Obituary: Eric Sykes

- Published

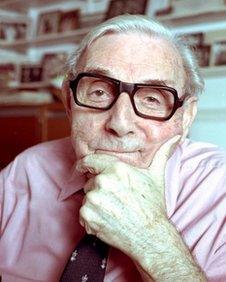

Eric Sykes called comedy a "calling"

Long, lean and lugubrious, Eric Sykes, who has died at the age of 89, starred for many years in his own television series, Sykes And A...

It cast him as the inoffensive inhabitant of 24 Sebastopol Terrace, constantly beset by the problems of domestic life.

The comedian's suburban adventures and gentle offbeat humour first went out on television in 1960 and delighted audiences of up to 20 million.

Sykes the performer never minded such a large audience. But Eric Sykes the person was far more of a recluse.

He was born on 4 May, 1923 in Oldham, Lancashire, the son of a millworker. His mother died while giving birth to him and his father remarried a year later.

At school he excelled in art. But his family could not afford to send him to college, so he became a store keeper in a cotton mill.

Wartime service gave him the chance to shine in several Royal Air Force entertainment shows, as well as a role in the Normandy landings.

Ever modest, Sykes maintained he had bluffed his way into those wartime shows.

"They asked if I had theatrical experience and I thought, I'd been to the theatre three times before the war."

Nonetheless, after World War II, he decided to make his living writing comic scripts.

His first break came when he managed to sell one to Frankie Howerd for £10. Before long he was writing regularly for radio.

Milligan partnership

One of the programmes was Educating Archie, on which he worked with Hattie Jacques, Max Bygraves and Tony Hancock. By the 1950s he had become the highest paid scriptwriter in Britain.

He offered simple, innocent humour devoid of malice, writing for such big stars of the day as Peter Sellers and Professor Stanley Unwin.

Hattie Jacques played Eric's sister in Sykes

But he also wrote for the surreal, cult comedy The Goon Show.

He was brought on board in 1954, partly to help ease the workload of the show's co-creator, Spike Milligan.

For a time they worked together in a single office. When the show left the airwaves in 1960, they continued their partnership on its TV spin-offs.

Even after Milligan's death in 2002, Sykes demanded that his receptionist answered the office phone by saying: "Spike Milligan and Eric Sykes' office."

"I know he's dead but we shared offices together for 50 years," Sykes told <link> <caption>Metro</caption> <url href="http://www.metro.co.uk/showbiz/interviews/13330-eric-sykes-im-a-master-of-my-craft-not-a-genius" platform="highweb"/> </link> earlier this year.

"He passed on ahead of me. He was going to do it before me, to see what it was like, for my benefit.

Plank success

Following his big-screen debut in Orders are Orders in 1954, Sykes went on to appear in more than 20 films.

These included Heavens Above!, Monte Carlo or Bust, Absolute Beginners, The Spy with a Cold Nose and Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines.

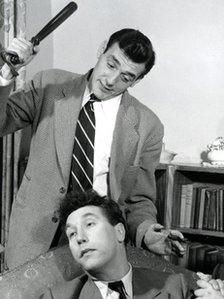

Sykes got his big break writing for Frankie Howerd (bottom of picture)

In 1967 Sykes made the acclaimed film The Plank, playing the archetypal workman alongside a catalogue of household names, including Tommy Cooper, Roy Castle and Stratford Johns.

It proved so popular that it was remade for television in 1979.

In his twilight years he appeared in The Others, with Nicole Kidman, and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. His final film appearance was in the British coming-of-age comedy Son of Rambow.

Along with Milligan and the Monty Python team, Sykes was credited with bringing a more off-the-wall slant to mainstream British comedy.

On TV, Sykes and A... was followed by Sykes, which retained the same characters but saw the titular comedian move to 28 Sebastapol Terrace, an end-of-terrace house.

It was a piece of comic innocence, located in a sort of permanent 1950s, Ealing Studios world, with only the occasional contemporary reference to give away its 1970s setting.

The shows, co-starring Hattie Jaques as his "identical" (but very differently proportioned) twin, gave rise to some of television's most enduring comedy sequences.

Eric Sykes looks back on his life and career with BBC Manchester last year

They included a memorable five-minute monologue where Sykes got his <link> <caption>toe caught in a bath tap</caption> <url href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k66Omw186Gg" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

"I always say to young people, you can have the best script, be the funniest man, but if they don't laugh - you're not a comedian," he said in 2006.

Medical miracle

Sykes had been deaf since his early thirties. His trademark horn-rimmed spectacles were in fact a sophisticated hearing aid, enabling him to sense vibrations.

Doctors were surprised he could hear anything at all. But Sykes always attributed this medical mystery to the protective spirit of his dead mother, named Hattie like his famous co-star.

Sykes' trademark spectacles were actually a sophisticated hearing aid

"I still think she's here, I owe her so much - there have been miracles in my life," he told audiences at the Hay Festival six years ago.

Despite his deafness and later blindness, Sykes continued to perform on stage and screen well into his seventies.

He wielded a Zimmer frame like an offensive weapon to great comic effect in Alan Bennett's 1987 play, Kafka's Dick.

He also took the role of Professor Mollocks in the BBC's grandiose 2000 adaptation of Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast trilogy.

Sykes referred to himself as a solitary unit. His Canadian wife Edith and his four children were used to leaving him alone.

Yet he was never able to resist the lure of a private joke and called comedy "a calling".

"You don't decide to be a comedian," he said. "I don't ever stop.

"Even when I'm in the bath or shaving, my brain is going like an express train, thinking up funny things."

The modern era of comedy failed to entertain him - "why do they have to swear all the time?" he said - but he professed to enjoy Eddie Izzard's routines.

Izzard, Noel Fielding and Ross Noble are perhaps the most obvious inheritors of Sykes' humour.

His comic vision of the world helped to guide British humour in a markedly zanier direction and his influence is certain to endure.

- Published4 July 2012

- Published4 July 2012