Close the Coalhouse Door delivers miners' message

- Published

.jpg)

Mining is a theme in Lee Hall's work from Billy Elliot to The Pitmen Painters. Photo: NCJ Media

Director Samuel West and writer Lee Hall hope a revival of Alan Plater's 1968 play Close the Coalhouse Door can teach a new generation about fighting for their rights.

When I put my first question to Samuel West, a simple query about his motivation for staging Close the Coalhouse Door, he begins his answer with the words: "I make no secret of the fact that I disagree with the direction of our current government..."

The play is 44 years old and centres on the lives of miners in Newcastle, so it may seem odd that the conversation immediately turns to modern politics.

But Samuel West - the actor-director who starred in Howard's End and the play Enron - and Billy Elliot writer Lee Hall are both political animals.

So it soon transpires that there is more to this revival, which opens at Northern Stage in Newcastle on Friday, than just the resurrection of a neglected theatrical treasure.

When the play first came to the city in 1968, it was a massive hit.

Stories of pitmen going to the theatre instead of the football on a Saturday afternoon, and of coachloads of miners rolling up at the theatre in their Sunday best, have passed into local legend.

Actor-turned-director Samuel West: "It was a story that needed to be told." Photo: Topher McGrillis

The plot revolves around a Newcastle family looking back on 140 years of miners' struggles against pit-owners and politicians.

But Plater's irreverent saga of bickering brothers and plucky underdogs, coupled with songs by Alex Glasgow, is more than just a dry lesson in the history of industrial relations.

Starting in the 1830s, it recounts how pioneering unions formed, and went on strike, in protest at long hours worked by young boys and "bonds" that tied miners to punishing rules and conditions.

By joining together for strength in the face of hardship, the miners gradually won more rights as the decades wore on.

"The play becomes very relevant because it is a celebration of having collectively achieved something as a nation that I think we're in danger of throwing away," says Hall.

"It's a reminder that the life we rely on now was not always the case. People had to fight for it."

Close the Coalhouse Door opens at Northern Stage in Newcastle before going on a UK tour

The play has lessons for people hit by of the current financial crisis and austerity cuts, he believes.

"There's a feeling now that it's so hopeless and there's nothing we can do and we just have to put up with it because it's the inexorable forces of history and economics.

"[In the play] you see that every 30 or 40 years, just in one industry alone, exactly the same things happen again and again.

"But what they didn't do was just to sit and take it. What they did do was to fight back."

The play is "very provocative" in today's climate, he says.

West, the son of British acting legends Timothy West and Prunella Scales and a former member of the Socialist Workers' Party, is similarly strident.

He accuses the coalition government of using the financial crisis as "an excuse" to reduce living standards and turn individuals against each other.

The play was televised by the BBC in 1968

"That's not how progress is made and it isn't how the miners progressed in this country," he says. "I thought it was a story that needed to be told, really."

West winces at the thought he is "preaching" and insists it is a good piece of theatre. "It's not at all narrow agitprop."

Many people will disagree with the pair's politics and with Plater's interpretation of history, which firmly pits the gutsy workers against the evil elite.

And while it was a hit in Newcastle first time around, the play was a flop when it moved to the West End.

The north-east folk story, dominated by the mining industry's heroes and villains, did not strike a chord in London. The thick Geordie brogue probably did not help.

This time the show, a co-production between Northern Stage and Live Theatre in Newcastle, is going on tour after its run in the city.

Hall and West are confident that it will fare better in places like Richmond-upon-Thames, Guildford and Oxford than it did in the West End.

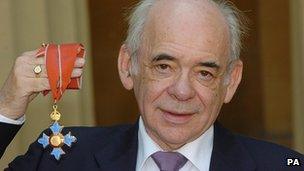

Alan Plater was made a CBE for services to drama in 2005, five years before his death

For the new version, Hall, a friend and protege of Plater, has added a short scene at the beginning to take people back to 1968, and one at the end that gives the 1968 family's rose-tinted vision of how the next 44 years would pan out.

Unfortunately, Newcastle United have not ended up as winners of the European Cup for 15 years in a row.

But Hall and West want the miners of the past to deliver a serious message to the audiences of the present. So what difference can a show like this really make?

"I'm not sure that plays can make any difference, but they can make people think," Hall says.

"If it reminds one single person that what is purported to be inevitable is not inevitable, then it will have been worth reviving.

"I think its big message is that the people of the 99%, the ordinary people, have some power and can alter things. I think it's a timely reminder to people that that is the case."

- Published30 March 2012

- Published7 July 2011

- Published8 April 2011

- Published25 June 2010