Imagine the meeting that led to The Shard

- Published

- comments

A public platform offering panoramic views of London is due to open in February 2013

"What are the parameters for the project?" asks Renzo Piano the world famous architect.

"The sky's the limit," replies His Excellency Sheikh Hamad Bin Jassim Bin Jabor Al Thani, the prime minister of Qatar, and financial backer of the then proposed new property development at London Bridge.

Neither party speaks English as their first language - idioms can easily be misunderstood.

So a few years and a billion pounds or so later, the great architect delivers his monumental vision - a cloud-tickling skyscraper, a giant gleaming obelisk that emerges from London Bridge train station like a rocket about to take off. It dominates its surrounds like Gulliver in Lilliput.

To some the Shard is a new icon for London - a demonstration of the energy, urgency and modernity of the great city. To others it is a blot on the landscape - ugly, arrogant and inappropriate.

Renzo Piano, who is as charming and warm as a southern Italian village in the spring, is sanguine about the controversy his building has created. He says that when he watches people looking at The Shard he sees in their faces "amazement" and "wonder".

"Why the faceted form?" I ask

"Oh, that's simple," he says "it was the shape of the plot of land on which we could build."

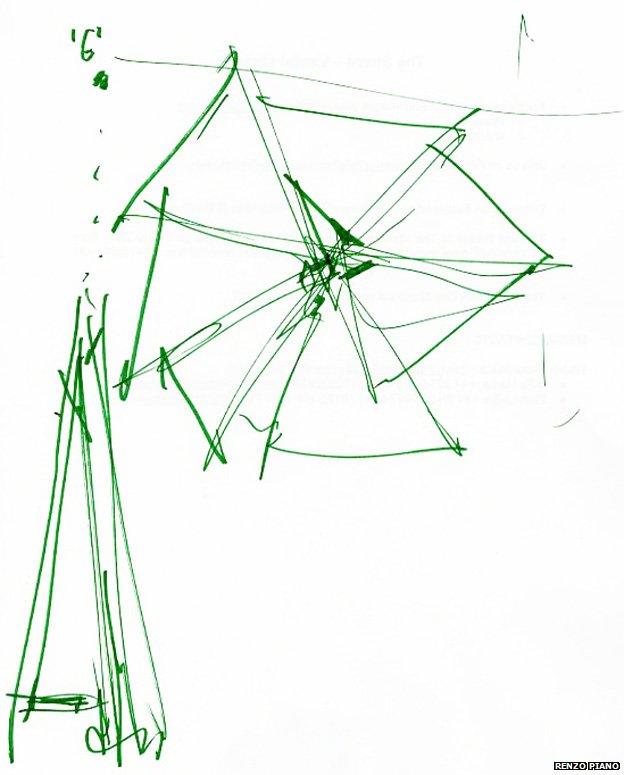

He then removes a green pen from his jacket and draws me an aerial sketch of The Shard. Next to it he draws a side-on view, making the point that although the building tapers at the top, the separate shards never touch. "They only flirt with each other," he says.

And then he draws a dotted line representing the imaginary moment - around a hundred meters higher - where the facets would meet, at which point he writes a capital "G".

"This," he says in his thick Italian accent "is the building's G-spot," and then chuckles delightedly, before adding with hope, "I think this design will be love-ed."

Ken Livingstone: The Shard 'will define London'

Not by everyone it won't. Those that have fought for and cherish what had been a protected view of Wren's St Paul's Cathedral from Hampstead Heath are appalled by what they see as The Shard's vulgar and unwanted appearance on the scene. For them it is like putting a wind-turbine in front of the Taj Mahal, or hanging florescent tubes from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Unesco in the past has threatened to put the Tower of London on its danger list because of concerns that its "visual integrity" could be being compromised by The Shard being built across the river. This week, Unesco's World Heritage Committee asked the UK government to protect the skyline in the area surrounding The Shard.

Everybody agrees about one thing though - The Shard is a very tall building. When you come out of London Bridge Station and look up it is like being at the foot of the north face of the Eiger - a sheer face of a white, glistening mass rises above you, climbing ever skyward like Jack's beanstalk.

Journalists attending a press conference on the 14th floor were surprised by the appearance of window cleaners

When you go inside and up to the 69th floor, which come February 2013 will be a publically accessible viewing gallery (if you pay the £24.95 charge for adults and £18.95 for children) and look down on London below, the great city is transformed into a toy town. The Gherkin, Tower of London and Canary Wharf are just parts of a million-piece jigsaw made up of buildings, parks, trees and infrastructure.

It becomes starkly apparent that London, unlike Paris, is not a city built around a grand architectural masterplan, but an organic creation formed over hundreds of years. It is both ugly and beautiful, a semi-formalised chaotic life-force.

Within this context I think that The Shard sits well. It is more elegant than arrogant - a considered piece of design by a master-craftsman.

It is in many ways a very hi-tech building, but not in all respects. It will still require a man with a sponge and a bucket of warm soapy water to clean the windows.

All 11,000 of them.