Seamus Heaney: A fitting home for a much-loved poet

- Published

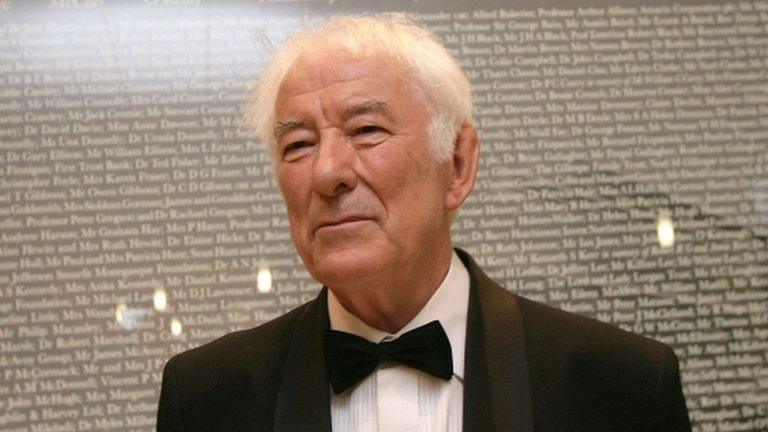

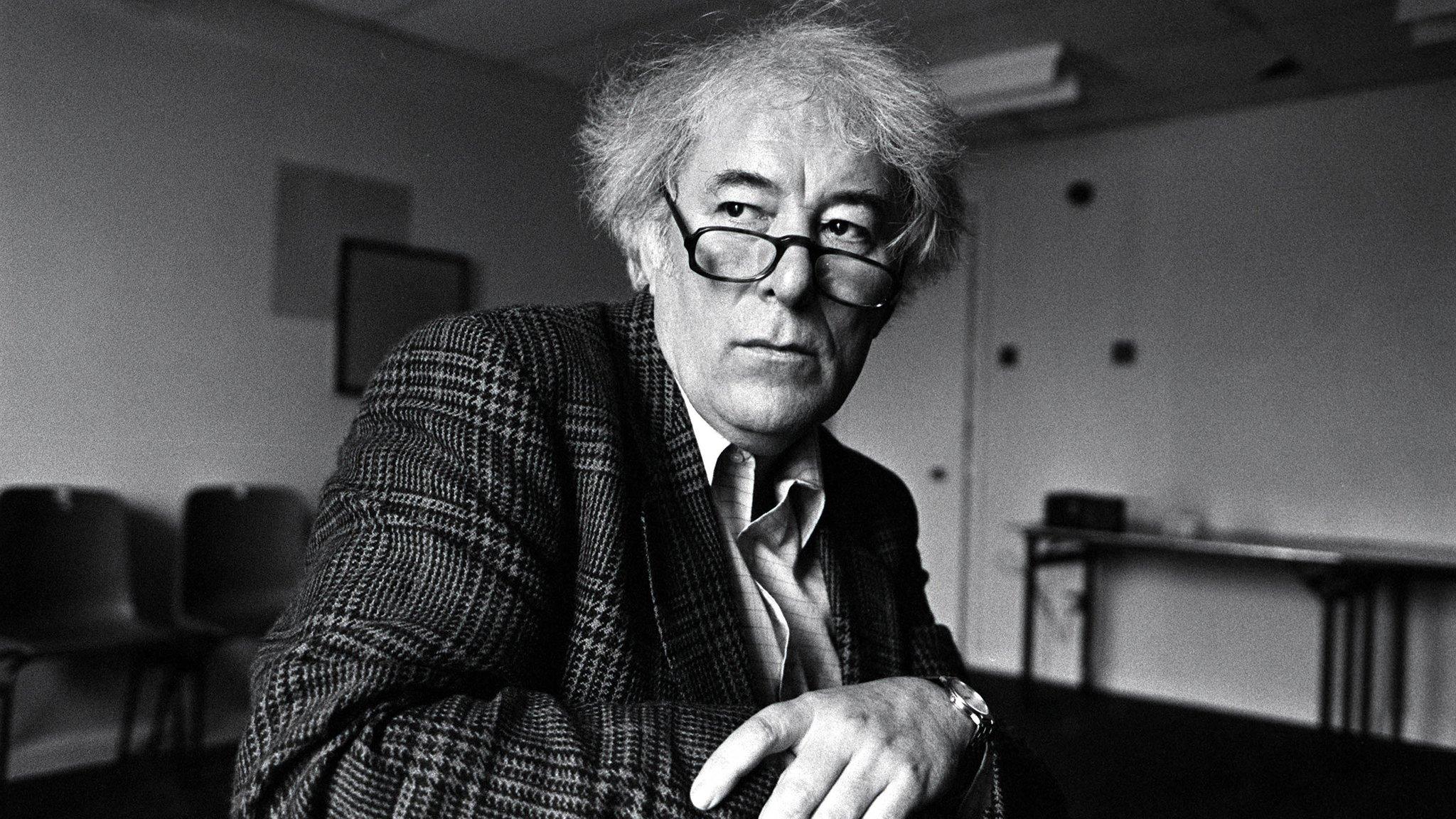

Seamus Heaney was a rare poet whose work meant something to people who normally take little or no interest in poetry

It has been three years since the Nobel Prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney died in Dublin. This week, a major new arts centre in his honour opens in the village of Bellaghy in Northern Ireland, where the writer grew up. Mick Heaney, who'll be travelling north for the opening, recalls growing up the son of "famous Seamus"- regularly acclaimed as Ireland's greatest poet since Yeats.

Seamus Heaney died at a clinic in Dublin's far southern suburbs. Few outside the family knew he was to be operated on for a heart condition: his death came as a huge shock to the literary world and well beyond.

Heaney was a rare poet whose work meant something to people who normally take little or no interest in poetry. He stood as an emblem of modern Ireland yet with a voice rooted in the past.

His son spoke at his father's funeral. Though never planned as such, the service became akin to a state funeral and was televised around the world. Mick Heaney told the congregation his father had sent a text only minutes before he had died on the way to the operating theatre.

The recipient had been Marie, his wife of 48 years. It read, in Latin: Noli timere. The words translate as fear not, or be not afraid. It quickly became one of Heaney's most quoted statements.

HomePlace is dedicated to Seamus Heaney. His son says: "The family is very happy to back the project as a memorial to my father... But it's also a community centre which is important"

