The state of UK theatre: Boom or bust?

- Published

The National Theatre's Curious Incident... has flown to the West End, Broadway and beyond

A few years ago, the theatre establishment mobilised stars from Danny Boyle to Dame Helen Mirren to warn about funding cuts. New figures suggest theatres have actually increased production levels in recent years. So what is the story behind the stats?

There is a premier league of leading subsidised theatre companies that can take their hit shows to the West End, to Broadway and into cinemas, attract private funding and lure top talent.

And the gap between that top tier and other publicly-funded theatres is growing.

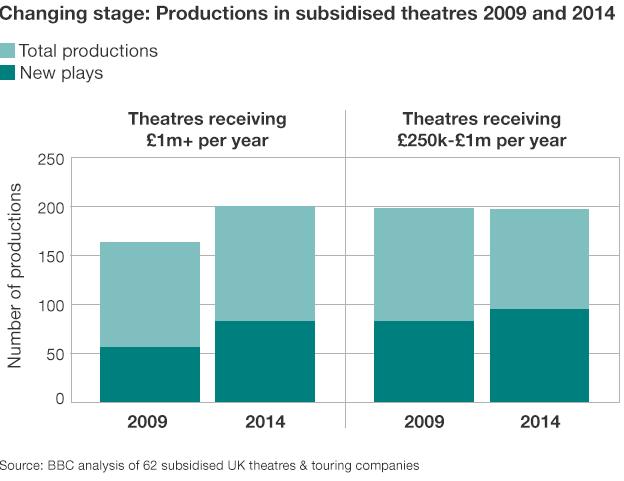

That is one conclusion that can be drawn from BBC research comparing production levels in 2009 and 2014.

This research analysed 20 theatres that each get more than £1m per year in government grants, plus a further 42 venues and touring production companies that get between £250,000 and £1m per year.

I compared production levels in 2009 and 2014 because 2009 was before the latest cuts began, and five years is a nice number.

I was expecting to find a story about theatres cutting production numbers and cutting new writing.

What has emerged is a different story - one of most theatres finding ways to deal with the cuts while maintaining, or increasing, production levels and new writing.

They have become more efficient, more resourceful and more entrepreneurial, without simply playing it safe.

At the 20 best-funded theatres, which each get more than £1m per year, there were 23% more full professional productions in 2014 compared with five years earlier.

That is despite a total government funding cut of 2.1% to those theatres between 2009/10 and 2014/15 (not seismic - but around 19% once inflation is taken into account).

The 42 smaller companies have had their government grants cut by 0.25% over those five years - or 17% in real terms.

At these 42 lesser-funded venues and touring companies, the numbers of shows have not gone up, but nor have they dropped significantly.

And despite the received wisdom that new plays get cut when times are tough because they are more difficult to sell, there has in fact been a rise in new writing.

Birmingham Rep presented the RSC production of A Life of Galileo in 2014

Who is in the premier league?

The National Theatre gets the biggest government grant, at £17.6m. But that is down by £1.6m, or 9%, since 2009.

However, box office takings from the National's hit shows have shot up in that time.

War Horse, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and One Man Two Guvnors have all been to the West End and Broadway as well as on tour.

Some 492,000 people bought tickets for National shows in the West End and on tour in 2009/10. That quadrupled to two million in 2013/14.

So when the National needed £1.7m to build The Shed, a temporary theatre specialising in new writing while one of its auditoria was being refurbished in 2013 and '14, the money came from War Horse's Broadway profits.

Therefore, War Horse paid for a new play about gender politics inspired by the controversial single Blurred Lines, a drama set in a homeless hostel and a thriller about a family holiday gone wrong.

It is an example of how a major subsidised theatre has become more commercial - and used its new income to pay for riskier new work that may go on to be the next hit.

'Staggering' fundraising

The National Theatre is top of this theatrical league.

Also up there is the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), which balanced its Bardic staples with West End and Broadway runs of its adaptation of Roald Dahl's Matilda and a festival of new plays by women last year.

The National Theatre of Scotland had a West End transfer of Let The Right One In, as well as staging new musicals about eccentric poet Ivor Cutler and teenage girls who fought a friend's deportation.

At the Young Vic in London, new works tackled topics from Syria to synesthesia, while the venue took its crowd-pleasing productions of The Scottsboro Boys and A Doll's House to the West End.

The Young Vic's latest annual accounts also revealed a "staggering" £1.3m in fundraising from trusts, individuals and corporate sponsors in 2013/14. There has also been an "increase in major donations" at London's Royal Court.

Chichester Festival Theatre has a strong track record for West End transfers

The 20 best-funded theatres also include the Birmingham Rep, which gained an extra auditorium when it moved into a refurbished building in 2013. Chichester Festival Theatre remains the regional theatre with the best track record for London transfers.

At the West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds, annual audience figures were up 16% in 2013/14 and there has been a "step change" in fundraising, while the Theatre Royal Plymouth is increasing its production levels, including a "major increase" in new writing.

These venues will point out that any progress is down to much hard work and ingenuity, and that they are still buffeted by the prevailing economic winds.

The Bristol Old Vic, another member of the £1m+ club, said it "fell considerably short" of box office targets in 2013/14, the Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse says the economic climate poses a "significant threat", while the Birmingham Rep says this year is a "tipping point" where none of its shows can afford to lose money.

Beyond the top 20, the lesser-funded theatres and touring companies have been required to work hard and come up with equally ingenious ideas to maintain production levels and standards.

It is just that they, on the whole, have fewer options - especially outside London.

'A miracle'

Do these production numbers tell the whole story?

"Absolutely it's a sign of good health and resourcefulness," says Rachel Tackley, president of trade body UK Theatre and director of English Touring Theatre.

"It seems like a bit of a miracle really that we've managed to produce more with less, and more new work as well."

But others see it differently. Actors' union Equity says actors are working for fewer weeks in total at the best-subsidised theatres.

It has figures for "actor weeks" at 16 of the 20 leading theatres examined for the BBC research. They show that actors worked for 15% fewer weeks in 2013/14 compared with 2009/10.

Smaller casts

"What I think that shows is that while the number of productions has gone up, the level of production hasn't," says Alistair Smith, editor of The Stage newspaper.

"What that would seem to indicate is that it's a change in the business model, moving away from the more traditional producing theatre model of having shows sit down for quite a long time and run for a month or so, to a model where you have more shows doing shorter runs, possibly with smaller casts as well."

The future outlook for the economic climate is still stormy, and the strong fear in the world of theatre is that we ain't seen nothing yet.

Central government will need to make more big cuts, while local authorities, which also fund many arts organisations, will also come under more financial pressure.

Many of the best-funded theatres have put themselves in a relatively strong position. Other companies may struggle more.

But if there is one rule in theatreland, it is that the show must go on.

- Published4 February 2015

- Published4 February 2015

- Published4 February 2015

jonathankeenan.jpg)