The North has always been a powerhouse for culture

- Published

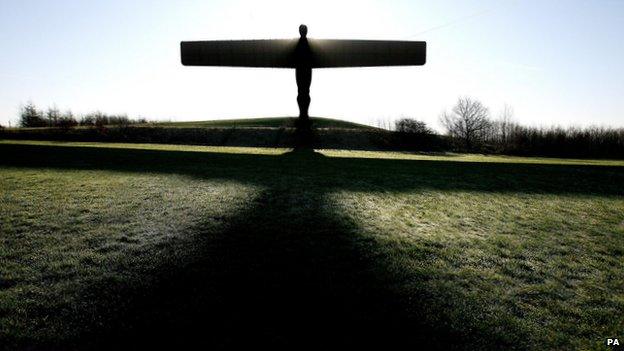

The Angel of the North became a symbol of the regeneration of the North East when it was erected in 1998

Merseybeat and Madchester. Coronation Street and Our Friends in the North. David Hockney and Henry Moore. Much of the UK's great culture has come from the north of England.

Measures to stimulate creativity further are now part of the government's plans to build a "northern powerhouse", alongside schemes to improve transport and the economy.

In the late 1980s and early '90s, Manchester ruled the musical world.

The Smiths and The Stone Roses were kings and the ecstasy-fuelled Madchester music scene revolved around the Factory Records label, its nightclub the Hacienda and bands like the Happy Mondays and New Order.

With painful industrial decline, followed by a recession, the government's main contribution to this explosion of creativity was to give a generation of young people the desire for some kind of escape.

So what would the late, lamented, left-wing Factory Records supremo Tony Wilson have made of the current chancellor's recent Autumn Statement?

Manchester-born Steve Coogan (left) played Factory Records boss Tony Wilson in 24 Hour Party People

Here was a Conservative chancellor announcing measures to help Wilson's beloved home city, including, among other things, £78m for a new theatre and arts venue. It will be named after Wilson's label.

"Did you see the new name of The Factory? I listened to all of the music," George Osborne later told the Manchester Evening News, external. "Tony Wilson would have had a smile on his face."

Madchester is proof that great cultural movements do not need a government grant.

But no-one in Manchester is turning their nose up at £78m.

The Factory will be an "ultra-flexible arts space" to host theatre shows, big art installations and immersive performances for audiences of 2,200 when seated or 5,000 standing.

The Manchester International Festival has hosted Sir Kenneth Branagh and Bjork in recent years

It is intended to be a permanent home for events normally seen at the biennial Manchester International Festival [MIF], which has hosted Bjork in a disused Victorian market hall, Massive Attack in a derelict railway depot and Sir Kenneth Branagh in a deconsecrated church.

"There was a collective realisation that Manchester needed this sort of space on a permanent basis," Maria Balshaw, director of the Manchester City and Whitworth art galleries, told Creative Tourist, external.

MIF has been a huge success since its launch in 2007 and the city council supports it to the tune of £2m per festival in the knowledge that it attracts visitors and prestige. But whether the city can sustain these events every week of every year, rather than for two weeks every two years, remains to be seen.

Sceptics have also questioned whether Manchester needs another arts centre.

The Whitworth gallery is reopening in February after being redeveloped at a cost of £15m, and the city's merged Library Theatre and Cornerhouse gallery and cinema will move to a new £25m building named Home, external, less than a mile from the proposed Factory site, in May.

Is The Factory really the best way to spend £78m?

That could pay for three Homes. Or it could cover Arts Council England's annual funding for all theatres, galleries, orchestras, dance organisations and opera companies in the north of England for a year (with some to spare).

That is not to mention the libraries, youth facilities, swimming pools and other under-strain services it could be spent on.

At a time when more cuts from the Arts Council and local councils seem inevitable (The Stage newspaper, external recently warned of a "nuclear winter" for arts funding), some question the logic of spending so much on another new building.

Landmark TV drama Our Friends in the North was the product of northern acting and writing talent

And why Manchester anyway?

The government seems to be setting Manchester up as the hub of its northern powerhouse.

With The Factory and - hopefully - a new high-speed rail link, perhaps artists and audiences will travel from Liverpool to Manchester to Leeds as readily as they go across London on the Central Line.

The aim of the northern powerhouse seems to be to create a region that can rival London. If the cultural treasures of the north could be put together, they would certainly do that.

As well as its unparalleled musical history, the north has produced a particularly great crop of comedians (think Victoria Wood, Steve Coogan and Peter Kay) and dramatists (like Alan Bennett, Jimmy McGovern and Paul Abbott).

Many performers, writers and directors have moved to London over the years to further their careers, though.

MediaCityUK, a major BBC base in Salford has boosted TV production in the region in recent years, while Yorkshire is also very busy with movie and TV filming.

The new Everyman theatre in Liverpool was named the UK's best new building in October

Bradford's National Media Museum, the product of an earlier policy of cultural decentralisation, has been under threat, and deserves more support.

In visual art, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park near Wakefield deservedly won the Art Fund's museum of the year prize in July and the bold Hepworth gallery in Wakefield has quickly established a world-class reputation.

In his Autumn Statement, the chancellor also announced money for a "Great Exhibition" to celebrate the art, culture and design of the north.

That could be held somewhere like the Baltic gallery in Gateshead, given the record-breaking popularity of its Turner Prize exhibition in 2011.

But with Hockney's recent retreat from Bridlington to LA, and with London always irresistible to up-and-coming talent, resident world-class artists are thin on the ground. Perhaps The Factory will make some small difference to the cultural brain drain.

In 2017, Hull will benefit from being UK City of Culture and Leeds is likely to bid to be European Capital of Culture in 2023 - the same title that did so well for Liverpool in 2008.

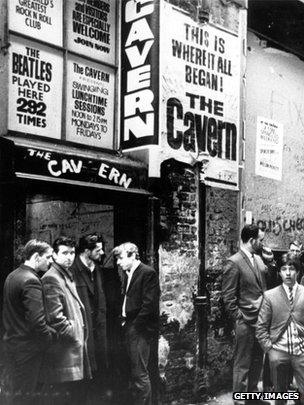

The Cavern, a humble basement club in Liverpool, was the birthplace of the biggest band in the world

Liverpool recently had another boost when the Everyman Theatre was rebuilt, winning the Stirling Prize for architecture in October. Its sister venue, The Playhouse, is next for refurbishment.

Meanwhile, theatres in Leeds and Sheffield are among the most dynamic in the UK - with Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Scarborough, Bolton and others thriving too.

The picture is healthy, and hopefully initiatives like The Factory will build on what is already there.

But in reality, how much do the cultural gems of the north have in common, apart from the fact that they all in the top half of England?

Their home cities may only be 30 miles apart, but Merseybeat had nothing to do with Manchester, and Madchester did not need Liverpool's help.

A high-speed rail connection might bring them a little closer together, but will it erode those cities' identities and pride or the rivalry between them?

The north will never be one unified, homogeneous zone.

The Factory will attract audiences and artists, but Manchester - or any part of the north - will never truly rival the concentration of talent and facilities in London, or the capital's allure.

Nor should it. History has proved that the north can offer something brilliant and different that the rest of the world wants.

A quote from Tony Wilson has become the city's unofficial motto, now printed on T-shirts and mugs and tea towels: "This is Manchester. We do things differently here."

- Published3 December 2014

- Published28 February 2014

brianroberts.jpg)

- Published10 August 2013

- Published22 May 2012

- Published30 August 2011