Man Booker Prize: Size does matter

- Published

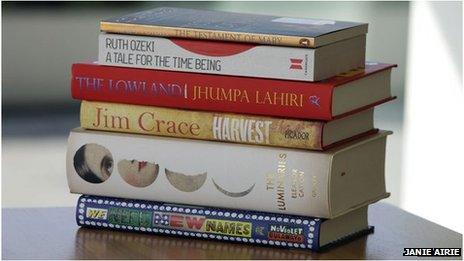

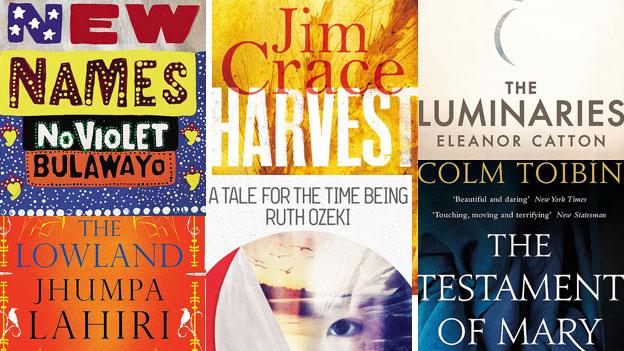

Colm Toibin's The Testament of Mary (top) is dwarfed by its Man Booker rivals

The Turner Prize cherishes its role as the naughtiest award on the block. It delights in pleasing Hoxton and provoking Tunbridge Wells.

If there is not at least one furious article rhetorically asking "call that art?!" the general feeling among its promoters is one of failure. Its stated raison d'etre is to provoke a debate about contemporary British art.

Not so the straight-laced, middle-aged, literary-minded Man Booker Prize.

Syntax and substance are what it is about, not courting controversy. And yet it is the sober, sensible Man Booker that has been the awards season's bad boy of late: causing offence one year, challenging assumptions the next.

Two years ago the literati were appalled that the esteemed prize should be awarded on the grounds of "readability".

Last year it was Will Self's lightly punctuated, temporally fragmented, densely written modernist tome Umbrella that had emotions running high and the Pinot Grigio running out at book groups across the country.

This year the Man Booker has unwittingly out-Turner Prized the Turner Prize by shortlisting a work (Colm Toibin's 101-page The Testament of Mary) that has led to some ask rhetorically, "call that a book?!"

It is proof that even in the high-minded world of literary fiction, there are those who think size matters.

Not Ernest Hemingway, if legend is to be believed. Challenged to write the shortest of novels, the master of terse prose is said to have come up with this: "For sale. Baby shoes, never worn."

Would that pass the Man Booker's judging criteria, which states that for a work to qualify on literary and artistic grounds it must be "unified and substantial"?

(Substantial in the context, one assumes given the selection of The Testament of Mary, means formally and intellectually, not physical size or word count.)

Is there a word count at which a short story becomes a novella and a novella becomes a novel?

Penelope Fitzgerald won the prize in 1979 with Offshore, a 132-page story. Julian Barnes wrote just 28 pages more to win in 2011 with The Sense of an Ending. What was the page count when they crossed the invisible line between genres?

Frankly, I think the shorter the better. Not that a book ought to be short per se, but it should be as short as possible. And if that's 101 pages, then fine. Far more preferable to the current trend for over-written, under-edited six and seven-hundred page mega-books.

How many of these grandiose publications are worth the time and trouble invested by author, publisher and reader? Not a lot in my experience. Seven hundred pages for £9.99 might seem like value for money, but only if you place absolutely no value on your time. For a reader, expansive is expensive.

Paper rationing after the war was the reason books were generally shorter in the late 1940s and '50s. Maybe environmental concerns should be a reason for looking to cut back pagination today.

It strikes me that the beleaguered editor in the publishing house - a largely unsung hero in the creation of great books - needs such a reason to provide the necessary authority to persuade a loquacious, powerful star author on whom the company depends to just cut it out.

- Published11 September 2013

- Published10 September 2013

- Published23 July 2013

- Published17 December 2012