Dazzle Ships and the art of confusion

- Published

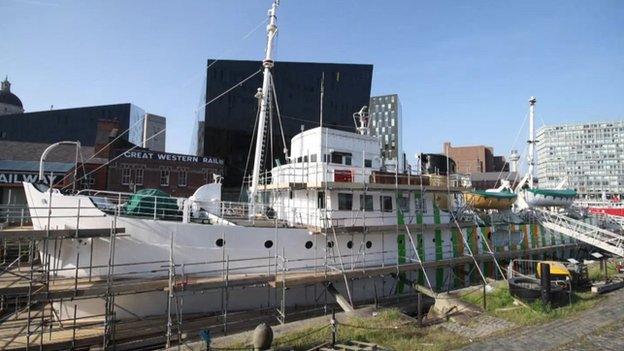

A pilot boat, conserved by the Merseyside Maritime Museum, has received a fresh lick of paint. Its striking new design reveals a fascinating history of the art of confusion in warfare.

The Edmund Gardener is a retired 760-tonne Mersey Pilot ship. This is what it looked like three weeks ago…

And this is what it looks like now…

Snazzy.

A Venezuelan artist called Carlos Cruz-Diez designed its fancy new coat. He was commissioned by the Liverpool Biennial and 14-18 NOW - a pop-up arts outfit that is planning a series of commissions to mark the centenary of World War One. This is its first.

Carlos has turned the plain old Edmund Gardener into a "dazzle ship": a piece of optical art intended to bemuse.

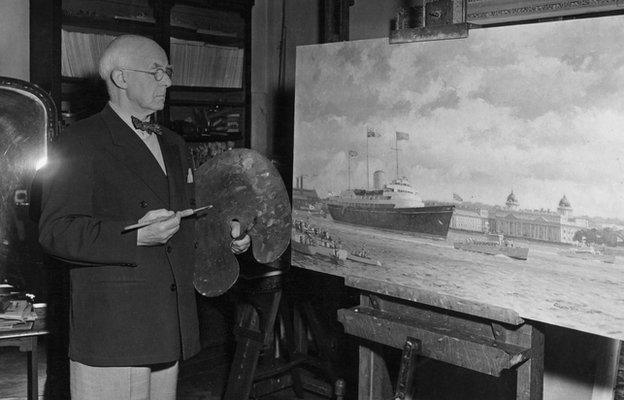

The dazzle idea is not his, it was the brainchild of a rather conventional British marine artist called Norman Wilkinson (1878-1971).

Here's a picture of him standing proudly by one of his paintings.

There was nothing conventional about Wilkinson's dazzle ship concept. It was an eccentric idea inspired by the most cutting edge contemporary art of the time; namely Cubism, Futurism and Vorticism.

The notion came to him in 1917 when serving as a Royal Navy volunteer, during which time he witnessed the siege that German U-boats had Britain's merchant ships under. It was a fierce blockade that was successfully cutting off much-needed supplies from abroad. Something had to be done.

Wilkinson realised there was no camouflage that could conceal a ship - that had already been tried and failed - but he thought there might be one that could confuse the enemy. One that would buy a captain on a merchant ship enough time to identify a marauding U-boat and sink it before it sank him.

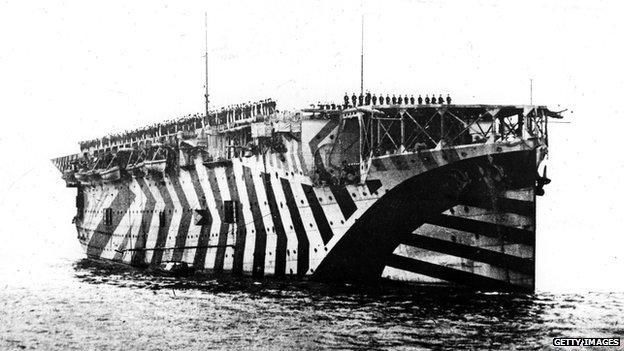

How about, he thought, a camouflage that didn't attempt invisibility, but one that did quite the opposite? One so eye-catching it would dazzle and disorientate. The Navy gave him the green light, and this is what he came up with.

The contrasting stripes, bold curves, and vivid spirals were devised to make it difficult for a U-boat commander to gauge the ship's direction of travel and speed, causing him to either dither long enough to give away his position, or miss his target when firing a torpedo.