Mick Heaney is a freelance journalist whose jobs include reviewing radio for the Irish Times.

''You're caught up in the bereavement process. You're in the house dealing with family stuff so you're not keeping an eye on the international media. But an uncle of mine said, 'I don't think you have any idea just what a big deal this is,' and he was right.

"As a family we were outside the conversation. I suppose we knew it would be big on Irish television but then you see it's on the New York Times front page and the scale of the reaction hits home.

"In fact, the massive goodwill towards my father was a big thing in helping us get through the shock - the media didn't get in the way. By and large, people were very respectful and strangely we were buoyed almost."

A few months after the death, the Heaneys were approached by Mid-Ulster Council with the concept which has now become Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy.

"At that stage, neither they nor we were entirely sure what it would be. But the family's very happy to back the project as a memorial to my father and his time living there. But it's also a community centre which is important.

"Early on, we had slight hesitations but what swung it was when they said they would do it on the site of the old RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) barracks. It seemed like a terrific moment of symbolism because in those dark years I remember going up as a kid and it was surrounded by barbed wire and fences."

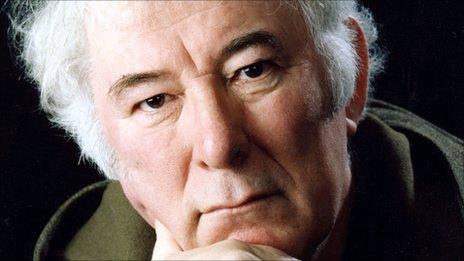

Mick Heaney: "It was my father's persona which helped create the fame he had with the public - it wasn't entirely the poetry itself"

Seamus Heaney was born a Northern Irish Catholic.

