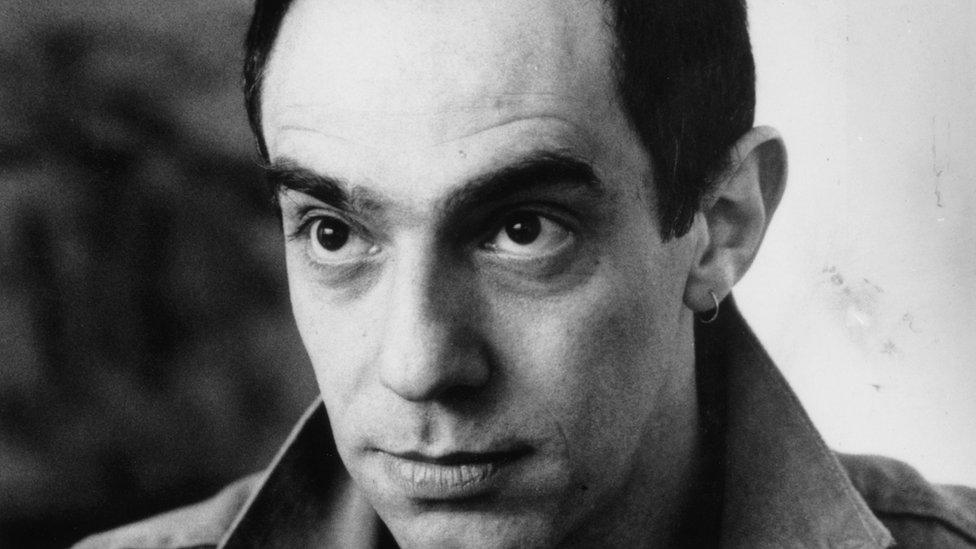

Director Derek Jarman remembered, 40 years after his controversial debut

- Published

In 1976, director Derek Jarman's debut feature film Sebastiane prompted newspaper outrage with its plentiful nudity, gay Roman soldiers and Latin dialogue. Jarman was one of Britain's boldest directors - and his partner says he would have adored the freedom of modern film-making.

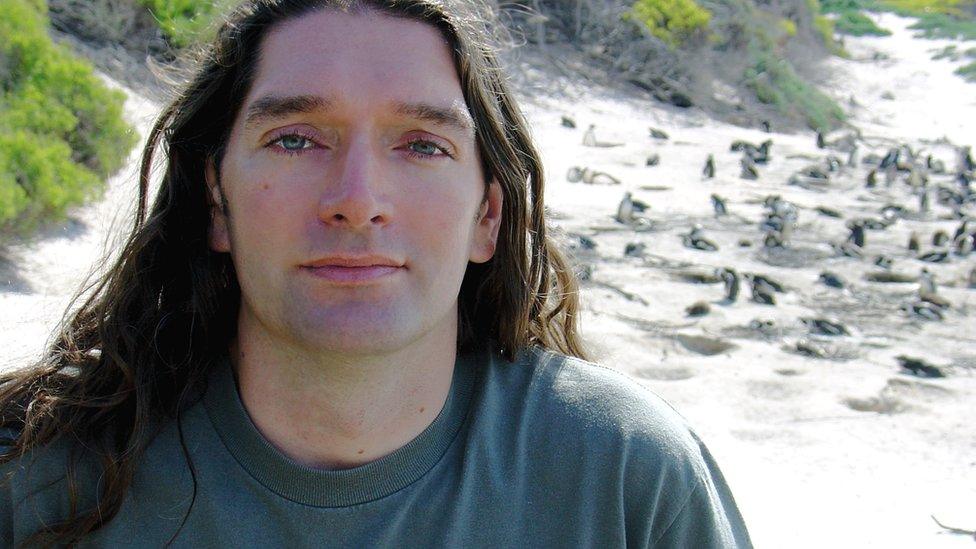

Keith Collins caught Derek Jarman's eye in 1986 at a festival of gay and lesbian cinema in Newcastle. Jarman was instantly smitten with the much younger computer programmer, then employed on secret Ministry of Defence projects.

"I'd gone with a gang of mates to see Gus Van Sant's Mala Noche and Wieland Speck's film Westler," Collins recalls.

"Until then Derek's movies had passed me by or maybe they just hadn't been screened in the north east. So I went to the screening of Sebastiane: I thought it was really strange and I remember I didn't find it sexy in any way."

It had already been a decade since Jarman had released his homoerotic vision of the life and death of St Sebastian, shot on a rocky bit of Sardinian coast.

The budget had only been £30,000 but the film brought acclaim from audiences who knew nothing of Jarman's early career as a designer and painter.

Collins was in a relationship for eight years up until Jarman's death in 1994

There were critics who thought Jarman had a talent for imagery but was never capable of creating a coherent storyline. Yet in 1978 he had success with the punk-filled Jubilee and a year later came his version of Shakespeare's The Tempest.

By the mid-80s, Jarman was living in a tiny flat above the Phoenix Theatre on the Charing Cross Road in London. It was only 4.5 metres by 5.5 metres - but he decided it would be a good idea for Collins to join him there.

