Museums enjoy 10 years of freedom

- Published

Museums that allow free entry include (clockwise from top left) the Victoria & Albert, Merseyside Maritime, Science and Natural History Museums

Exactly 10 years ago, museums and galleries - including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Natural History Museum - scrapped entrance fees as part of a government plan to widen access to the nation's culture and heritage.

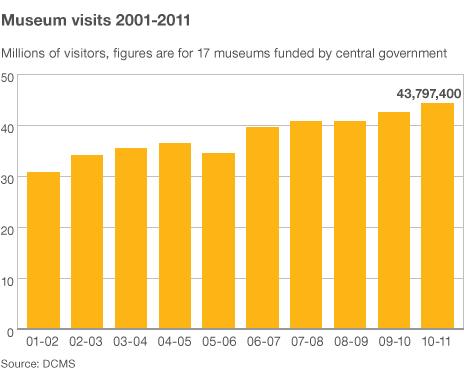

Visitor numbers have shot up - but who has really benefited, and can free admission survive in an age when government funds are stretched to the limit?

When then Culture Secretary Chris Smith guaranteed that flagship museums and art galleries would be free, he promised that it would herald "an exciting new beginning for the arts and cultural life of this country".

Ten years on, Smith, now Baron Smith of Finsbury, says the success of the policy has exceeded his expectations.

"I was pretty sure that the reintroduction of free admission would increase the number of people coming into museums and galleries, but what I hadn't envisaged was that the numbers were going to rise quite so dramatically," he says.

The headline figures are clear. Government-sponsored museums where entry became free from 2001 have seen their combined visitor numbers rise from seven million to almost 18 million over the course of a decade.

Some venues were already free before 2001, such as the British Museum and the Tate. After 2001, their government funding was granted on the condition that they stayed free.

"It was about opening up the great institutions, making history, and art and culture, available to the widest possible number of people - and bringing a sense to everyone that these were possessions that we all owned and shared," Lord Smith says.

Numbers soared across the board, but one key question is whether the policy has attracted new people to these institutions - or whether members of the middle classes are just visiting more often.

In 2003, a Mori survey found an increase in visitors from the lower social classes - but among all other groups, the balance remained largely the same.

"While the number of people coming through the door might have dramatically increased, the profile of a typical 'population' of museum or gallery visitors has remained relatively stable, and firmly biased in favour of the 'traditional' visitor groups," the report said.

In 2005, 28% of people from lower economic groups said they had visited a museum or gallery in the past year. That figure was up to 34% last year. Earlier comparable figures are not available because the method of measuring social and economic groups changed in 2005.

The institution with the most visitors from the lower social groups is National Museums Liverpool, which runs seven venues, including the Merseyside Maritime Museum, the World Gallery and the Walker Art Gallery.

It also operates the recently-opened Museum of Liverpool, which is hosting the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh on Thursday to open four new galleries.

Its venues had 738,000 visits from adults in the lower half of the Office for National Statistics' social and economic scale, in 2010/11 - more than the British Museum, Imperial War Museums, National Maritime Museum, National Portrait Gallery and Victoria and Albert Museum put together.

National Museums Liverpool director David Fleming says free entry is key to attracting a broad audience, and that a wide variety of exhibitions has pulled in people across age and class divides.

"We look for things that are challenging and intelligent, and also have appeal across generations," he says.

"A good example recently is to have Lily Savage's dresses alongside Matisse drawings. That's the kind of variety I think that a great museum tries to achieve. You don't just do one. You don't just do the other. You try to mix it up.

"Just putting on posh art exhibitions doesn't do it for most people. That tends to attract the same people time after time after time."

Four out of 10 adult UK-based visitors to the Liverpool venues are classed in the lower social groups. For most of the big London institutions - including the British Museum, National Gallery, Tate and V&A - the figure is one or two out of 10.

Some capital venues, such as the Natural History Museum and National Gallery, meanwhile, recorded more than 20% of visitors from ethnic minorities.

Changing image

That reflects the different population profiles of Liverpool and London, according to Michael Dixon, director of the Natural History Museum and chair of the National Museum Directors' Conference.

"I would refute the suggestion that we've failed because both the percentages and the absolute numbers have gone up rather impressively," he says.

Venues have staged a wider variety of exhibitions in order to bring in new people, while free entry has changed the image of museums, he believes.

"We have quite demonstrably tried to run public programmes that will interest black and minority ethnic groups and bring them into the museum," he says.

"When we do bring them in and engage with them very actively, their perceptions about museums change and they do see them as viable and relevant to them."

One argument against free admission is that it damages those venues that do charge.

Bill Ferris, who runs Chatham Historic Dockyard in Kent, and is vice-chairman of the Association of Independent Museums, says some people prefer to travel to London to avoid paying his entry fee, while others turn up expecting all museums to be free.

"Government ministers tend to stand up and talk about museums being free, and museums are very expensive organisations to run and manage," he says.

"A few benefit from national sponsorship, which allows them free entry, but more than 50% of British museum stock is independent and relies on visitor admissions to help fund them.

"It's wonderful that people can see important objects for free, but it does cause a market distortion and a misunderstanding among the public."

'Tipping point'

After 10 years, free admission to national museums is an accepted part of British cultural life. No major political party opposed it at last year's general election.

Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt says he has "secured the future of free museums, despite the current financial climate".

But with government budgets under pressure, national museums have had their funding cut by 15%. Despite Hunt's assurances, a rethink on free entry from either the government, or the museums themselves, cannot be ruled out.

Michael Dixon praises Hunt for fighting to preserve free entry, but warns: "Clearly there is a tipping point where you just cannot keep taking cash away from institutions like this and expect us still to deliver the frontline services that we do.

"So there is definitely a tipping point beyond which government cuts would force our boards to look at whether it is possible to sustain free admission."

- Published1 December 2011

- Published1 December 2011