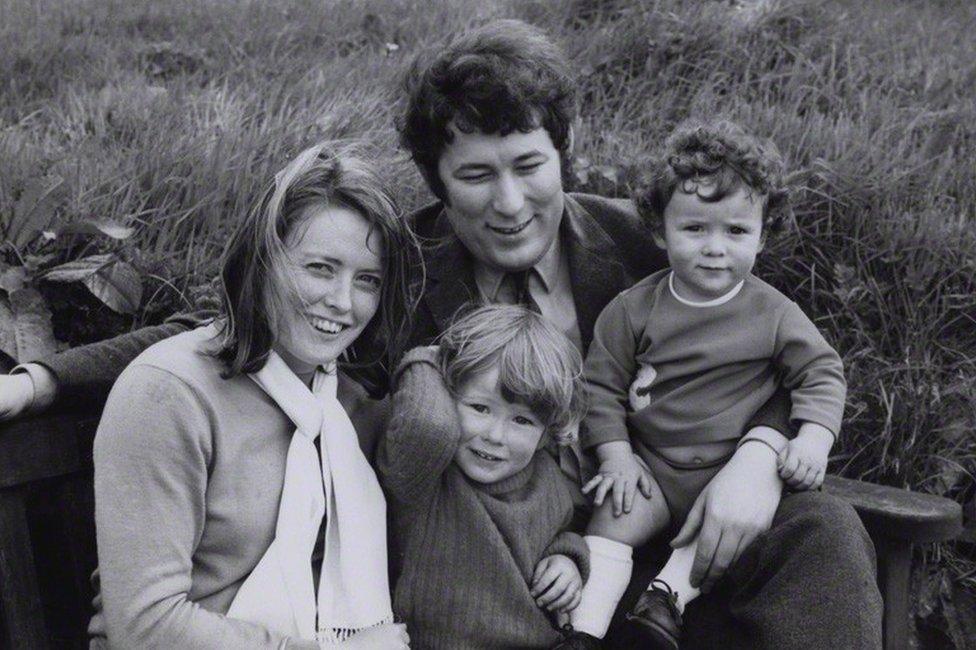

"Dad was a moderate Irish Nationalist and in 1972 he moved to live in the Republic. Certainly that was partly because those years saw some of the worst of the violence in the North: he had a young family to look after but he also wanted to be a full-time writer. So, he moved from Queen's University Belfast to County Wicklow, south of Dublin."

After four years near the village of Ashford, the family moved to Dublin. By then, Seamus Heaney was starting to build a reputation in America and from the 1980s, he would spend part of each year teaching at Harvard.

His son recalls the controversy when, in 1982, his father wrote some lines to protest at being included in the Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry: "Be advised my passport's green/No glass of ours was ever raised/To toast the Queen."

But Mick says with a smile: "And then about 30 years later, the Queen did come to Ireland and my father was invited and they sat at the same table. I understand he got on well with the Duke of Edinburgh next to him.

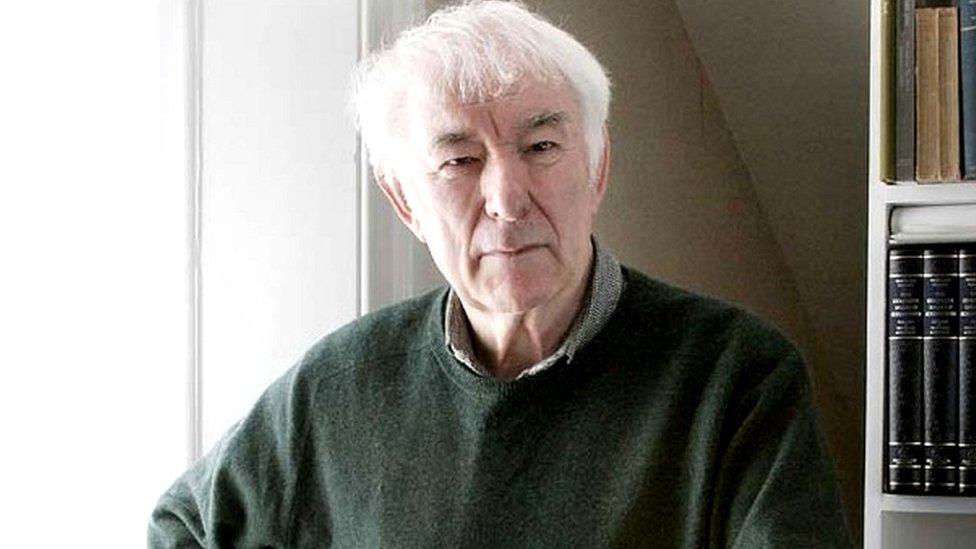

Mick Heaney says he regrets that he didn't read his father's verse more when he was younger

