In quotes: Theatres are 'incredibly tenacious'

- Published

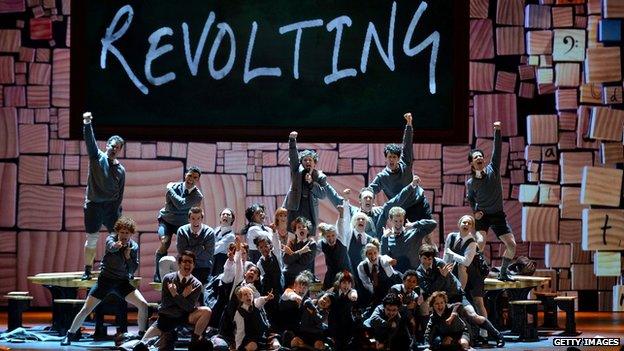

The Royal Shakespeare Company has had a hit with its adaptation of Roald Dahl's Matilda

Is production really booming at subsidised British theatres? What effect have funding cuts had?

BBC research suggests production levels are up in the last five years. Here, figures from the theatre industry shed a bit of light on the state of play.

Rachel Tackley, president of UK Theatre and director of English Touring Theatre

Data collected by trade body UK Theatre since 2012 has found production levels have been rising in recent years, Tackley says.

"The bigger houses are definitely becoming more resourceful and doing more co-productions," she says.

"I wonder whether the bigger houses have got more space to play with and using the space they have more efficiently."

Venues are "working together to make what there is go further", she continues. "People that run theatres want to keep the quality of work really, really high and do as much as we possibly can.

"The easy thing would be to do less. The money gets less, we do less. Actually I think the opposite has proven to be the case. As the money gets tighter and we're more squeezed, then we get more and more resourceful. My worry is to what extent you can continue that."

Martin Brown, assistant general secretary, Equity

Figures from the actors' union show the number of "actor weeks" at a range of the best-funded venues has dropped by 15% in recent years.

"By and large, with some exceptions, theatres have dropped the number of actors working on stage between 2009 and 2014. The picture for the regional reps is, overall, a drop in employment for actors."

Referring to the rise in numbers of plays staged by the UK's best-funded theatre companies, he says: "We don't think that more titles being done by these 20 theatres can be read as a sign of theatres not being impacted by funding cuts, especially when you look at the collapse in employment in most of those theatres."

Is the rise in production numbers a good or a bad thing? "Don't know really," he says. "It means that if you're a citizen in Nottingham, for example, then you've got 10 things to choose from all year rather than eight, so it's good for audience choice.

"It doesn't mean the theatre is necessarily open any more than it was, but there's more variety."

In the West End, a higher turnover of productions is not good news because it means more shows have flopped. "Rep theatres aren't the same but I wonder whether more productions means some stuff hasn't worked and they've taken it off and put something else on," he adds.

Roxana Silbert, artistic director, Birmingham Rep

The Birmingham Rep moved into a refurbished building with a new studio space in 2013. The company is now staging more productions - but is giving them shorter runs and doing more co-productions.

The venue also put on more new plays in 2014. "I think a real change in the way audiences go to the theatre has happened in the last five years," Silbert says.

"Regionally, there are classic plays that one always assumed would do well, and what's really interesting at the moment is that's no longer true.

"Things that you would have assumed would have sold really well - your Ibsens and Chekhovs and classical works - are not necessarily selling in the same way. There's much more appetite among audiences for new plays."

However, after funding cuts, the theatre has reached a "tipping point" where it cannot afford for any of its productions to lose money, Silbert adds.

"The Arts Council pays for our overheads and to keep ticket prices down, but what I can't do is programme work that loses money. Nothing I programme can now lose money because of this last round of cuts."

Fin Kennedy, artistic director, Tamasha theatre company

"A rise in new plays is a headline to be welcomed," Kennedy says. "But it's something of a crude measure with which to really get to grips with the full complexity of how theatre is made, particularly new theatre."

Tamasha is a touring company that puts much time, effort and money into finding new black and minority ethnic writers.

Regional venues have become less willing to offer guaranteed fees for their shows, he says. Instead, they increasingly offer a split of box office takings.

