How the colour-blind see art with different eyes

- Published

A riot of red: Edgar Degas's Combing the Hair (La Coiffure) is part of the Making Colour exhibition

In its latest exhibition, the National Gallery examines how generations of painters have created and used colour. But how do people who are "colour-blind" view art?

Visitors to the Making Colour, external exhibition, which opened in London this week, can feast their eyes on the rich tones of lapis lazuli, vermilion and verdigris.

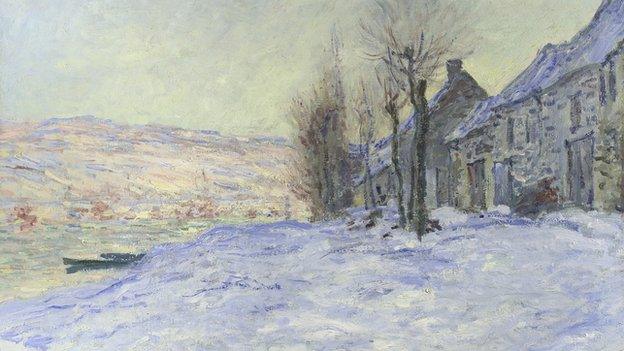

In the National Gallery's colour-themed show, the paintings include a blue room containing Claude Monet's Lavacourt under Snow (1878-81) and - in the red room - Edgar Degas's Combing the Hair (La Coiffure) from 1896.

But to anyone who has a colour vision deficiency, commonly known as colour blindness, the bold reds that dominate the Degas work may look very different.

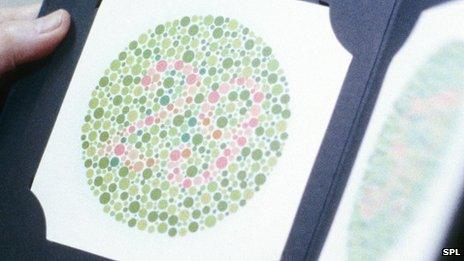

The subject of colour blindness is tackled in an interactive part of the exhibition devoted to the science behind colour vision.

Claude Monet's Lavacourt under Snow (1878-81) is also part of the exhibition

The retina at the back of eye contains light sensors called cones. The three cone types - red, green and blue - are stimulated by different wavelengths of light.

Most colour-blind people have three types of cone, but they are sensitive to a different part of the spectrum.

By Tim Masters - who has first hand experience of colour blindness

The earliest sign that I was colour-blind was, according to my parents, when I drew a picture of Doctor Who's Tardis - and made it shocking pink.

When I tell people I'm colour-blind some assume I see the world in black and white.

That's far from the truth. I can see rainbows. I just don't see them in the same way as most people.

Walking around the Making Colour exhibition, I was dazzled by the ultramarine blues and daffodil yellows.

But was that a big patch of green in Degas's La Coiffure? The sign said it was red, but my eyes said something different.

Apart from a fashion faux pas involving some burgundy trousers, I've never found my colour blindness to be much of a problem. It's never detracted from my enjoyment of art.

Just don't ask me for sartorial advice - or to repaint a police box.

Joseph Padfield, a conservation scientist at the National Gallery, is one of the experts who devised the interactive show.

It uses cutting edge LED technology to replicate different light conditions that can change the way the brain perceives colour.

Through a neat piece of video trickery at the exhibition, the reds in the Degas hair painting can be made more vivid by changing the colours that surround the artwork.

"The reason why we can almost make the painting dance is that not all of the red pigments are the same," Mr Padfield explains.

"But under certain light conditions they will all look the same - even to people with normal colour vision."

According to the Colour Blind Awareness organisation, colour blindness affects approximately 1 in 12 men (8%) and 1 in 200 women in the world.

In Britain there are approximately 2.7m colour blind people, most of whom are male.

Most people inherit deficient colour vision from their mother, although some people become colour-blind as a result of disease, ageing or through medication.

Most colour-blind people still see a world of vibrant colour. The most common form results in confusion between red and green.

Does it matter that they don't see works of art in exactly the same way as others?

"Art is about individual taste," says Kathryn Albany-Ward, who founded Colour Blind Awareness.

"Everyone knows someone who's colour-blind and think they get on fine."

Her concern is that a lack of knowledge about the condition in schools can lead to colour-blind children feeling a lack of confidence in the classroom - especially when it comes to art.

"If they haven't had their crayons marked up with the right colour they might colour the sky partly blue and partly purple.

"It's that kind of issue that can make people embarrassed. Children at school can be laughed at and it puts them off art potentially."

One colour blind-man who wasn't put off is artist Justin Robertson, who is based in Fife, Scotland.

This work by colour-blind artist Justin Robertson illustrates how he once avoided the use of natural colour

He's been making a living from mainly Pop Art-style creations for 10 years but admits he spent the early years working mainly in back and white due to a lack of confidence about colour.

The colours he has problems with are red, brown, blue, purple, green and yellow.

"About three years ago I started experimenting with skin tones," he says.

"I do still get stuff wrong. I did a Paul Weller painting last year. I thought I'd got the skin tones - and it turned out he was green."

His art tutor at college encouraged him to use his colour blindness as a unique selling point.

These works by Justin Robertson show how he moved from contrasting colours towards real world colours

"It has been hard over the years - not being able to offer customers portraits in colour has held me back, but now that's changed and I can offer the same kind of service as other artists," he says.

"I'll try my hand at anything. I haven't had a complaint yet."

As the science experts at the National Gallery point out, people shouldn't really be called colour-blind - they just "see the world differently".

Making Colour is at the National Gallery in London until 7 September

- Published7 February 2013

- Published12 March 2012

- Published15 February 2012

- Published17 April 2011