Is this the year of disability on TV?

- Published

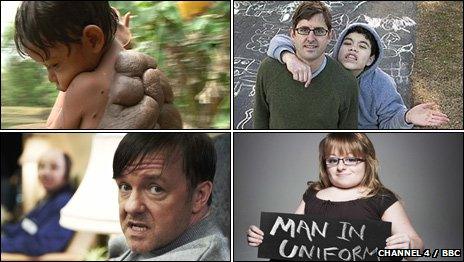

Clockwise from top left: Body Shock - Turtle Boy, Louis Theroux's Extreme Love, The Undateables, Derek

From prime time documentaries about "undateable" people and autism, through to sitcoms from world-renowned comedians, disability is currently more visible on TV than ever before.

Disabled campaigners have been crying "more" for years, but why is there a sudden glut of these television programmes and are they giving the right kind of attention?

"It feels like it's motoring a bit now, doesn't it." says Alison Walsh, Channel 4's disability advisor.

She has been trying to coax and persuade her channel's commissioners and programme makers to consider disability more for nearly 20 years.

"I don't know if there has been a change in general perceptions or what people look for in television programmes but it feels a bit more free, somehow."

The Undateables followed a group of disabled people trying to find love

This year, the channel will be the home of Paralympics coverage.

Their recent three-parter The Undateables followed nine people as they went on first dates and had the tagline: "Love is blind, disfigured, autistic" - a reference to its memorable contributors. The 'un' part of the title was seen to be shot down by a cupid's arrow in the title sequence.

"The viewing figures were so good and it seems to be a really positive show while not underplaying any of the differences some contributors have," says Walsh who is herself disabled. "There's humour, warmth and affection."

The Undateables finished last Tuesday, There was some criticism of its marketing but it certainly got the nation talking.

It was quickly followed by BBC Two's Extreme Love, an exploration of parents' relationships with their autistic children from Louis Theroux, which was well-received.

This week, the ball was back in Channel 4's court with "Turtle Boy", part of their Body Shock series and part of the genre sometimes referred to as "extreme biology" - which is often associated with shows on Channel 5 whose titles start "The boy with..."

Disabled TV maker Kate Monaghan, 28, is director of Markthree Media. She describes the recent strain of disability television programmes as "freak shows with a heart".

She says: "I think that we went through a period when disability on TV was about freak shows, like extraordinary people with three heads. Then we went into a backlash and no-one knew how to do disability."

Monaghan thinks that it's only been in the last year or so that people have been trying to improve the situation, and have begun to realise disability stories are interesting.

"I think disability is becoming more mainstream. I don't know if that's through media portrayals, or perhaps because disabled people are getting louder on social media, with recent Twitter campaigns feeding into newspapers which then feeds into other media.

"But I do believe that the Paralympics' influence, especially on Channel 4, is heightening interest."

'Stereotypes'

It wasn't that long ago that disabled people were perceived to be rarely seen on television at all. So, back then, when they did make an appearance, it was even more crucial to individuals and campaigning groups that the portrayals were positive ones.

In 1992, disability campaigners protested en masse outside London Weekend Television when it held the 28-hour ITV Telethon in the belief that the "pitiful" stereotypes in their charity appeal films did not help them achieve equality.

At the time, campaigner Rachel Hurst told The Independent newspaper: "What Telethon and programmes like it should be doing is encouraging able-bodied people to make disabled people members of their pubs and clubs, to employ them, let them into their schools, give them reasonable access to public places.

"We need that much more than the money raised from donations - which doesn't amount to a great deal anyway."

Since then, the Disability Discrimination Act has been implemented. Disabled people now have specific rights and the whole landscape feels different - with a generation of younger disabled people seemingly growing up feeling more empowered.

And now that disabled people are seen on television a little more frequently, that debate is less about "how often" and more about "how".

Kate Monaghan echoes many when she says she wants to see disabled people in all programmes: "I don't think people are getting it quite right yet... It would be better if it was done in a more mainstream way.

"Rather than 'here's a programme about disabled people' it should be 'here's a programme' and disabled people are just involved."

There will be more than 150 hours of Paralympic sport on TV this summer

The disability community is a huge and complex one, however.

Often we're not just talking about disabled people themselves but also the family and carers closely intertwined in their lives and daily decision making.

Many disabled people shun the defining term "disabled", for instance, and would be horrified if you tried to label them so negatively; others embrace it wholeheartedly.

Alison Walsh says it's difficult to make everyone happy, as all the stakeholder organisations they work with when consulting on their programmes have different agendas. One of the recurring debates is indeed about language.

"There's the debate about using 'disabled people' or 'people with disabilities'," she says.

"I've been through different phases of 'able-bodied' or 'non-disabled'.

"What's more important is authenticity and truthfulness, getting talent casting right, getting it credible, so the people we have on the screen look as if they're there because they're right for the programme not box ticking."

Walsh mentions a letter she saw in the Telegraph last week from former Blue Peter editor Biddy Baxter who, some thirty years on, is still defending the now-infamous use of Joey Deacon as a contributor.

"She referred to him as a quadriplegic spastic," she says. "I thought 'that's interesting.'

"They're words we try to expunge from the language but it doesn't always work. For some people of a certain generation, they're still using them."

The Paralympics is likely to draw an unusually big television audience this year, as it is being held in our own country.

The International Paralympic Committee chair, Philip Craven, has stated he believes the Games will leave a positive legacy when it comes to the perception of disabled people, helped by the fact it will be televised "more than ever" in London.

The BBC has been the home of Paralympics until now - but this time lost out to fellow public service broadcaster Channel 4 in bidding for the television rights. There will be at least 150 hours of coverage from the event, with extra programmes focussing on disabled athletes supporting the event.

Channel 4's That Paralympic Show, which deals with "all things Parasport", will be joined by BBC Two drama, Best of Men, which tells the story of a neurological doctor whose work with wounded soldiers led to the first official Paralympics in Rome in 1960.

BBC 5 live, meanwhile, will cover the Games on radio for those who can't get to a television.

- Published3 April 2012

- Published12 April 2012

- Published9 April 2012

- Published26 April 2012

- Published19 April 2012