How Newcastle's arts venues survived cuts

- Published

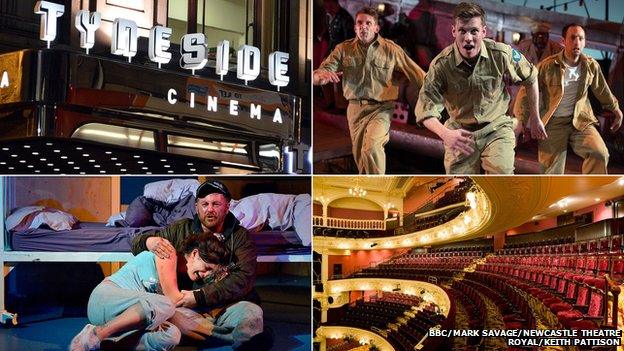

Venues including the Tyneside Cinema, Northern Stage, Theatre Royal and Live Theatre have had budgets cut

There were howls of protest in 2012 when Newcastle City Council said it would be the first British city to scrap funding for theatres, galleries and other arts venues. A compromise was found, and venues are now finding new ways to survive.

A "cultural wasteland" was the fate writer Lee Hall - who set stories like Billy Elliot and the Pitmen Painters in north-east England - predicted for his home city.

"The tumbleweed will start blowing up the cultural streets here," he warned in 2013 after Newcastle City Council put forward a plan to axe its £1.2m annual arts budget.

Opposition such as this led the council to search down the back of the sofa and eventually come up with £600,000 per year - half the previous amount - for a new cultural fund, which kicks in this week.

After a bidding process, 15 organisations have been given three-year grants. Six of those had not previously received regular council funding.

But the established theatres, museums, galleries and independent cinemas have received deep cuts. Two - the Globe gallery and the 178-year-old Theatre Royal - were cut out altogether.

The Newcastle Theatre Royal has introduced booking fees and is staging more crowd-pleasing musicals

The Theatre Royal is the biggest loser. Three years ago, it received £630,000 per year from the city council. From 1 April, it will get nothing.

But the tumbleweed is not blowing down Grey Street yet.

The grand old venue has compensated for the lost grant by introducing booking fees, taking a bigger slice of box office takings from touring shows, changing its education activities and staging more crowd-pleasing shows.

"We do tend to put on more musicals, we do tend to put on a bit less drama than we did," Theatre Royal chief executive Philip Bernays says. "The balance has shifted.

"It's an inevitability of the government's policy coming through to the local authorities coming through to us. That slightly more challenging work that we did sometimes present, we're now simply not able to afford to."

Audience numbers have increased, Mr Bernays says.

"Ticket income has gone up and, actually, we have found that we've been able to make up the shortfall from the council funding."

Live Theatre's new Live Works office block is being built, overlooked by the Sage Gateshead concert hall

Meanwhile, down on the quayside, workers are busy erecting the steel frame of an office building that will overlook the River Tyne.

It will be owned by the nearby Live Theatre.

With 170 seats, Live Theatre is far smaller than the Theatre Royal and specialises in new plays. Lee Hall and Peter Straughan - who wrote the Wolf Hall TV script - cut their teeth there.

"You have to think of us as an R&D [research and development] house for the rest of the theatre industry," Live Theatre chief executive Jim Beirne says.

Live will never resort to mainstream musicals and would have to increase ticket prices by three or four times to become self-sufficient, Mr Beirne says.

"Those options are not open to us in the same way that they are to Philip at the Theatre Royal. So we have had to think of doing different things."

Ten-year plan

This is where the office block comes in. Rents from the 14,400-sq-ft (1,337-sq-m) building, named Live Works, external, will be ploughed back into the theatre and a new youth writing centre that is also under construction.

Although the theatre's annual council grant has effectively been cut by 70%, the authority has provided a £6m loan for Live Works at lower interest rates than a bank could offer.

As well as Live Works, the theatre also owns a gastropub, a creative business hub and an online playwriting course.

Those schemes together should earn the theatre £500,000 a year - double the amount of public funding it will have lost - Mr Beirne predicts.

Live Theatre started thinking about new sources of income 10 years ago - and the rest of the arts world is now following its lead.

"Everybody is now thinking about how they are going to do without local authority resource or Arts Council investment," Mr Beirne says.

