How international arts festival helped reinvent Manchester

- Published

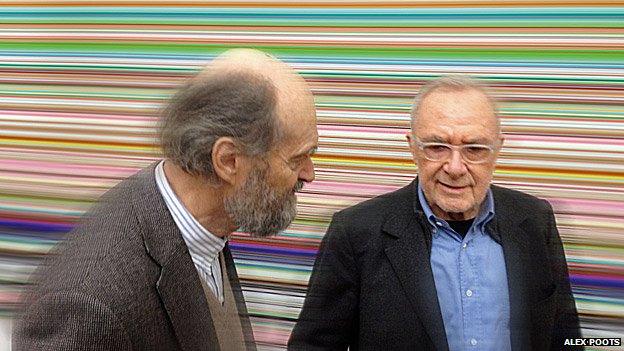

Alex Poots: "There's no such thing as too much culture - as long as it's good culture"

Every two years, Manchester becomes the coolest place on the world's cultural circuit as the Manchester International Festival (MIF) stages a string of art, theatre and music premieres. Artistic director Alex Poots has masterminded its first decade - but is now stepping down to run New York's new Culture Shed.

Alex Poots makes top artists and performers a simple offer.

He asks what their dream project is. And then he makes it happen.

That, in a nutshell, is how he has persuaded figures including actor Sir Kenneth Branagh, musician Bjork, performance artist Marina Abramovic, Blur's Damon Albarn and artist-turned-film-maker Steve McQueen to unveil new work in Manchester over the past decade.

And the festival has played a large part in transforming the city's reputation on the global cultural circuit.

"For the world at least, Manchester was previously just a city for soccer, not at all a cultural city," said Jean-Luc Choplin, director of the Theatre du Chatelet in Paris, after his company collaborated with MIF on Albarn's Chinese opera Monkey: Journey to the West in 2007.

"Suddenly with MIF, it is very clear that Manchester now belongs in the cultural map of the world."

Damon Albarn says Alice in Wonderland haunted him as a child

This year's festival opens on Thursday with Albarn's Alice in Wonderland musical, titled Wonder.land. The line-up also encompasses painter Gerhard Richter, composer Arvo Part, art-pop auteur FKA Twigs and children's TV star Justin Fletcher.

The reinvention of Manchester can be traced back, Poots says, to Tony Wilson's record label, Factory, which signed bands such as Joy Division and the Happy Mondays and ran the Hacienda nightclub.

"It showed that Manchester could do things differently, as Tony famously said, and could do it at the highest level, without the need to move to a major capital," Poots says.

The festival was born after the city staged the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

"From that experience, Manchester got a real confidence in putting on a big show, and [the city council] thought, very wisely, we've achieved that, what's the next thing we should be doing?"

Sir Kenneth Branagh and Alex Kingston starred in Macbeth in a deconsecrated church in 2013

Poots suggested a festival that would:

stage only new work

be led by artists

be independent of the council

be biennial

reflect Manchester's radical history and culture

The council offered him the job the same day.

The event's ethos and big names have earned it prestige and acclaim. But the festival has also had criticism.

Some say that, while the line-up may excite the artistic elite, most of it is too highbrow.

Bjork began her Biophilia tour in Manchester in 2011 and is returning this year

"I defy anyone with a curious mind not to go to the Whitworth art gallery and look at Gerhard Richter's paintings and not find something of value and interest in those," Poots says.

"And they are supposedly high art. So for all the people that who think high art is not for them - it's just like saying good food is not for them. It doesn't make any sense to me.

"There are certain artistic languages that are more difficult than others - certain aspects of modernist classical music require more research and a bit more time to get into it. But that's a joy. Spend the time with it.

"And if you don't want to spend the time with it, then fine. But don't annex it off as some weird museum piece that should just be viewed with scepticism.

"Culture is a wonderful enriching thing and people should savour it. There's no such thing as too much culture. As long as it's good culture."

Another criticism is that the festival works with the same artists - such as Albarn - too often.

Willem Dafoe and Mikhail Baryshnikov starred in The Old Woman at the last festival

Poots says: "Once you've got a relationship with someone like that, where you've really understood what they're doing and you've got to grips with what they want to achieve, the idea that you would just let that go seems very strange."

Albarn's Alice in Wonderland musical is an example, Poots says, of where a relationship has paid off.

He had been trying to persuade Albarn to write a musical, but had always been rebuffed - until he decided that Alice in Wonderland might tempt the musician.

"I knew that sense of Englishness and eccentricity and slight psychedelic aspect to what he writes, [and thought] that Alice in Wonderland was going to be the story that might inspire him," Poots says.

"I've just read the programme notes for Wonder.land, and it says he used to be haunted by the book as a child. He used to find it terrifying. I didn't know that."

Alex Poots introduced artist Gerhard Richter (right) and composer Arvo Part

That is another of the secrets of the festival's success - Poots and his artistic advisers have a knack of suggesting the right ideas to the right people.

This year's collaboration between Richter and Arvo Part grew out of a hunch that the pair would hit it off. So Poots and curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist spent nine months arranging for them to meet.

As a result, Richter has made paintings inspired by Part's music, and Part has composed a choral work inspired by Richter's art.

Unfortunately for the festival's claim to show only world premieres, Richter unveiled his paintings at the Basel art fair.

"To quote my seven-year-old daughter, it wasn't my favourite thing, that we were blissfully unaware that something was going to pop up in Basel that we felt very aligned with," Poots says.

"The perfect outcome would have been for those works to have been first manifested here. But they're two old giants of their forms, and they don't really comply to the rules. So it's OK."

Rock band Elbow joined forces with the Halle Orchestra in 2009

MIF is now firmly established. Elsewhere in the city, the Whitworth gallery has recently expanded, an arts centre called Home has opened and there are plans for a new £78m venue called The Factory.

The Factory was Poots' idea and will be able to host anything from 5,000 capacity pop concerts, opera and plays to art installations and MIF-style premieres by world-renowned companies.

Manchester's cultural scene will change as much in the next decade as it has in the last, Poots predicts.

"It all starts to add up and the whole thing starts to snowball.

"But fortunately there's still a way to go because it would be very depressing if we'd arrived at where we're trying to get to. I think there's still a way to go, which is exciting."

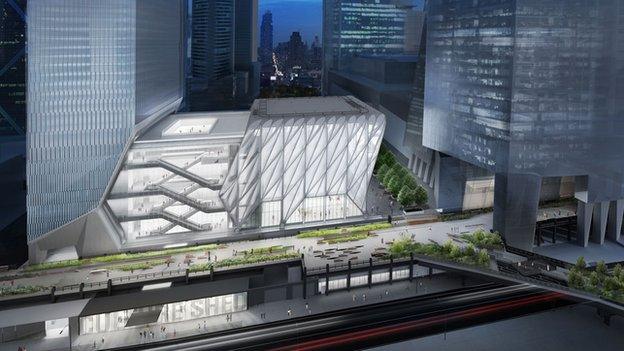

Building work on New York's new Culture Shed has begun

For Poots himself, this is the last festival before he moves to New York to set up a new venue called the Culture Shed, which will cost $360m (£229m) to build.

"At the moment it's a lot like MIF was 10 years ago - it's an idea with a lot of goodwill around it and a lot of brilliant men and women in America who have put their money where their mouth is."

He wants it to be "the centre for artistic and cultural innovation", where innovative minds can "develop new ways of working, new forms of art, innovation, culture".

A bit like MIF - only open all year round.

- Published13 May 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published25 November 2014

- Published3 December 2014