Why Matthew Bourne ballets are not just for Christmas

- Published

Bourne: 'I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for the audiences'

Choreographer Matthew Bourne - known for his modern takes on such ballet classics as Swan Lake - is where we've come to expect him at this time of year: ensconced within the walls of London's Sadler's Wells.

As one of the dance house's associate choreographers, and a local north London resident, Bourne is a familiar face at the leading venue. But at Christmas, he is the star of the show.

From Cinderella to Edward Scissorhands, a Bourne ballet has been the highlight of the Sadler's Wells Christmas bill for more than a decade - so much so he's been dubbed "Mr Christmas" by some.

This year he is presenting Sleeping Beauty. Despite Bourne's Santa pseudonym, though, there is very little that is Christmassy about his work.

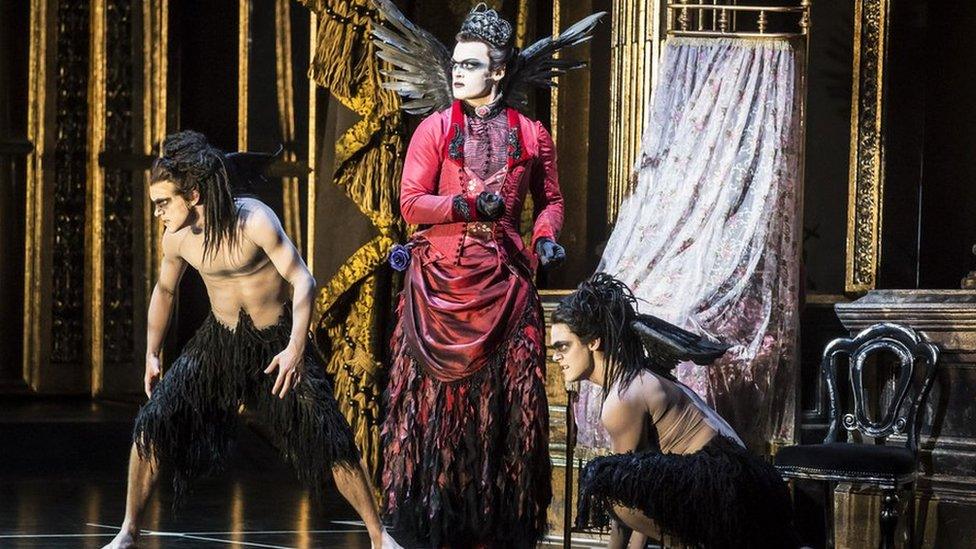

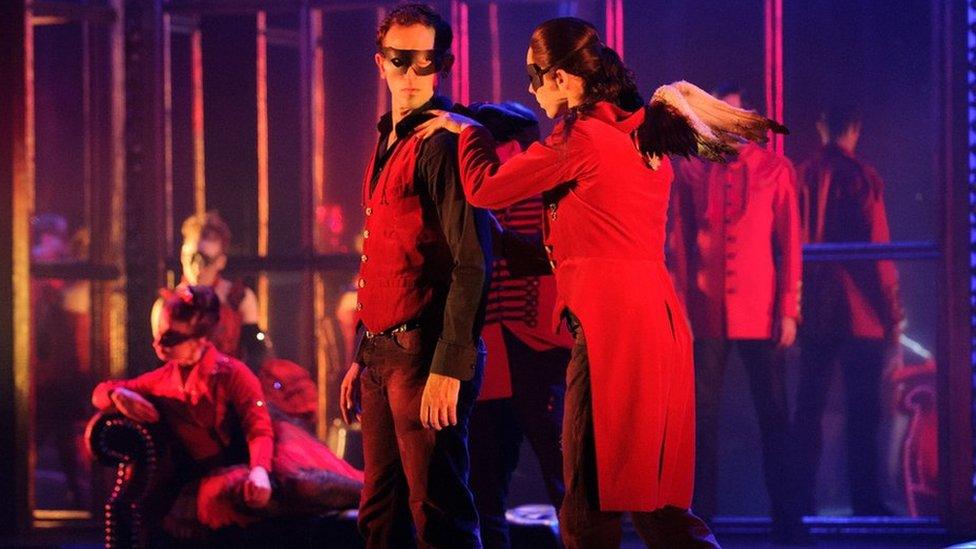

He's made the well-known Tchaikovsky classic feel contemporary with his trademark fast-paced choreography - and completely new with the "shock" element of a gothic vampire twist.

