Obituary: Sir Peter Maxwell Davies

- Published

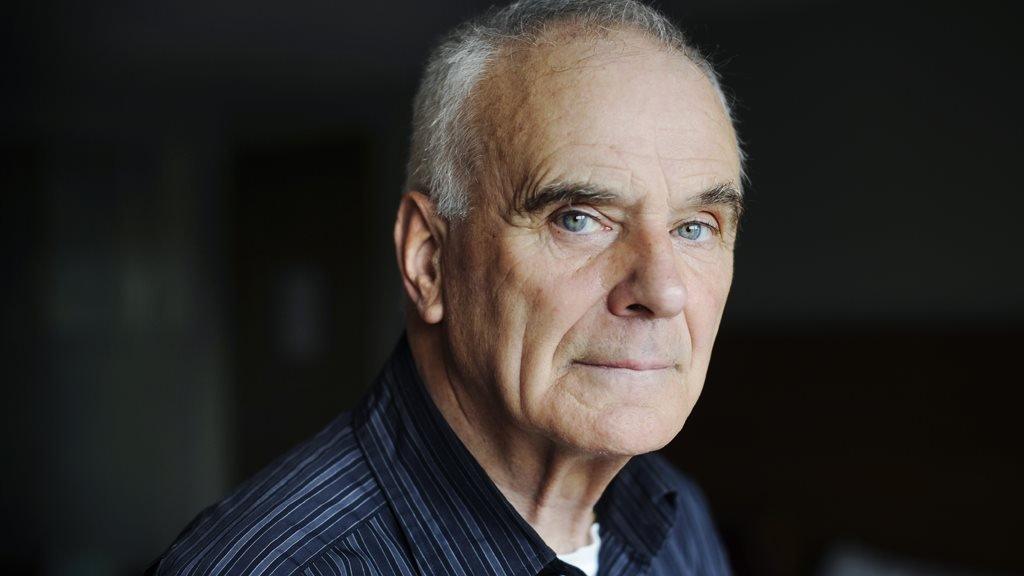

Sir Peter was 12 when his first composition was broadcast

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, celebrated for his prolific and often unpredictable compositions, has died aged 81.

The wild child of contemporary music, he delighted in pushing the boundaries to the extent that some of his earlier works were described as unplayable.

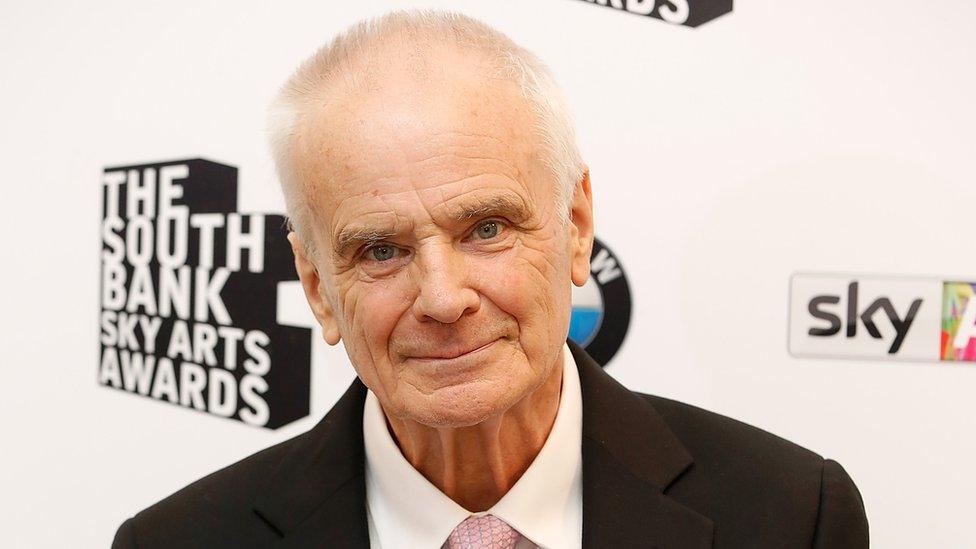

But he later became an establishment figure and was appointed as Master of the Queen's Music, external from 2004 to 2014 - the musical equivalent of poet laureate.

Maxwell Davies, later known simply as Max, was born in Salford on 8 Sep 1934, the son of a factory worker.

He became an authentic musical prodigy as a child. One of his earliest musical experiences was being taken to see a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Gondoliers when he was just four. Shortly afterwards he began taking piano lessons.