Northern Stage now hosts conferences and creativity workshops for entrepreneurs - as well as plays

Elsewhere, the council has given a loan to the Tyneside Cinema to open a cafe and bar in a former building society on its ground floor, while Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children's Books, says it has redoubled its fundraising efforts.

The city's other major theatre, Northern Stage, is also exploring new ways to earn money.

It now hires out its auditoriums for conferences, exploits the expertise of its set-building and wardrobe departments, and its artistic director, Lorne Campbell, runs workshops in creativity and presentation for entrepreneurs and students.

He estimates he now spends at least 30% of his time on such commercial activities.

"They generate income, but it's weeks of my time and my team's time," Mr Campbell says. "We can do it. But we're a theatre."

Northern Stage has not cut back on plays or education work, he says.

'Invisible costs'

"We're doing a huge amount more than we were doing five or six years ago for far, far less money in real terms while also spending a lot more of our time and our resource generating income from other means.

"There comes a point where you hit the rocks with that."

Newcastle - like the national arts scene - is highly resilient, he says. But there are "invisible costs" to the cuts, he adds.

"As with all cuts, it hits the most vulnerable," he adds. "It hits diversity."

"Getting artists from any sort of deprivation - be it economic, be it social - getting artists from any sort of minority, getting the cultural life into those areas where it does not exist becomes the hardest thing to do as the economic resources become tighter and tighter."

For its part, the council insists it had little choice. It says it must save £90m over the next three years and is also making big cuts to areas such as youth services, social care and libraries.

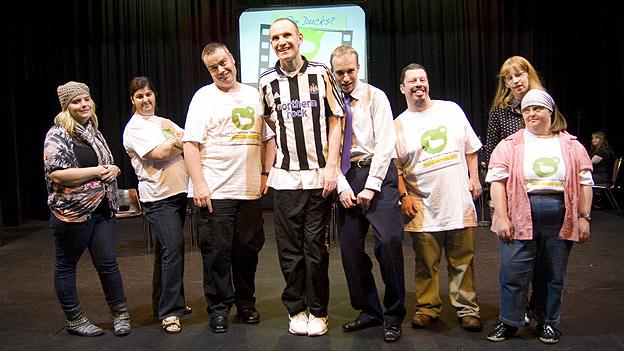

Twisting Ducks, a theatre company that works with people with learning disabilities, has gained council funding

"There were not a lot of places to go," according to council assistant director Tony Durcan, whose responsibilities include culture.

"It was incredibly difficult. At one stage we felt we would be left with no funding for culture, one library, one swimming pool, one customer service centre. It didn't turn out to be as bad as that. But we had to make some quite serious reductions."

The new culture fund has come from "a cocktail" of sources, including public health grants and interest on a loan the council made to Newcastle Airport.

With public health money in the mix, applicants have had to prove their contribution to the city's wellbeing.

As such, the biggest winners from the fund were Twisting Ducks, a theatre company that works with people with learning disabilities, which will receive £118,000 over the next three years.

'Difficult' philanthropy

The fund is being run by the Community Foundation, and the idea is that it will eventually be topped up by private donors.

"We've had one or two people who've approached us for modest amounts," Mr Durcan says. "Philanthropy for the arts isn't at a high level for the north of England so we know that will be difficult."

He praises "entrepreneurial" venues such as Live Theatre - but accepts that not every institution can go down a similar route.

"It still feels a very buoyant scene in the city," he adds. "It still produces excellent art. But I'm not being overly optimistic. I am saying it's early days."

'Awful' outlook

Newcastle is certainly not alone in seeing its local authority funding shrink. Most cities have cut their arts funding - along with other services.

In keeping the tumbleweed at bay, Newcastle's arts scene has shown what a bit of high-profile campaigning and creative enterprise can achieve. As austerity rumbles on, they will need to keep drawing on those skills.

"The future for local authorities is looking awful," Mr Durcan says. "The way we're looking, our budget over the next three years is particularly dire.

"You talk to colleagues in other cities and in two or three years, if things do not improve, we do not know how we will deliver even some basic public services."

- Published4 February 2015

- Published2 October 2014

- Published7 March 2013

- Published28 January 2013

- Published17 December 2012

- Published29 November 2012