The real story behind the Scottsboro Boys musical

- Published

The Scottboro Boys, which opens at The Young Vic tomorrow, is a musical based on the true story of a group of black teenagers wrongly accused of rape. Their case became a milestone in the history of US civil rights - but the daughter of one of the real Scottsboro Boys mainly recalls her father's private suffering.

Professor Dan Carter first published his book on the Scottsboro Boys trials as long ago as 1969, so he's become adept at summarising how the complex legal and human saga began.

"One day in the spring of 1931 a group of hobos, black and white, were travelling on a train in north Alabama. A fight broke out and the train had to be stopped near the town of Scottsboro. Nine young black men - the youngest was 13 - were arrested.

"But then the Deputy Sheriff realised two of the white hobos were in fact women. The young women worried they might be accused of prostitution, so they accused the black boys of having raped them.

"I think anyone today who studied the evidence would conclude no rapes occurred. In any case, what happened after March 1931 took on an astonishing life of its own. What happened on the train was just a part of the story."

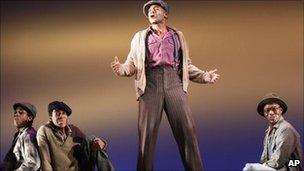

The Scottsboro Boys was nominated for 12 Tony awards in 2011 when it was on Broadway - many of the cast are in the London production.

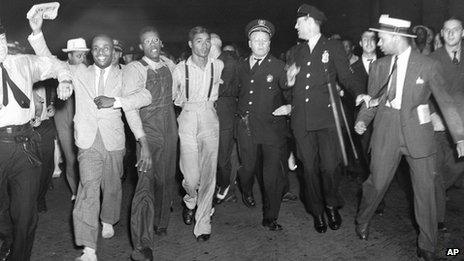

For the rest of the 1930s, the Scottsboro Boys (as they soon became known) were front page news in America.

At the first of numerous trials, eight of the nine received death sentences and some of them spent long periods on Death Row. That ultimately no one was executed was in part the doing of the Communist Party USA.

The communists paid for the services of celebrated attorney Samuel Leibowitz to defend the Boys. The involvement of political radicals infuriated Alabamans - some of whom didn't much enjoy being lectured by a Jewish lawyer from New York.

But Dan Carter says the party's money and organising abilities proved crucial. "Without them, some of the Scottsboro Boys would surely have gone to the electric chair."

At times it seemed the Scottsboro Boys had become pawns in a protracted face-off between liberal America and the conservative (and still segregated) south.

But over the years the authorities in Alabama lost faith in the evidence against the Boys, who were now men. And perhaps Alabama decided the whole thing was more trouble than it was worth, with repeated appeals to the Supreme Court in Washington.

The last of the nine men walked free in 1950, almost two decades after the original charges.

Fresh start

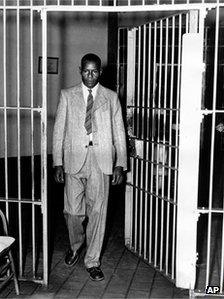

Clarence Norris had been paroled in 1946. Seeking a fresh start he assumed his brother's identity and moved north to New York City. He married and took jobs as a warehouseman and in sanitation.

In 1946 Clarence Norris was paroled from Kilby prison after serving nine years of a life sentence.

His daughter Deborah Webster remembers with absolute clarity the day her father told her and her sister about his earlier life.

"I was around 14 or 15 and he was in his late 50s. I was shocked at what he told me. Shocked.

"As a teenager in New York I had never heard of the Scottsboro Boys so he had to explain the whole story. But the fact my father spent years in jail for something he didn't do hurt me deeply."

"I could see the hurt in his eyes too - and I will never forget it. The pain never left him. It wasn't just his freedom that was taken from him. He didn't have his family anymore and he'd had to assume someone else's identity. Who wouldn't be pained at that?

But Deborah thinks ultimately the revelation helped her understand her father better.

"My father was very distant. There were times he came off a little too hard. I used to always feel he had no heart at all. But, in later years, I could connect and understand where all that was coming from. It was from a real dark place."

"He wasn't educated, due to his situation when he was a young man. So I would get home from school and he would ask me to read his mail to him.

"I thought he was checking up on my schooling but then I realised he didn't know how to read. With all the things he went through we had modest means and we struggled a lot. We're still struggling.

"But my father never spoke of any hate. He never taught us to be prejudiced and I honour him for that. That had to take a special kind of human being to not have that in his heart after all he'd been through."

Full pardon

In 1976, Alabama governor George Wallace agreed to a full pardon for Clarence Norris. Speaking for the TV cameras, after years of lying low, Clarence Norris said he held hate for no one. He wished only that 'these other eight Boys' were around.

Deborah recalls that the pardon brought her father great happiness. "He even learned how to read. I took great pride in that, to see him overcome a lot of the barriers he had to face. I will always remain proud of my father and I'm very honoured to be his daughter."

Deborah Norris Webster and her son saw The Scottsboro Boys on Broadway and met actor Rodney Hicks, who played Clarence Norris.

Three years ago Deborah and her son Harsan were invited to the original New York production of The Scottsboro Boys, external. The story might not seem a natural fit for a musical - so had she hesitated?

"I was in two minds at first, though I was thrilled that all these years later people are still interested in the Scottsboro Boys. But the way the play was brought across it took a lot of the harshness out of the actual story. So I could sit there and enjoy it. Music lightens the heart."

Some see the Scottsboro trials as a precursor of the civil rights movement of later years. Dan Carter says one effect was an important Supreme Court judgement which made it illegal to exclude black jurors in a trial.

Professor Carter has been at the forefront of those seeking a full pardon for all nine Scottsboro Boys. It's thought the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles may decide before the end of the year.

"I'm pretty optimistic," says Professor Carter. "Of course everyone concerned is dead or presumed dead. But even if it's only a symbol of reconciliation and respect it's one many people would welcome profoundly."

The Scottsboro Boys opens at the Young Vic 18 October.

Listen to Vincent Dowd's Witness on the Scottsboro Boys via BBC iPlayer Radio or download the programme from the BBC World Service podcast archive.

- Published9 September 2013

- Published17 May 2011