He was honoured with the role of Master of the Queen's Music

He was 12 when his first composition was broadcast by the BBC's Children's Hour. At Leigh Grammar School his interest in music wasn't encouraged, but Davies didn't let that hold him back.

He studied independently, taught himself A-level music and reputedly astonished his examiners by demonstrating that he had memorised not only Beethoven's violin concerto but the composer's symphonies as well.

Noisy and cacophonous

He duly won places at both the Royal Manchester College of Music and Manchester University, where he teamed up with three other future composers, Harrison Birtwistle, Elgar Howarth and Alexander Goehr.

They were known as "the Manchester School" and set out to frighten the horses. One of Maxwell Davies's earliest compositions, a String Quartet, was submitted to the Society for the Promotion of New Music but rejected as unplayable.

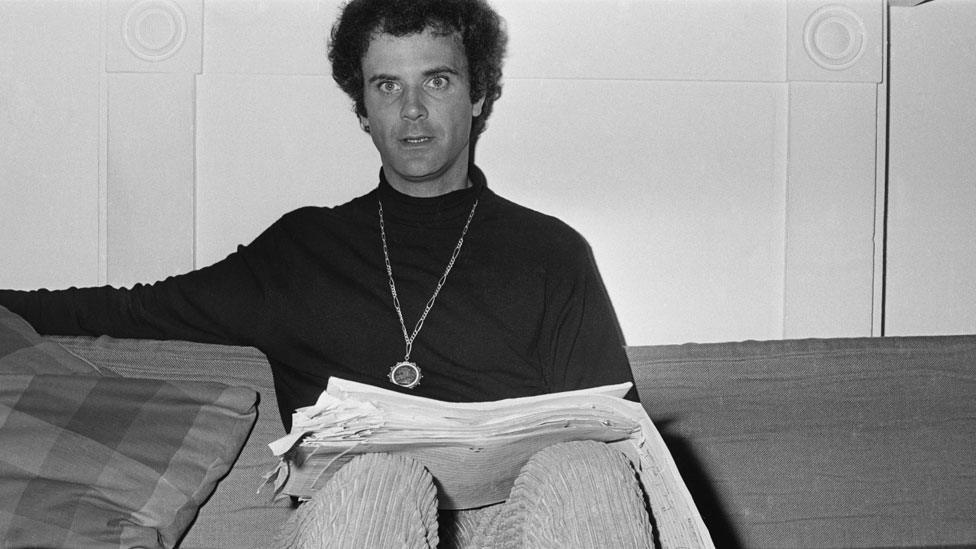

In due course he became immensely prolific as a composer, and rarely predictable. Many of his early works were lurid, noisy, brutal and cacophonous.

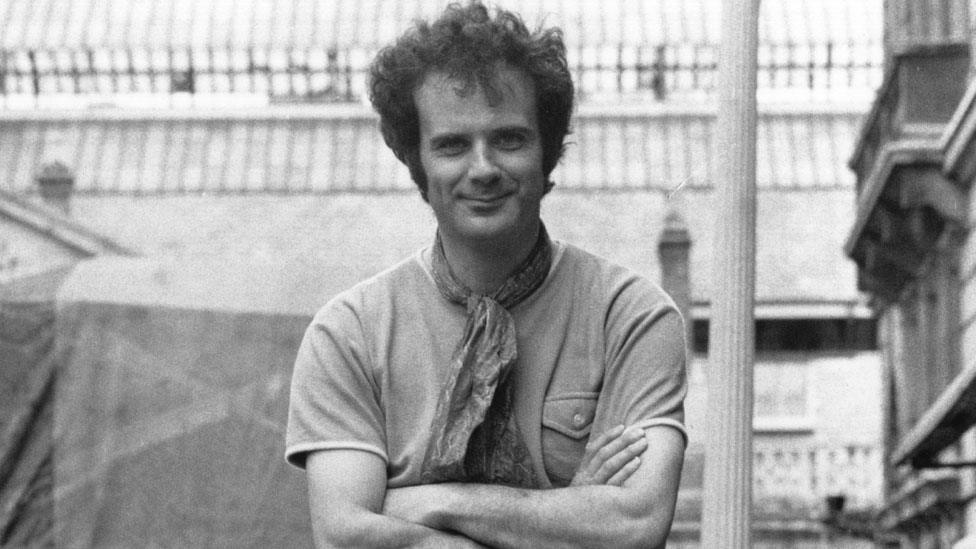

He was a determinedly Bohemian character

They were first performed by the Pierrot Players, later renamed Fires of London, an ensemble he founded with Harrison Birtwistle though the pair later fell out.