The Navy approved of the idea and asked Wilkinson to go into mass production, which he did with the help of student artists based at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

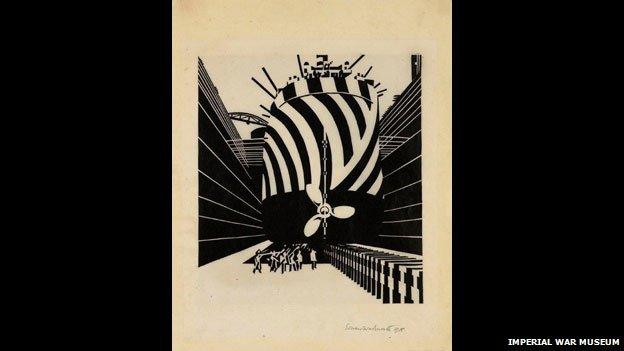

As luck would have it, the Vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth had joined the Navy and was available to go to Liverpool and oversee many of the dazzle designs painted onto the ships. In 1918 he was commissioned to make this artwork: Dazzle Camouflage, Ship in Dry Dock.

When Picasso caught sight of the dazzle camouflage he immediately took credit for the idea, saying it was inspired by his Cubist paintings. Mother Nature might argue that she got there first with her op-art design for zebras. Either way, these eccentric floating artworks are now a colourful part of Britain's maritime history - although there was never any concrete evidence they actually worked. How could there be? Each one of the 2,000 or so ships that were "dazzled" had a unique design.

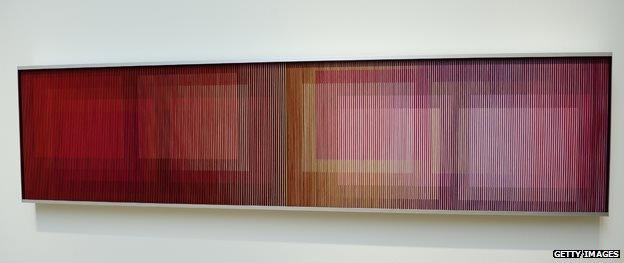

When the 90-year old Carlos Cruz-Diez got the call asking him to create a design for the Edmund Gardener, he'd not heard of the dazzle ships. Which is a little surprising, given that he has spent his entire career researching and pushing the possibilities of optical and kinetic art. Here's a piece called Physichromie No 321-A, which he made in the mid-60s.

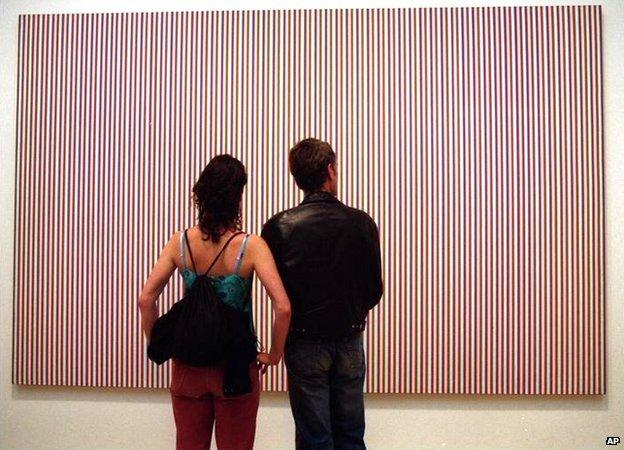

Cruz-Diez was not the first choice for the commission. The artist that the organisers really wanted for the paint job was Bridget Riley. She would have been very good. The British artist spent her life making the most exceptional pieces of optical art, like this…

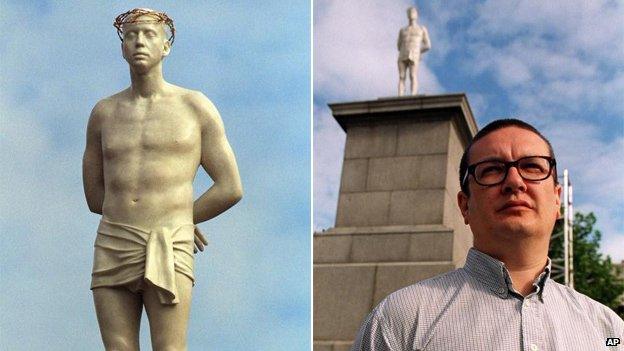

But she was unable to take on the commission. Carlos wasn't the second choice either. That position belongs to Mark Wallinger, who is perhaps best known for Ecce Homme (1999), his Fourth Plinth sculpture in London's Trafalgar Square.

The Turner Prize-winning artist said "yes" at first, and then said "no". So, in stepped signor Cruz-Diez at the eleventh hour.

He was inspired, he said, by the original story of the dazzle ships, which he described as "awesome", because they were "something that was made to be beautiful and promote something other than death."

The Edmund Gardner is situated in a dry dock adjacent to Liverpool's Albert Dock and can be seen now.