Simon Armitage pays tribute to 'one-off' Ted Hughes

- Published

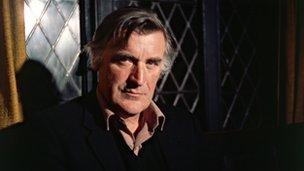

Hughes's work held complex ideas but was still understandable to all, says Armitage

At a service on the 6 December the name of Ted Hughes, former Poet Laureate, will take its place in the South Transept of Westminster Abbey, in that part of the building colloquially known as Poets' Corner.

Geoffrey Chaucer, one of the founding fathers of British poetry, was buried here, and although he was being recognised as an employee of the Abbey rather than for anything he had written, the practice of honouring the greatest poets of the age with a tomb or a stone has developed into a 600-year tradition.

Dryden, Tennyson, Browning and Hardy are buried in Poets' Corner, and Milton, Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, Blake, Hopkins and Eliot are memorialised there. It is, is could be argued, poetry's most exclusive club, or as close as a poet might come to immortality here on earth.

Hell-raisers like Byron have to wait for the scandal to die down and the dust to settle before being offered a berth in such sacred surroundings, though why it has taken 13 years of questioning and campaigning for Hughes to be recognised in this way is something of a mystery.

For Armitage Birthday Letters encapsulated all that was great about Hughes

Edward James Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd in West Yorkshire in 1930, and right from the outset his tone of voice and subject matter set him apart from other poets of his generation.

Compared with the urban and urbane styles of his post-war contemporaries whose poems often looked like crossword puzzles or elaborate word-games, Hughes's approach was elemental and unpretentious, almost as if the poems had grown out of the earth.

He came to immediate attention with his first book, Hawk in the Rain, and from that moment on was never far from the literary headlines, either because of the singular quality of his work or through his now infamous marriage to Sylvia Plath and her subsequent suicide.

When another lover took her own life and that of their daughter, Hughes's name was forever linked with tragedy and the sensationalism that accompanies it, though the writing never stopped, and included work for children, theatre, radio, critical commentaries, translation and always, at the heart of it, poetry.

'Acts of magic'

In 1998 he published Birthday Letters, his belated poetic response to the all-too-public terrors of his personal life. Birthday Letters became that rare thing - a poetry bestseller - and one in which the potentially explosive subject matter was brought under control through the measured artistry of his writing. Hughes won the Whitbread Book prize twice.

Hughes unveiled a memorial to World War I poets in Westminster Abbey in 1985

For me, Birthday Letters was a reminder of what I had felt all along, that Hughes was a one-off, a writer with an unparalleled natural gift, a once-in-a-generation poet, whose work was a major contribution to English Literature.

Reading his poems in the classroom at school all those years ago had been like experiencing spell-binding acts of magic.

When he wrote about a bull, I could smell it; when he wrote about a jaguar, I could sense it to the point where the hairs on the back of my neck stood up; when he wrote about a bayonet charge, I wasn't just witnessing it, I was experiencing it, going over the top in the "cold clockwork of the stars and nations," into the bullets and bombs.

Those were adult poems, germinating and burgeoning and multiplying wildly in my young imagination, something that several generations of students have gone on to appreciate.

For although Hughes's themes are often complex and cerebral, his poetry is nearly always approachable and engaging, even to the common reader.

It is a balance that not all writers understand and even fewer achieve, and one of the main reasons I believe we will still be reading Hughes (assuming we will be "reading" at all) in future centuries.

Hughes was only 68 when he died, and at that time Seamus Heaney was moved to describe him as "a guardian spirit of the land and language".

In those terms, it seems entirely fitting that this great man of words should take his place in such hallowed ground, among his forbears and equals.

- Published2 November 2011