His music parodied and distorted medieval and Renaissance music or popular dance tunes, especially foxtrots.

In one work a soprano singer dressed in a red nun's habit screamed through a loudhailer. Another work featured a dancer and a solo cello.

Some people hated them and the composer found the criticism deeply hurtful. Performances of his work were sometimes punctuated by cries of "rubbish" and "shut up" from the audience.

Many walked out of the premiere of Worldes Blis at a BBC Prom in 1969 although Sir Peter had his revenge. Before the second performance he put it about, "mischievously" he said, that he had revised the work, though in fact he had not. The critics said how much better the revised version was.

Another controversial early work, Eight Songs for a Mad King, combined monologues spoken, shrieked and gabbled by the mad George III with fragments of Handel's Messiah.

Madness was a frequent theme in his early work, along with religion (or at least the religious music of the past) and the rejection of authority.

Yet these uncompromisingly modern works went hand in hand with something more approachable.

He also wrote many compositions for children

Between 1959 and 1962 Sir Peter was head of music at Cirencester Grammar School, and began writing the first of many works for children. Throughout his life he remained interested in music education and in composing works for the young.

Some time around 1970 he began to mellow. He made his first visit to Orkney, where he eventually went to live in 1971, first in a remote cliffside house on the island of Hoy and then on the even more remote island of Sanday. The islands had a profound effect on his music.

"There is a wonderful soundscape of sea and gull noises and the wind in the heather, which has always stayed with me," he once said. "I didn't consciously set out to mirror them but they got in there."

" I remember when I was writing the first symphony these extraordinary flute chords came through, and I didn't realise at the time but yes, those were the seagulls that I was hearing all the time."

He discovered the work of the Orcadian poet and novelist George Mackay Brown. Soon he was writing a series of symphonies, incorporating Scottish tunes in his works, setting Mackay Brown's poems to music and developing one of the author's novels into an opera.

He established long-term relationships as composer and conductor with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra and the Royal Philharmonic, writing many pieces with individual players in mind.

And while some of his work was as jagged as ever much of it became more conventionally melodic and so more popular.

This more approachable music included his scores for two films directed by Ken Russell, The Devils and The Boyfriend, in 1971, the Violin Concerto of 1985, and one of his best-known works, An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise, which features Scottish and Orcadian folk tunes and bagpipes and was written in 1985.

His most frequently-heard piece is probably Farewell to Stromness, a haunting lament for solo piano which is part of a musical "protest work", The Yellowcake Revue, first performed in 1980 when a uranium mine was planned in Orkney.

In all he wrote ten symphonies, several operas (including Taverner, Resurrection, The Lighthouse and The Doctor of Myddfai as well as The Martyrdom of St Magnus), two full-length ballets (Salome and Caroline Mathilde), 14 concertos and a cycle of string quartets.

'Unadventurous'

There were religious and semi-religious works like Ave Maris Stella and a setting of the Roman Catholic Mass for Westminster Cathedral, many of which use the medieval plainchant which had fascinated Sir Peter since his student days.

And there were several lighter works like Mavis in Las Vegas, inspired by his visit to the city and his detestation of the commercialisation of modern society.

In 1986 he was knighted and in 2004 he was appointed Master of the Queen's Music.

In 2008 his financial affairs made the news when his long standing business managers, Michael and Judith Arnold, were charged with stealing almost £450,000 from him over a period of more than 15 years.

Critics did not always like much of the music Peter Maxwell Davies wrote after 1970, decrying it as unadventurous and "safe". He claimed the criticism did not worry him.

"I have been criticised a lot for writing in different styles and different kinds of music," he said. "I've been called a prostitute. Fine. In that case, so was Mozart."

He used to say he felt driven to compose, however difficult his music sometimes was to listen to. "When you have a creative urge, you can't stop writing," he told the Guardian.

He was later appointed as Master of the Queen's Music

"I feel that I want to tell people how it is to be PMD, and I do hope my music reflects something of the spiritual values and helps people to understand their own musicality, their own spiritual development, and that it means something to people's spiritual lives.

"This is terribly important to me. I would hate not to have my pieces played. I would hate not to be able to communicate: it's a love of people, I think, as basic as that."

And to the question, did he know who he was? he replied: "Every piece of music that I write, whatever its style, is a step on the way to finding out. No, I don't know, but when I've written the next quartet or the next choral piece or whatever it is I'll be that much closer to finding out."

"And I hope in a way that I can never give you an answer in words, because I might stop writing music."

- Published14 March 2016