York Mystery Plays given new lease of life

- Published

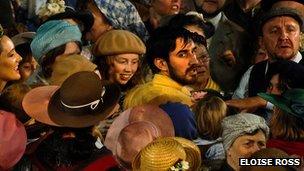

Some 500 people are part of the cast for York Mystery Plays

The York Mystery Plays, a theatrical tradition dating back to the 14th Century, have been resurrected in an epic production involving an Olivier Award-winning director and 1,700 enthusiastic local people.

It is with a mixture of pride and exhaustion that the two directors of the York Mystery Plays talk about the numbers of people taking part in their production, which retells Biblical stories on a near-Biblical scale.

There are two casts of 250 amateur performers, with bricklayers appearing alongside lawyers and children with their grandparents, who have between them been rehearsing for six nights a week for the past four months.

"One of our ambitions was to see how many people we could involve in this," says one of the directors, Paul Burbridge.

"Our working pattern has been very different from usual," adds Damian Cruden, the show's other director, with a sense of weary understatement.

Ferdinand Kingsley (centre), son of Sir Ben, plays both God and Jesus

The two sets of actors take turns - when one lot are on stage, the others are at home. That means the directors have been rehearsing two separate casts for the same three-hour show at the same time.

"Three hours of theatre is one thing - that's fairly normal," Burbridge continues. "But to get six hours of theatre ready in the first week has been quite a hurdle."

As well as the actors starring as angels and apostles, local sixth form woodwork students have made props, 80 women (and one man) have stitched the costumes and there is a 97-strong choir.

While the participants are mostly amateur (there are just two full-time actors), the production has been instilled with professional standards.

Cruden's day job is running York Theatre Royal. He won the Olivier Award for best entertainment show last year for The Railway Children, which featured a real steam train and was a hit in York and London.

Burbridge, meanwhile, is artistic director of the York-based Riding Lights Theatre Company. "Most of the productions I do normally are matchbox-sized compared with this," he says.

The play tells stories from the Bible, including that of Noah's Ark

"At times you feel like you're looking at a huge film set with masses of people on stage, all pulling in the same direction, creating big pictures."

For rehearsals, the play was prepared in quarters and slotted together in the final weeks. The stage, too, was split into different zones, resulting in intricate instructions like: "Red 37 enter at Yellow 2, grab a section of the Ark and go off at Red 9."

The amateur involvement has its origins in the medieval plays, when craftsmen's guilds would bring Bible stories to life on wagons in the city streets - the butchers depicted the death of Christ, the bakers did the Last Supper and candle-makers took care of the annunciation to the shepherds. They were plays staged by the people for the people.

Several other towns had their own mystery plays, but the manuscript from York is the most complete version to have survived and is now kept at the British Library.

It was this ancient text that was mined by Mike Kenny - who worked with Cruden on The Railway Children - when crafting the script for the 2012 revival.

He has boiled it down from 14 hours to just the three, rewriting some sections while sticking to the medieval text in others.

Graeme Hawley plays Satan after playing another villain, John Stape in Coronation Street

"He's done a great job so you still hear the medieval flavour, you still hear the rhythms of the medieval words," says Burbridge.

"It feels very real and contemporary and easy to listen to, but it's still got those alliterations and rhythms in the poetry that meant it was brilliant for being shouted in the streets."

The setting is updated, too, with much of the costume placing it in post-war Yorkshire - the Virgin Mary wears a headscarf and Joseph has a flat cap.

And the preparation has paid off. The thronging crowd scenes are a form of choreographed chaos, while the volume of bodies creates some striking spectacles, like when the umbrellas of a mob surrounding the Ark suddenly become a bobbing sea.

Ferdinand Kingsley, son of Sir Ben, plays God and Jesus, opposite Graeme Hawley, better known as serial killer John Stape in Coronation Street, who is now playing another bad guy - Satan.

The action takes place against the impressive backdrop of the ruins of St Mary's Abbey, which, like the original Mystery Plays themselves, was closed down during the Reformation of the 16th Century.

The grounds now host the biggest stage in northern England, Burbridge claims - although it is temporary - and the production has been billed as the largest outdoor theatre event in Britain this year (that may depend on whether you count the Olympic ceremonies, mind you).

Open air 'honesty'

After being quashed under the Reformation, the Mystery Plays returned to York for the Festival of Britain in 1951 - a 16-year-old Judi Dench played an angel that year and starred twice more in the 1950s.

The plays have been staged at irregular intervals at various venues ever since, but this is the biggest of the modern era and the first time they have been in the open air since 1988.

"They were stories that were told deliberately not in a church," Cruden explains. "They were for lay people to tell their own stories in their own way. I think there's an honesty about bringing it back into the open air."

And after several decades of on-off uncertainty, Cruden believes they have now set the template to allow this tradition to continue.

"I genuinely believe we've made something that should be able to be repeated again and again in the city every four years, and its legacy should be that it goes on and that it is genuinely owned by the people of this city."

The York Mystery Plays are on until 27 August. The production will be broadcast on digital arts channel The Space, external on Saturday 11 August.

- Published1 August 2012

- Published24 May 2012

- Published11 January 2012