Johnny Marr on The Smiths and going solo

- Published

Johnny Marr returned to Manchester to write and record the album

Twenty-five years after leaving The Smiths, the band that inspired deeper devotion than any British group since The Beatles, guitarist Johnny Marr has found his own voice with his first solo album.

Since The Smiths split up in 1987, Johnny Marr has been trying to do one thing - to not sound like Johnny Marr.

Or rather trying not to sound like people expect Johnny Marr to sound - trying not to sound like he did in The Smiths.

"As successful as that was and as much as people loved it, when you're 24 or 25 you don't want to have a label stuck on your forehead and just be going round on a conveyor belt for the rest of your life, no matter how good that label is," he says.

After The Smiths, Marr hopped from group to group, his musical direction swerving sharply to defy expectations and prove that he could be more than Morrissey's old bandmate.

He played alongside the synths in Electronic with New Order's Bernard Sumner; scored a US number one album with alt-rockers Modest Mouse; worked on the Oscar-nominated soundtrack for the film Inception; was a member of Wakefield indie-rockers The Cribs; and contributed to the tumultuous pop of The The.

Now he is releasing his first solo album under his own name. And he resisted the urge to instantly discard any chord progressions or riffs that sounded too much like Johnny Marr.

"I've done plenty of that over the years," he says. "I was conscious of not repeating myself.

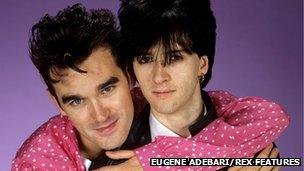

Morrissey and Marr will forever be idolised by many fans for their roles as the songwriters in The Smiths

"It was my prerogative to try and change peoples' perception of what I might be about and be a bit contrary if I needed to be. But this time out I was going to be OK with it. All the songs now start with my guitar, which I think is what people want."

He realised he no longer had to run away from his past when he was watching the punk pioneers Wire.

Wire were a massive influence on a legion of indie musicians, including Marr. As a fan, he did not want them to sound like anything but Wire.

"I want them to sound like Wire being as great as they can be," he says. "That was quite a profound revelation to me."

He could "just be me as well as I can possibly be", he realised. So the new album, titled The Messenger, does not sound like The Smiths, but nor does it hide the familiarly epic swells and sweeps of Marr's guitar.

He also sings, which he has done on occasion in the past. Unconcerned with recent guitar trends towards blog-baiting braininess or faux-primitive retro rock, his full-bodied indie would not have sounded out of place had he released it as his first post-Smiths project at the turn of the 1990s.

His lyrics encompass modern concerns, though, lamenting how commercialism and technology have taken over our lives. Word Starts Attack is about how people make and break friendships through social networks and texting. "How pixels are affecting relationships and what we think of an aid to communication is actually the opposite," he says.

I Want The Heartbeat is about a man who swaps his wife for an ECG machine. "He hooks himself up to it at night to get his heartbeat up and down. Could happen."

Marr says: "I've no interest in singing about my feelings and I've very little interest in other people singing about their feelings, if truth be told.

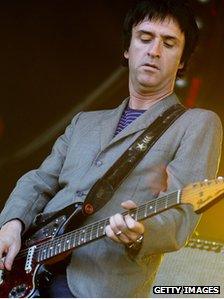

Marr spent three years as a member of The Cribs

"I like people who sing about their thoughts - whether that comes from observations or telling stories. As long as it isn't some earnest sentimental claptrap.

"A lot of stuff sounds like some bad self-help book masquerading as ideology. There's some collective 'together we're going to look up to the heavens and overcome this incredible adversity with our souls'. What adversity are we talking about here?"

The target of his ire is "music that fills stadiums that people really want to buy in supermarkets".

"When the record was finished, I realised I sang about the way modern life is for me, but I tried to do it in a way that at least people can be entertained by if not entirely relate to," he adds. "Obviously I hope they can relate to it. Or just find it funny.

"As long as it's not 'I'm gonna fix you.'" Yes, Coldplay, he is talking to you. "I miss people singing weird stuff from the brain. It's all a little bit too earnest for me now. Karaoke culture."

Marr clearly puts Morrissey's lyrics for The Smiths into the "weird stuff from the brain" category rather than the "earnest sentimental claptrap" category.

"They were certainly fascinating and unique," the guitarist reflects. "I don't think there was ever anything soppy in there and if there was I would have backed him up like I backed up everything he did and he backed up everything that I did.

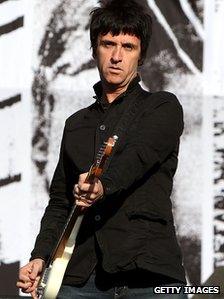

Marr will play his new material on tour in March

"I don't think we did do anything that we didn't love 100 per cent, even if it was just at the time. As songwriters, we entirely backed each other up to the max."

To write this album, the guitarist returned to Manchester after five years in Portland, Oregon, because the record "needed to sound like me being where I'm from", Marr says.

But despite making peace with the sound of his former self, Marr firmly rejects the suggestion that his return to Manchester was part of any kind of nostalgia trip.

"I'm sort of resolutely against nostalgia," he says. "There's something mawkish about it to me and it gets in the way of moving forward. I'm sure there's some creative use in it for some other people but not for me."

Nostalgia is a force that Marr has got used to pushing against. Hopeful reports of The Smiths' imminent reformation now come along with reliable regularity. But they have always been quickly shot down by Morrissey and Marr.

I tell him I am now going to ask the question that all journalists leave to the end of their interviews. He glances knowingly at his plugger.

Has a reunion ever been on the cards? "Er… no. No," Marr replies wearily. Will it be? Marr's interest in this interview has suddenly crashed. "Er… don't know. I don't know. I don't have an answer to that question."

That answer looks evasive in black and white, but at the time I simply take it as a sign of his antipathy toward the question.

The message from The Messenger is that he is comfortable with his past, but still not likely to repeat it.