Robert Rauschenberg: Art pioneer and inspiration

- Published

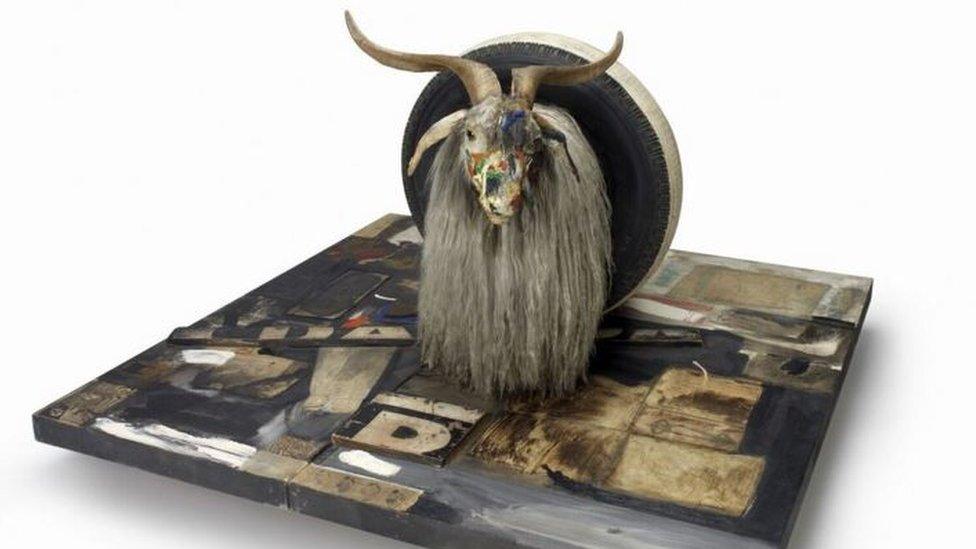

Years before the arrival of Damien Hirst, Rauschenberg had seen the artistic possibilities of the dead animal

Robert Rauschenberg produced some of the most distinctive American art of the second half of the 20th Century. Yet he was the most restless of artists - moving from traditional painting to print-making and sculpture. He was one of the first people to explore the relationship between art and technology. Tate Modern is staging the first major retrospective since Rauschenberg died in 2008.

Years before Damien Hirst first successfully split the cow, Rauschenberg used a full-sized angora goat in his 1955 work Monogram. The goat had once graced a textile company in New York which specialised in mohair. Yet Rauschenberg spotted its artistic possibilities.

Six decades on, the goat greets visitors to the Tate's new show, still apparently oblivious to the car tyre which has somehow wedged around its middle.

Also in 1955 the artist created Bed, a characteristic Rauschenberg "combine". Taking a pillow, a sheet and a quilt he merged them with a traditional oil-painting.

Years later Tracey Emin would go a stage further with My Bed, throwing in her mattress - but not until 1998.

Rauschenberg "was always very serious about work but light-hearted in his engagement with other people", says senior curator David White at the Rauschenberg Foundation

Walking around Tate Modern's retrospective of the work of Rauschenberg (1925 - 2008) these are not the only cases where you think: "He got there first."

Rauschenberg was Texan and was born into a family with a deep Christian faith. At 18 he was drafted into the US Navy and served as a medical orderly.

Post-war he went to Paris to study art but disliked it. "Right place, wrong time," he observed. He returned to America. He was gay but nonetheless was married to a woman for three years from 1950.

'Long road to travel'

David White is senior curator at the Rauschenberg Foundation. He's in London for the new show, which next May will travel to New York.

"In 1965 when I first met Bob you immediately saw he was outgoing and open and convivial. He was always very serious about work but light-hearted in his engagement with other people.

"At the same time he was concerned about the human condition and wanted to help right wrongs. But unlike some artists he was full of enthusiasm rather than gloom."