Here the crowd-pleaser tells us about the importance of the audience, his love of a great story and his future plans.

Bourne's Sleeping Beauty sees the heroine fall in love before she goes to sleep

How do you feel about being called "Mr Christmas"?

I've never seen myself as a Father Christmas figure, but I understand it sounds good although we're only in London over Christmas. We do 26 to 28 other venues in the rest of the year.

There are certain shows you can do at Christmas and others you can't, including at least half my repertoire. But anything with a fairy-tale background tends to work.

Do you feel the epithet encourages accusations from purists and the press of "dumbing down" for the sake of ticket sales?

I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for the audiences that keep coming. Over the years their loyalty around the country has been brilliant.

There is a sense the critics want to take me down a peg or two because we are so much more successful than any other dance company in this country, in terms of numbers and the amount of shows. But they have come along with me over the years, so a lot of them accept me more now.

Bourne: 'Swan Lake changed my life... but we weren't ready for the reaction'

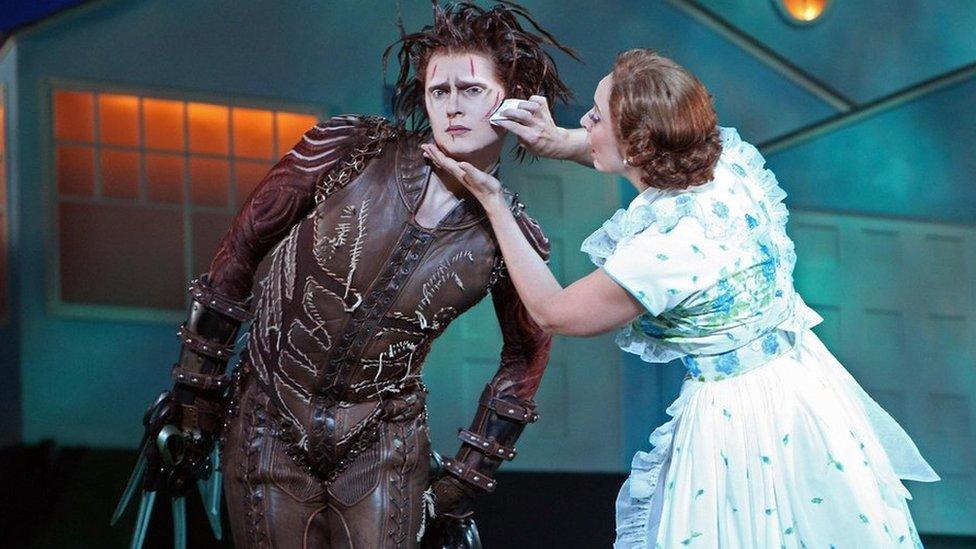

Edward Scissorhands is proof that no story is totally original, says Matthew Bourne

