Writers' notebooks: 'A junkyard of the mind'

- Published

Lawrence Norfolk's notebooks have evolved over time

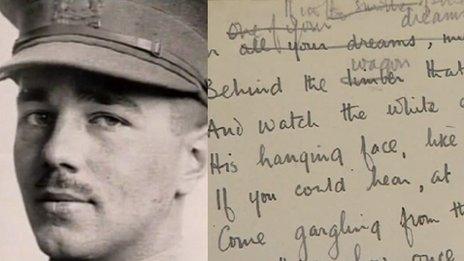

As the British Library puts huge swathes of writers' and poets' personal archives online on their Discovering Literature, external site, including papers from Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens, novelist Lawrence Norfolk looks at the significance of the notebook to a writer.

The first page of my notebook holds a column of place names, some cuneiform letters taken from a tomb in the British Library and a collection of oddly-named English meadow flowers (wet-the-bed, yellow rattle, adder's tongue fern).

Turning the page, I find a list of books with library numbers from the British or London libraries, then caravan names (Sprite, Lunar, the Senator range) then some players of un-credited guitar solos: Eric Clapton on When my Guitar Gently Weeps, Brian May on a Black Sabbath track, a few others. Turning to the back, I write the word Letter.

I am travelling on a German train between Hannover and Osnabruck. Letter is the name of the station through which I have just passed.

The next is Haste. I write that too. What, I wonder, if the name of every station on the line turns out to be cognate with English words? What if the stations form a sentence? A paragraph?

Unfortunately, the next station is Gummer.

Mind junkyard

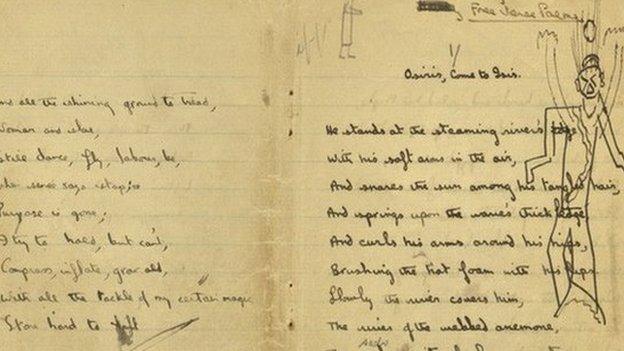

A writer's notebook is a junkyard; a junkyard of the mind. In this repository of failed attempts, different inks speak of widely-spaced times and places, the diverse scrawls of varying levels of calligraphic awkwardness, lack of firm writing-surfaces, different modes of transportation.

All the places a good idea might blossom into something bigger and better.

No writer should believe in serendipity. All of us do.

Thomas Hardy kept 'literary notebooks', a 'Poetical Matter' notebook and a 'Studies, Specimens, etc' notebook. But the richest to my mind is one with the bare title, 'Facts'.

Here Hardy and his first wife, Emma, noted down incidents culled from local newspapers. One entry (barely three lines long) is headed Sale of Wife. Out of that fragment came The Mayor of Casterbridge.

Of course, almost everything else in the Facts notebook resulted in nothing at all. A notebook is an act of triage on the world outside. A little 'fact' goes a long way in fiction.

My German train slides past the backs of factories, blocks of flats and houses. Heading out into the countryside, I see two imposing hills.

Halfway up the nearest slope, a large statue stands within a structure that resembles an ancient Greek bandstand.

The statue will be some comically-obscure German official. The Elector-Palatinate of Gummer perhaps.

I note down the nearest station and make a bad ink-sketch of the bandstand. Then I arrive at Osnabruck.