"Out of nowhere I got a letter from Derek. He'd got my name and address from the festival director. But I wasn't interested and I made that very clear in my reply - several replies in fact.

"Derek wouldn't give up - but the festival director advised me not to go to London because he said Derek was into S&M and I'd end up in some dark dungeon somewhere.

'Head over heels'

"Finally I decided to go anyway. When I phoned Derek I asked what he was doing and he said he was painting - which on Tyneside meant painting and decorating. When he mentioned that there was black paint everywhere I thought all the talk about the dungeon must be true.

Swinton 'had an astonishing psychic rapport' with Jarman

"Actually it turned out Derek was working on submissions for the 1986 Turner Prize, which featured a lot of black paint."

Gilbert and George won the Turner, but 1986 did bring Jarman the man who would stay with him for the rest of his life and who did more than anyone to keep him alive in the tough final years.

Collins says it was never a standard relationship. "When I arrived at the flat in London, I went to kiss Derek and he stopped me. He said that since we'd first met he'd been diagnosed as HIV positive and that he didn't think we should have a physical relationship. People were still learning about Aids.

"But my short stay in the flat became permanent, and before long I was head over heels in love with him. I gave up my career writing military software. I always knew Derek and I would get on - we had a very similar sense of humour and shared a sense of what's important in the world."

'Real rebel'

At about this time, Jarman became headline news again. Partly it was the release of the film Caravaggio, featuring Sean Bean and Tilda Swinton, which some regard as his most accomplished film.

But also Channel 4 had shown Sebastiane and Jubilee, which outraged parts of the press as well as the anti-pornography campaigner Mary Whitehouse.

Jarman seldom turned down an interview, and from the late 1980s he was almost as well-known for his campaigning as for making films. He was critical of what he saw as a slow official response to the Aids crisis. And he was furious at new legislation in 1988 known as Section 28, designed to stop local authorities promoting homosexuality.

In 1990, he spoke openly on Radio 4's In the Psychiatrist's Chair programme about his HIV status - one of the first well-known people to do so at a time when Aids was a topic still surrounded by ignorance and fear.

Actor Karl Johnson appeared in three Jarman films and came to know him well.

"When I first met Derek it was on Jubilee. He would say things like, 'I know nothing about acting and really I don't know very much about films.'"

'Terrible blow'

"But he had a wonderful charm and if you're an actor that kind of statement emboldens you - he made you dig into yourself. And he had a rare talent for finding the right people for the film in all departments.

"I was happy to be working with a real rebel - he was sort of a grown-up hyperactive Christopher Robin type of character, with endless enthusiasm and energy. That was what attracted him to punk as a topic - Jubilee was like animated graffiti on film.

"When I first knew him he seemed very apolitical. But as he got older he became more and more political. He hated Margaret Thatcher and would bring it into interviews whenever he could. His films were cheap to make so he had total freedom - they sought no-one's approval."

Collins is careful to point out that life with Derek could be hugely entertaining almost up to his death in February 1994.

"His being HIV positive didn't dominate everything every day for the eight years I was with him.

"There was the glorious day when we were with Tilda Swinton, an actress he had an astonishing psychic rapport with, and we were looking for bluebell woods in Kent as a filming location.

"Near the coast at Dungeness we passed this wooden house, which Derek had already spotted on another shoot and when we stopped outside it was for sale.

"The owner Peggy had an extraordinary voice like she'd been dialect coach to the Daleks. When Tilda asked if Peggy didn't mind being almost next door to a nuclear power station, she croaked 'Me and my husband have lived here 30 years and it ain't affected us.'"

"We had coughing fits to disguise the laughter. But life with Derek was filled with funny moments."

From 1987, Derek Jarman lived partly at Prospect Cottage, looking out on the English Channel, and partly in London. From about 1990, his health began to decline and increasing amounts of Collins's life were taken up with duties as carer.

"There are so many people who give up much of their lives to care for friends or relatives who are sick - it was never just me. And society doesn't really value the sacrifice because wiping someone's bum isn't exactly fun or glamorous.

"Virtually to the end Derek was still working on new projects. There were always good times but Derek was fiercely independent and becoming more ill was a terrible blow to him.

"Of course Derek wasn't the only one. I was around people - writers and painters and musicians - and I thought I am going to spend the rest of my life with you people: there will be so much fun and life and mischief always. And then they're gone."

Collins says Jarman thought it was his responsibility to talk publicly about his HIV status.

"And for a film director that was perilous because you need insurance to start a film in case you die or are incapacitated. But people wanted him to keep working and somehow he got through."

Collins says it's a great sadness that Derek Jarman died before a new generation of technology could take him in fresh artistic directions.

"Even just that whole films are now made on people's phones - Derek would have adored that. Collaboration with actors and musicians and writers could have become easier.

"And digital distribution would have made things so much quicker and cheaper. Derek was only 52 when he died - we were robbed of so much more he should have done."

Witness: Derek Jarman was broadcast on the BBC World Service, on Tuesday 20 December - listen to it on BBC iPlayer Radio.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published10 August 2015