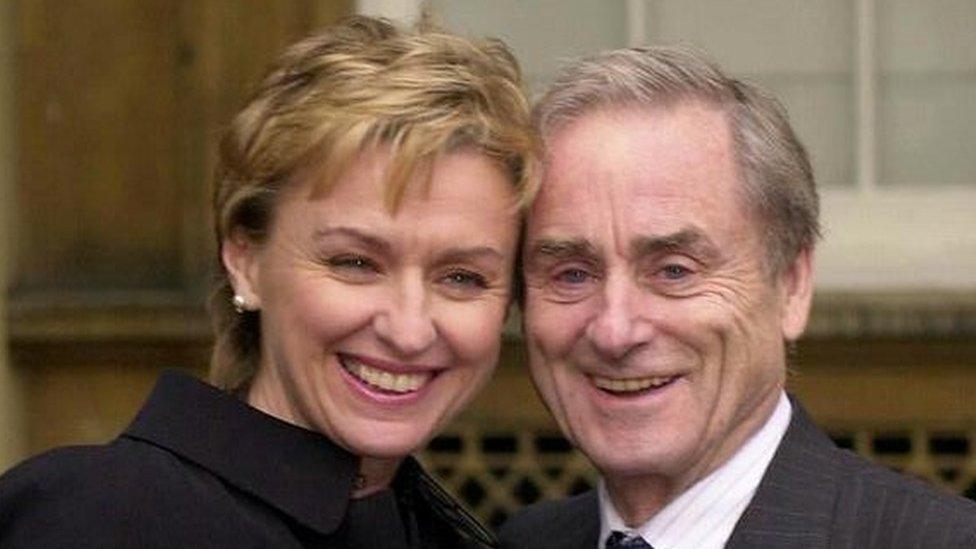

He and his wife Tina Browne became noted New York socialites

Evans's reputation was confirmed when he was voted the all-time greatest newspaper editor by his peers in 2002 and was knighted in 2004 for his services to journalism.

He was passionate about newspaper journalism to the end, saying in his 2009 memoirs My Paper Chase: "It's endlessly fascinating to me how the tumult of the world can be made comprehensible by the orderly calibration of values within the discipline of the printed page."

In 2011, at the age of 82, he was appointed editor at large at the Reuters news agency, the organisation's editor-in-chief describing him as "one of the greatest minds in journalism".

The former Sunday Times Insight editor, Bruce Page, once described Evans as "the most considerable editor of post-war history: courageous, determined, with extraordinary presentational flair, and a great technician who understood the craft of newspapers".

- Published24 September 2020