Metropolitan Opera delays staff lockout in late talks

- Published

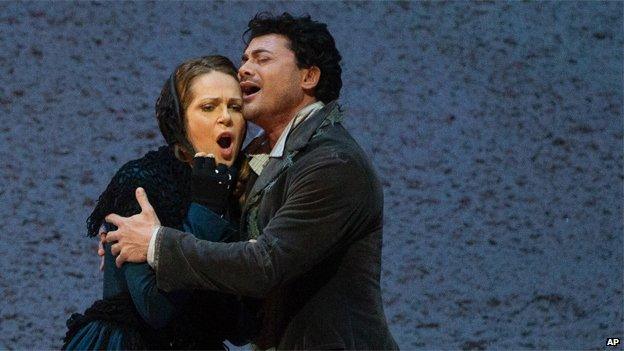

The Met's many Live in HD broadcasts have included Puccini's La Boheme

The Metropolitan Opera in New York says it has avoided a staff lockout in last-minute negotiations with unions.

The company had planned to close its doors to union members if new contracts, with reduced benefits, could not be agreed by 1 August.

But a 72-hour extension has been agreed to allow more time for discussions.

Most of the unions have so far rejected less generous contracts, raising the possibility of work stopping just weeks before a new season opens.

The Metropolitan Opera in New York could be on the brink of a shutdown. Nick Bryant reports.

In a statement, the company said negotiations with unions would continue through the weekend at the request of an independent mediator.

The mediator was brought in only hours before a deadline set by the Met for staff to sign new contracts or face being shut out of the building.

"We want to work together with union representatives, and do everything we can to achieve new contracts, which is why we've agreed to an extension," said the Met's General Manager Peter Gelb.

The company also said it had reached agreements with three unions representing support staff.

"Our goal was to avoid a lockout tonight," singers' union chief Alan Gordon told the Wall Street Journal, external.

"We achieved that goal. We'll see what happens after this."

It is still unclear if the extension will avoid a work stoppage or simply delay it until next week.

Mr Gelb had threatened to close the doors on employees unless they accepted cuts in their overtime pay, pensions and other benefits.

With contracts due to expire at the end of July, the Met had offered new, five-year deals to its musicians, chorus and stagehands, which include a leaner benefits package.

The company said it could save up to 17% in costs by making changes such as reducing paid holiday entitlements.

It insists it can make the savings without reducing base pay rates for its staff.

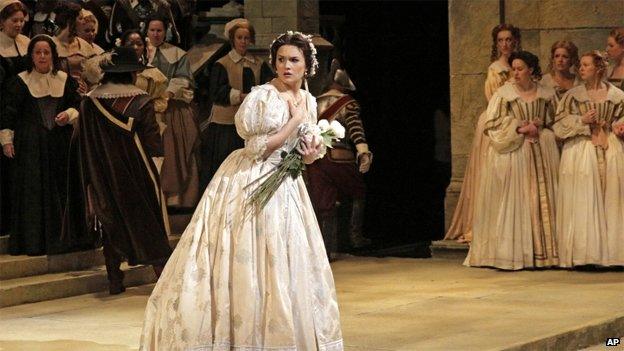

Olga Peretyatko appeared at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in Vincenzo Bellini’s I Puritani

With a production of Mozart's Marriage of Figaro due to open on 22 September, a lockout could derail the Met's forthcoming season before it has even begun.

The Met says it is facing "one of the biggest financial challenges in its 131-year history".

And Mr Gelb warned earlier that opera as an artform could disappear "if measures are not taken to make it fit in the 21st Century economy".

But it is Mr Gelb himself who is blamed by the unions for the Met's declining fortunes. They say his productions have been far too extravagant.

A recent production of Borodin's Prince Igor included a spectacular poppy field set that cost $169,000 (£100,000).

But Mr Gelb told the BBC last month the cost was justified. "A hundred and sixty-nine thousand dollars for an entire scene of an opera is not a lot of money," he said.

"It was the main visual component of the piece and, in fact, Prince Igor was acclaimed by critics as perhaps the greatest production of the Met season."

He also pointed to cost savings through co-productions with other companies such as English National Opera.

- Published7 June 2014

- Published1 October 2013