"I always thought it was my father's persona which helped create the fame he had with the public - it wasn't entirely the poetry itself. For one thing, he recorded so much of his verse for RTE and the BBC and he read it beautifully and people loved the voice. I don't think it's only because he was my father that I think no-one has ever read his verse as well as he did. His delivery and pitch were perfect."

Mick says in many ways he and his brother and sister had a normal childhood in Dublin. "Mainly poetry is not a lucrative profession and you have to remember that dad was a teacher, even if when I was a teenager it was mainly in America.

"So, it was a suburban middle-class Dublin background - totally different from the farming community he was born into. There was nothing bohemian about our life. I think in my 20s I finally realised how hard dad worked. You'd go out in the morning just as he was heading up to his office to write and when you came back last thing he was still up there working. But it was a settled, happy home."

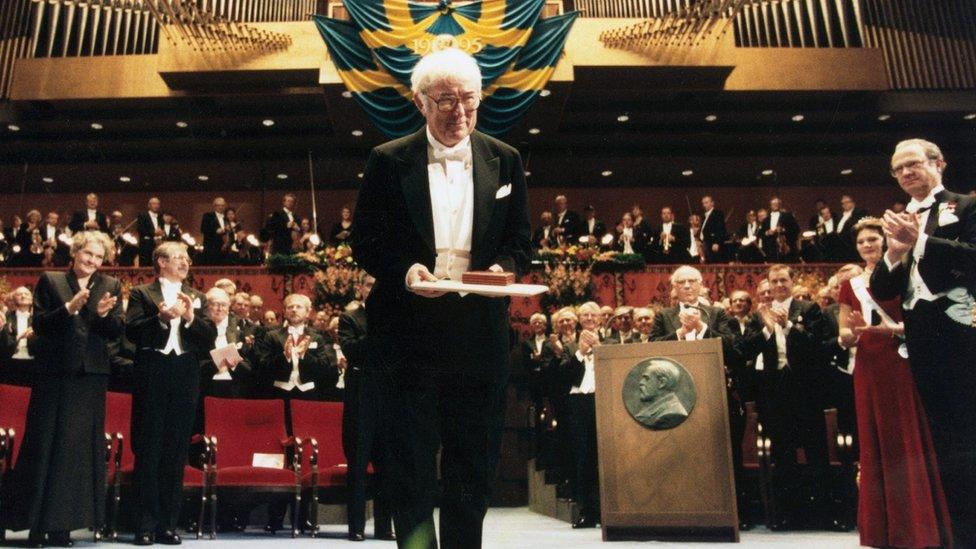

Mick Heaney says of his Nobel laureate father: "I'm sure he knew he had a gift but he didn't take it for granted"

Mick acknowledges that when in 1995 his father won the Nobel Prize for Literature, life changed.

"It was a massive thing and probably all these years later we wouldn't be having the Bellaghy centre if he weren't a Nobel laureate. Though dad was a bit nervous: he knew there is a degree of chance to getting it and the Nobel could have set him up for a bigger fall too. But his hard work meant he survived the sudden success pretty well. I'm sure he knew he had a gift but he didn't take it for granted."

Mick says he regrets that he didn't read his father's verse more when he was younger.

"I suppose because he was my father it was difficult. But I would love to have read some and said to him, 'Oh they're great.' It was mainly my mother who gave him feedback. But I read the poetry more now: I realise that he was more extraordinary than we knew.

"Dublin was a place to raise the family but the places he loved were Wicklow and the North where he grew up. In fact, he later bought the house in County Wicklow which we rented in the 1970s and he would go there and write.

"But the North remained the wellspring for him. It shaped his vocabulary and it was the centre of his creative voice. So it's right we're to have this fine new monument to him there."

Follow us on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, on Instagram, external, or if you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published30 August 2013

- Published30 August 2013

- Published26 October 2013