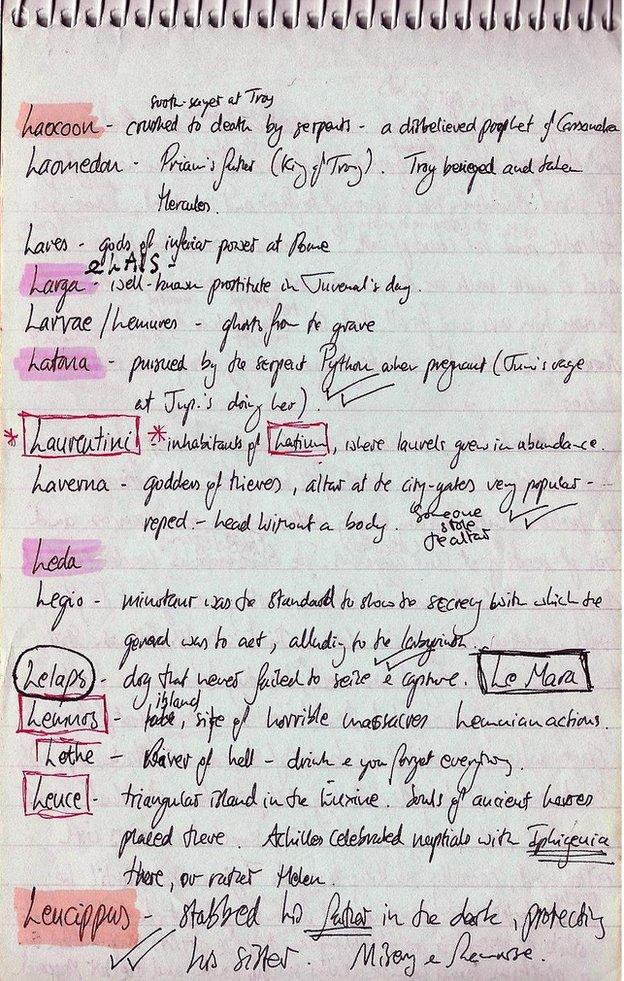

The L page in one notebook annotated with colours and stars and ticks

Franz Kafka wrote in quarto-sized notebooks before trading down to octavo near the end of his life. Jean-Jacques Rousseau made notes on playing cards during walks that were later written up as his Reveries of a Solitary Walker.

I make notes on library slips, envelopes, junk mail, whatever's lying about. All these scraps end up shoved into notebooks.

I'm not particular about brands (the moleskin is high-end for me), only size, specifically whether they require a pocket or a bag, and how much I can get on one page.

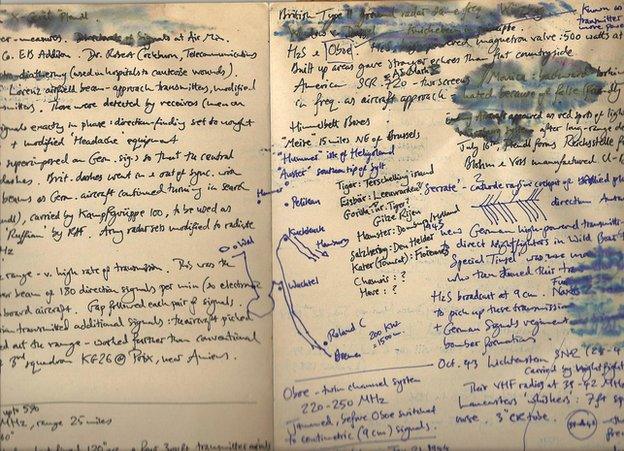

The research for my book Lempriere's Dictionary was written in spiral-bound shorthand notepads, filled with notes on classical mythology, late eighteenth century newspaper reports, clothes descriptions, weather reports, ship catalogues, details of the siege of La Rochelle and early automata.

Later I switched to larger format books. These were between A4 and A3 size and the obvious drawback was portability but I lugged these volumes back and forth to libraries nevertheless.

At first I simply jotted stuff down as before but gradually I noticed that my note-taking had changed. With this new expanse of space, certain pages would take on their own momentum.