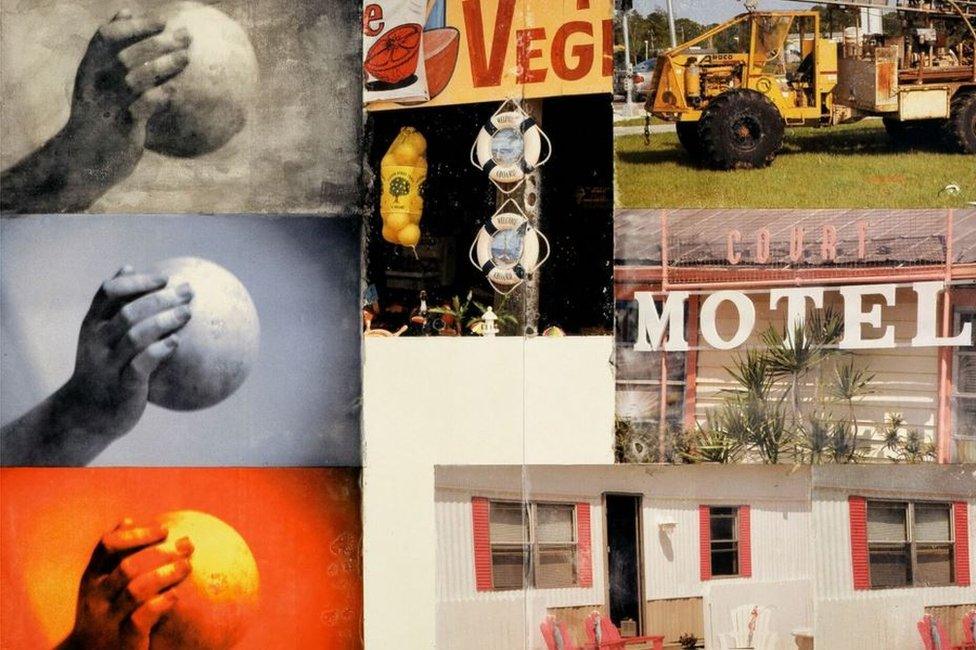

Works such as a Triathlon have led some to class Rauschenberg as a pop artist

White adds: "In 1964 he had won at the Venice Biennale - so he was aware he was esteemed. He was entering the mid-part of his career and finally making money.

"But he still had a long road to travel and so much to explore."

White points out a huge and extraordinary piece from 1966 called Mud Muse.

A metal and glass tank, roughly three metres by four, is filled with soft bentonite clay which bubbles and pops as compressed air passes through. White says it's a good example of how Rauschenberg liked to work.

'His own artist'

"Bob genuinely loved collaboration. It might be with another artist or with people in the theatre or with a choreographer like Merce Cunningham - but with Mud Muse he collaborated with a bunch of engineers to produce something unique. It's serious art - but also it's a comic, delightful, playful object."

White can see why some pieces in the show get Rauschenberg labelled as part of pop art - pieces such as Triathlon or the well-known Retroactive II, which uses an image of President John F Kennedy and, like many Rauschenberg images, came from a magazine or newspaper.

"But the label's really not accurate. Bob came after abstract expressionism, which had dominated American art after World War Two and he provides a partial link from there to pop art. He was his own artist."

"What he shared with the Abstract Expressionists was their ambition and heroic scale," says Tate curator Achim Borchardt-Hume about Rauschenberg

The curator of the exhibition for the Tate is Achim Borchardt-Hume.

"In many ways the turning-point for Robert was after Paris at Black Mountain College (near Asheville in North Carolina). Black Mountain was a true laboratory - students were encouraged to work across many different disciplines. I suspect the parties were as important as classes - but there was also a very strong sense of discipline and of working out what you were good at," says Borchardt-Hume.

"In terms of race or gender or sexuality or religion it was a wonderful mix of everything. And that's extraordinary given that at the time the area beyond the college was highly segregated."

When Rauschenberg moved to a studio in Fulton Street in Lower Manhattan he had little money.

'Nothing he wouldn't try'

"What he shared with the abstract expressionists was their ambition and heroic scale. So though he was younger than them, there's certainly a link," Borchardt-Hume says.

"But he was never happy working in a single medium - there was almost nothing he wouldn't try.

"When he was young he had been very shy and always felt he was a disappointment to his father. His sexuality must have been difficult, given his family background.

"It seems his first relief from shyness was to go dancing. Marriage came early and it failed. But it produced a son, Christopher - now a photographer - and he remained friends with his wife Susan Weil.

"Robert Rauschenberg was rather a political artist. Don't forget that he became a well-known name in the Sixties, with America changing around him. So his work often contains - quite literally - images from news magazines. They might be of Martin Luther King or an Army helicopter but they're redolent of the America he knew."

Tate curator Achim Borchardt-Hume says there are huge riches on display in the exhibition

He adds: "He thought that to be an artist was to play a role in the world. That and his early shyness may be why he was unusually keen on collaborating: he didn't believe being an artist meant leading a life of isolation."

Borchardt-Hume says there are huge riches on display in the exhibition. But he's happy if the image of the Goat in the Tyre dominates how some visitors react.

"It's one of those extraordinary moments where you think, 'how on earth did an artist arrive at this idea?'. Now, with everything that has happened in art since, we think it's quite all right. But I think at the time it must have seemed truly shocking."

The Robert Rauschenberg exhibition runs at Tate Modern until 2 April and then at MoMA in New York from 21 May 2017.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published30 November 2016