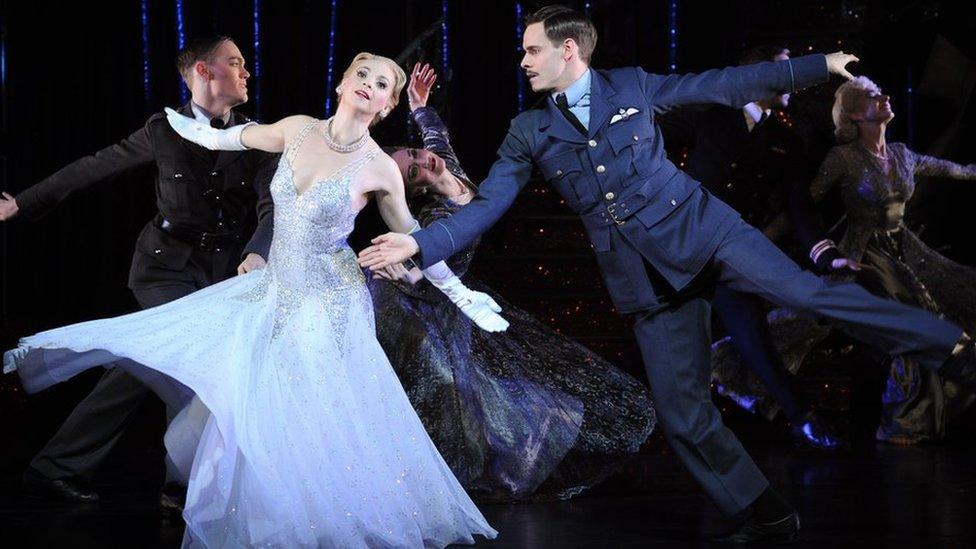

Cinderella's story is transferable to any era, says the choreographer

How have you experienced the effect of your work?

The other night I met a couple who hadn't seen much dance but had seen my Swan Lake and loved it so come back to see Sleeping Beauty. They said they'd been in tears 10 minutes in. It's lovely to hear. There's a level at which the public experience a piece that a critic just can't.

Is there also a freedom that comes from your status as a dance "maverick"?

Every company wants to please the public, but we can do it on a much wider scale as we are not tied to tradition. I do want the balletomanes and the critics to be happy and to understand how much I love these pieces and that I am telling the story in a different way.

Over the years, the standard of dancing in my company has gone up considerably. All our production standards are high, so if there is any criticism it can't be made on that level.

A lot of those you've worked with have described you as "generous".

I love audiences and in my own world of dance, where I've been now for a long time, I love promoting young dancers and choreographers so that's where I am generous. I don't see the point of making work if you're not thinking about the audience and if they are not reacting to it, I will keep on until they do.

I want my dancers to be generous with the audience. Curtain calls are very important. They smile and look genuine and are saying "thank you for coming". I want people to love the company and want to come back.

The vampire element of Sleeping Beauty brings colour and extra depth

Bourne wants costumes to look like they come from a film

Do you tinker with productions for each new performance?

A lot, sometimes every day. We've done this show almost 330 times, but even earlier this month we put new things in. There are always new ideas. Fans of the company, who book for two shows over the weekend - yes, they really do that - know they are going to get something different.

What's different about your choreography and your overall production style?

My choreography always serves the show, the period I've set it in and the style. It's always about narrative, character and stories and it's acrobatic. Costumes look like they come from film rather than being dance-adapted because we want the audience to relate to the scene.

We'll sometimes use normal shoes or even bare feet to make it look appropriate to the period and the choice of dancers is important too. They need to be faces you can relate to.

People expect to see something spectacular and that's also what I enjoy; I want people to go "wow". On stage, even simple things people love, like just dropping confetti. It's delightful.

The Car Man can't be shown in some countries because of its erotic and violent themes

Aren't you tempted to do a show that is pared-down and simple?

I do think about it from time to time. I love the simplicity of things sometimes. I'd like to do something that is completely dancer-led about space and light.

It would have to be an experiment as I don't want to lose the audience. My job is to make pieces work and make them accessible for a modern audience, not just a ballet audience.

You love a great story but you always want to change a classic. Why?

If the audience didn't know the story, as of course they do with Sleeping Beauty, I'd have to spell it out but this way allows me to be creative within the existing structure. Everyone gets it but then you can surprise them.

I set Cinderella within the Blitz of World War Two to make it completely new and exciting, but the basic premise of the bad relations and out-of-reach love is infinitely transferable. With Sleeping Beauty, it just wasn't a very good story - Tchaikovsky's music is the attraction.