"It almost always works out as less income for the touring company and it's understandable because regional venues are being squeezed, not just from the Arts Council but from local councils and audiences with less to spend. But it makes it increasingly economically difficult to tour small-scale work."

New plays take a long time to come to fruition, according to Kennedy, who is currently beginning to plan his 2019-21 seasons.

And he is also concerned further cuts will hit the ability of companies like his to seek out a diverse range of writers.

"Theatre's not going to go away - it's just going to get narrower and narrower and that would be a real tragedy because I think ultimately it's not sustainable if it's just a plaything of the metropolitan middle classes," he says.

David Thacker, artistic director, Bolton Octagon

Thacker, a former artistic director of the Young Vic in London, moved to Bolton six years ago. When he joined, the theatre's productions needed to make a surplus of £67,000 per year in order to balance the books.

Now, that figure is £200,000. "The challenge of mounting a season of productions that is going to generate more than £200,000 surplus at the box office is a very big challenge - not least if you're trying to make sure you produce a range of work and keep up high production standards," he says.

"I feel proud of what we've done but also very conscious of how hard it's going to be in the future."

Production budgets for things like sets and costumes have also been cut by 20% since he arrived.

But the venue is coming up with new solutions, like a partnership with the University of Bolton, which will see Thacker become professor of theatre. The theatre will get a slice of the students' fees and the university will increase its sponsorship of certain shows.

"In essence they will be co-productions of a different kind," Thacker says. "That will enable us to do plays with larger casts - for example to continue to do Shakespeare and continue to do great plays from the American canon. I think it's going to be very important."

Chris Monks, artistic director, Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough

The Stephen Joseph theatre is Sir Alan Ayckbourn's home venue and is where the stage adaptation of The Woman in Black and Tim Firth's Neville's Island were born.

New writing is key - and that is not about to change.

"When the chips are down, you have to do something extraordinary," Monks says. "That's what people want to come to see live entertainment for. They want something special, not that they're going to get from the television or cinema."

But these days, the venue has to think hard about which new plays to stage, in which auditorium and for how long.

"It's really quite tough," Monks says. "When I first started, if you put on a new play and nobody came to see it you just went, 'Oh well, they'll come and see the next one.'

"It's not like that any more," he goes on with an agonised laugh. "But you've just got to do the thinking and the preparation really well and make sure that you really critique the author and don't end up with something that's not as good as it could be."

Erica Whyman, deputy artistic director, Royal Shakespeare Company

Whyman was given a brief to think about new writing when she joined the RSC two years ago. She has just directed The Christmas Truce, a new play, and last summer staged a festival of new work by female writers.

She says: "The trouble with cuts to the culture budget is they take a long while to show because people are incredibly tenacious and they find ways through and audiences keep you going for a time.

"Then the juggling act just can't be done any more - I do fear we haven't seen the worst of it."

One of the RSC's biggest recent hits has been its adaptation of Roald Dahl's Matilda - which has gone on to play the West End and Broadway.

"We are investing some of the profits from Matilda into the development of new work," she says. "We are very cautious and careful to make sure money does not replace any revenue money - regular money - because it won't last. It doesn't matter how successful it is, or how long it runs, it won't last."

James Grieve, artistic director, Paines Plough

The number of productions staged by Paines Plough - a touring company specialising in new work - shot up between 2009 and 2014. That was a deliberate five-year plan, Grieve says. "We've done that by co-producing heavily.

"In the last five years, we've started co-producing with multiple partners on each show - often [with] several different buildings, other companies and all manner of people. So that's enabled us to increase the amount of work we produce."

It has allowed the company to share the resources and expertise of bigger companies. "People in this industry are very collaborative and we have bunkered down in the last few years in the face of quite significant financial cuts and tried to work out ways in which we can keep going productively," he says.

However, it has become more difficult to book new plays in regional venues, he explains: "I'm really concerned about the future and the threat that is posed to new plays by the continual cutting of the Arts Council's budget. I think new plays will be the first to suffer.

"It would be a huge mistake on the part of the government to think just because we've survived this far they can keep cutting us and we will keep bouncing back. I don't think that will be the case."

- Published4 February 2015

- Published4 February 2015

- Published4 February 2015

jonathankeenan.jpg)