Train of thought

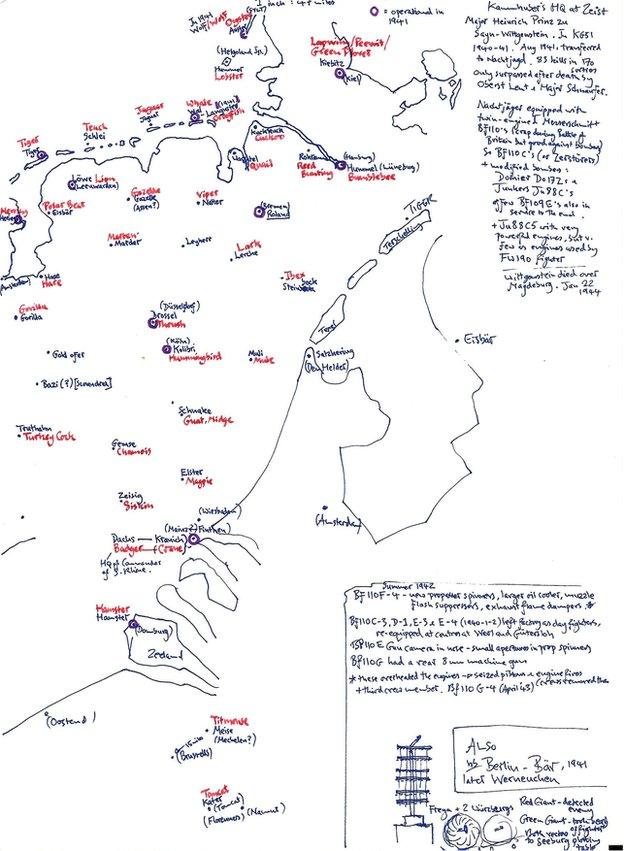

A map of Himmelbett German radar stations began life as research for a scene in which a German World War II night-fighter pilot flies his newly-delivered Messerschmitt Bf-109 E-series (an Emil in the slang of the time) down the coast of Holland, accidentally setting off alerts among the different Himmelbett radar stations which monitored the coast against English bombers.

These stations divided the airspace into sectors of operation (or boxes) which were code-named for different animals and fish. I had in mind a German fighter pilot flying through an airborne zoo.

I collected these box code-names from the memoirs of German night-fighter pilots who would routinely refer to flying and making contact in Lobster or Oyster or Polar Bear.

Then I collated these references on a map to discover which box the particular creature referred to.

I never wrote the scene. But long after I'd abandoned the idea, I was still collecting Himmelbett box code-names and fitting them into my plan.

A map of Himmelbett German radar stations provided inspiration

Similar projects (in the same book) include a table (eventually, several tables) of the sound shifts which mark stages in the development of Middle High German, plans for a radio transmitter using only technology available in the fourth century AD and a catalogue (still being compiled) of books which once existed but now have vanished.

No sensible writer intends projects like these. At the same time, no writer using a notebook can guard fully against them. They just happen.

A notebook accumulates its value slowly, line by line and page by page. Like Hardy's Wife for Sale, who knows what will prove a dead-end and what the inspiration or material for a book?

A detail jotted down in two minutes might occupy you for the next three years. The protagonist of your next book might turn out to be the Elector-Palatinate of Gummer.

A full notebook potentially contains the rest of your writing life. Or nothing of value at all. It is transitional. Work passes through it on the way to becoming something else.

I used the caravan list in a short story about two lovers not quite falling apart during an impromptu visit to Little Rollright (the easternmost stone circle in Britain, also from the notebook). The un-credited guitar soloists went into that story too.

Of the remainder, I don't know. Not the railway station names anyway. And I never found the identity of the statue, the Elector-Palatinate or whoever he was. I got off at Osnabruck. I left the notebook on the train.

Lawrence Norfolk will be talking to writers including AS Byatt, David Mitchell, and Wendy Cope on BBC Radio 3's Free Thinking on 21 May at 2200 BST.

- Published26 April 2014

- Published25 April 2014

- Published14 April 2014

- Published18 March 2014