Bourne and his New Adventures colleague Etta Murfitt plan a new production in 2016

Sleeping Beauty is a big hit, but can Bourne keep on emulating his own success?

You've clearly got a vivid imagination so why don't you write your own original stories - or even a book?

It comes from years of watching lots of movies and plays; my head is full of imagery. But I feel I do write my own stories already. I write my scenarios like stories because it has to make sense to me and marry well to the music. You have to justify going off on a tangent. Every story ever written is based on previous stories.

Do you have a favourite among the work you've produced?

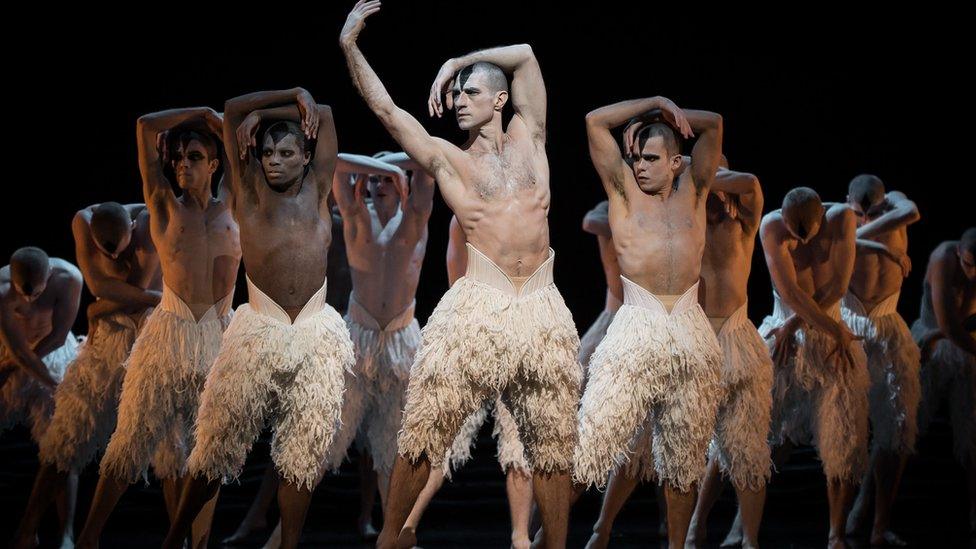

You need to love them all and want to do them again. Swan Lake changed my life and I am grateful: it made me well-known around the world, it was a news story rather than just an arts story. It wasn't my intention at all, though, and I was completely taken aback.

I believed in the idea - bringing in male swans since they do naturally exist but everyone assumes they should be female. It took a while to get used to, the success, the awards, the long run in the West End. It did huge things for us but put us back at first.

How did your upbringing influence you?

I grew up in north London and there was nothing in our household that you would call high-brow entertainment. I had to find a way to see a lot of things. I went to see an opera and ballet in my late teens as self-education.

My parents and I went to a lot of West End musicals and I loved it, but they didn't know ballet so when I got into it, they did too. So I reciprocated the education.

They were incredibly supportive and luckily lived long enough to see great things happen to me, such as going to Broadway and Los Angeles - they met lots of old movie stars and had a great time.

Your productions are performed all over the world. How is the reception different from country to country?

It varies a lot and that fascinates me, but that also applies from town to town in this country. Outside the UK, there are a lot of differences: humour and some themes can be a problem.

In Russia homosexuality is a problem, especially when it comes to keeping backers on side. We have done Swan Lake but they were worried about the gay element in The Car Man. They were okay with Dorian Gray as they said it was literature, which was odd to me.

Some audiences are very vocal, some very quiet. In Japan they are very silent but at the end you have to bow a lot - to the point of being embarrassing.

What's next?

I'm working on a new show for next year, brand new. I'm sworn to secrecy at the moment. But it will be opening in Plymouth and then Manchester. It's a fairly well-known story, I can say that, but I'm running out of titles.

Sleeping Beauty is at Sadler's Wells in London until 24 January.

- Published27 January 2014

- Published26 October 2011

- Published10 September 2013