The Pajama Game musical woos new breed of investor

- Published

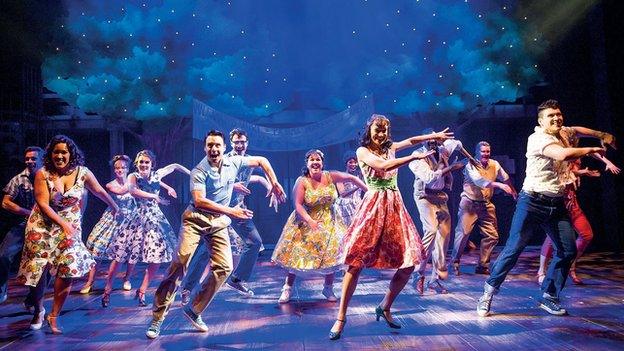

The Pajama Game has transferred to the West End from Chichester Festival Theatre

The Pajama Game opens in London's West End this week having raised more than £200,000 through a crowdfunding scheme. Why is commercial theatre chasing a new breed of investor?

"Theatre investors are normally private individuals who would be coming into a show for anything from £5,000 upwards," says Gavin Kalin, co-producer of classic musical The Pajama Game.

"To some that's not a lot. To others, it's a hell of a lot."

After a hit run at Chichester Festival Theatre, Kalin and co-producer John Brant decided to turn to small investors to help raise the cash to transfer the production to the West End.

Using the equity crowdfunding site Seedrs, external, they allowed people to invest anything from £10 to £25,000.

That was in February - £40,000 was raised in the first 24 hours.

The target of £200,000 - 14% of the capital costs of the project - was exceeded in April, with money from 218 individuals.

"It's fantastic to not only have them as investors but also as advocates coming to see the show, telling people about it," says Kalin.

Brant adds: "Theatre is a medium for the general public. Why shouldn't theatre investment be the same?"

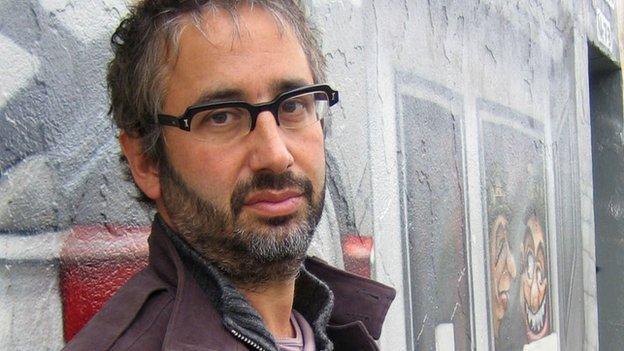

Comedian David Baddiel's project Infidel - The Musical! sourced £55,000 via Kickstarter

Crowdfunding is not new to the theatre world. Last year, new musical American Psycho at the Almeida Theatre raised more than $150,000, external (£89,000) from 1,421 backers.

Pledges started from $1. Two people gave $10,000 (£5,900) apiece.

Last month, comedian David Baddiel's project Infidel - The Musical! sourced £55,000 via Kickstarter, external.

Investors is such schemes might earn themselves free tickets, a chance to meet the cast or attend first night parties - even a production credit - depending on how much they give.

But what they don't see is a financial return.

Profit making

By contrast, The Pajama Game is the first West End show to have cash from an arrangement that could give investors - even those giving just £10 - a share of potential profits.

"We offered investors the same investment terms that a non-Seedrs investor receives who has put in tens of thousands of pounds," says Kalin.

He explains how it works: when the show has recouped its capital and running costs the original investment is returned. After that profits are split 60% to investors and 40% to the producers.

"We have to always put the caveat there are no guarantees of any of this. The show has to sell enough tickets to make sure that happens," he adds.

Kalin and Brant aren't the only commercial producers to have used this profit-for-all model.

Jamie Hendry raised more than £1m earlier this year for the forthcoming new musical The Wind in the Willows, external, an adaptation of Kenneth Grahame's classic novel by Julian Fellowes.

More than 400 people joined the scheme with individual investments of £1,000, £2,500 or £5,000.

After the target was reached in February, Hendry said: "I was interested to learn that the vast majority of investors had not only never invested in the theatre before, but didn't even realise it was an option."

As with The Pajama Game, each investor will get a share of potential profits. The show has yet to announce its start date.

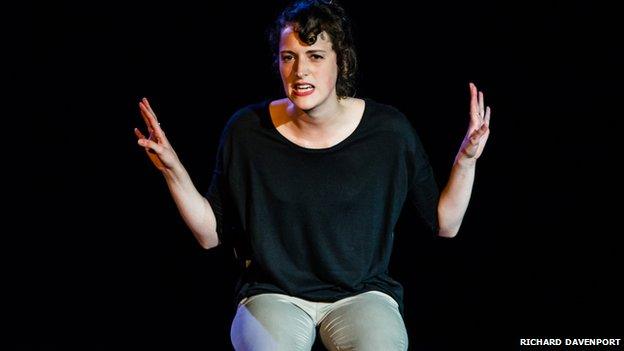

Crowdfunding campaigns can have long-term effects for smaller shows such as DryWrite's Fleabag.

The one-woman show, written and performed by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, sourced almost £4,000 via Kickstarter, external to help fund its world premiere run at the Edinburgh Festival last summer.

"We thought it was too good to be true," says Waller-Bridge, who didn't even have a finished script when the money started to come in. "We watched other people's videos and we thought this is where we should be."

"We asked for £3,000 and got it in about two days," recalls director Vicky Jones. "The scheme values a tenner as much as it does £500."

Fleabag, written and performed by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, was nominated for an Olivier award

The show's success in Scotland helped fund a run at London's Soho Theatre in the autumn of 2013 and it has just returned to the same venue.

Along the way it has picked up several awards - and an Olivier nomination.

Both Waller-Bridge and Jones say they will "definitely" use Kickstarter again for a future project.

But theatre industry expert Terri Paddock points out crowdfunding does not work for every kind of show.

"It's the same type of risk that any producer has when putting together the project to begin with," she says.

"Crowdfunders are the audience, so you have to catch their imagination even earlier and more provocatively for them to put their hand in their pockets before they even buy a ticket.

"Never forget, that only three in 10 shows recoup on average. So it is quite risky.

"Where the money comes from doesn't change that though - arguably in the age of social media, the more stakeholders you have out there championing a show, the greater the reach."

'Democratises investment process'

Both Kalin and Brant say their "old school" big-money investors in The Pajama Game have been supportive of the crowdfunding scheme.

"There's been no grumbling at all. They all see it's a direction that many an industry is going in," says Brant.

So is this a bright new dawn for commercial producers? "It's a difficult industry, let's not sugar coat that," says Kalin.

"Every time you put a new show on it's like a new start up.

"We did it in the West End first and it's been successful, so I can't imagine that other producers aren't looking at it thinking that it's a really good way to raise 10% or 20% of the my capitalisation for their next show."

The Pajama Game's producers are keen to get into bed again with small investors.

"Why wouldn't we?" says Kalin. "It democratises the investment process, and it's good from a PR point of view. It allows the general public to become part of the theatre industry. That's so important right now."

Whether those crowdfunders see a return on their investment is something that other West End producers will be watching very closely over the weeks ahead.

The Pajama Game, directed by Richard Eyre, runs at the Shaftesbury Theatre until 13 September. Fleabag is at the Soho Theatre until 25 May.

- Published23 August 2012

- Published9 December 2011