What is the function of an editor?

- Published

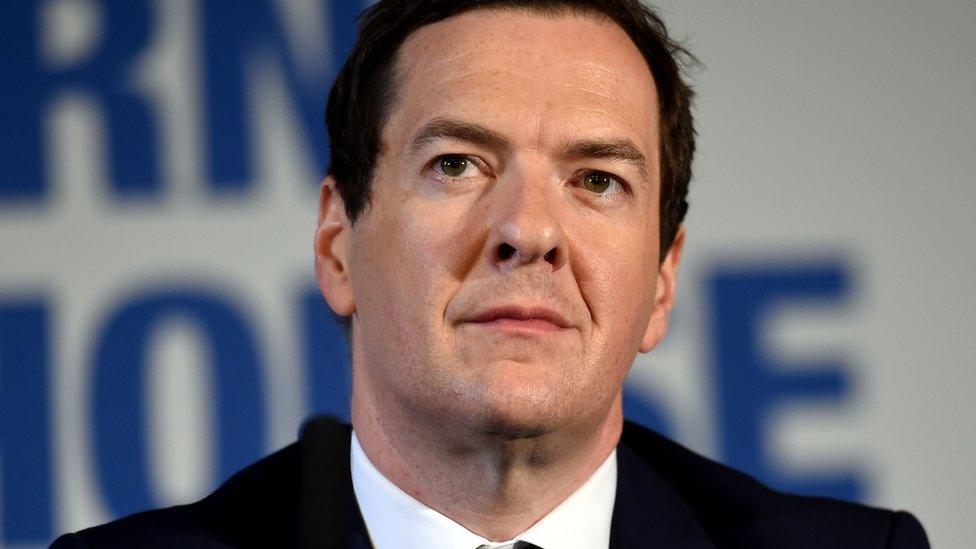

George Osborne will take over as editor of the London Evening Standard

Editing a newspaper is an extremely rewarding and tough job, probably harder these days than a few decades ago, because of scarcity of resources and the demands of the internet.

But being an editor isn't just an editorial job.

The editorial side of it is the most fulfilling and intellectually stimulating part, but it is only a part.

There are also huge commercial responsibilities - how do we make money and save money? - and leadership and management duties.

Leadership is about creating a moral vision for where you want to take a team; management is the daily activity of getting them there.

It has always seemed to me that in rich newspapers, the editor gets to focus on editing, while other people think about the commercial and managerial side of it.

For instance, the Daily Mail has several busy managing editors, whereas the Evening Standard has only one.

George Osborne to become Standard editor

Osborne Evening Standard job prompts call for inquiry

George Osborne: From history buff to austerity editor

At organisations that are strapped for cash - and the Standard is facing big commercial challenges - editors have to spend relatively more of their time thinking about commercial and managerial obligations.

And all of that is hugely time consuming. It leaves less time than you would like for the really exciting bit: editing.

Truth, integrity and reputation

Editing is an exercise in selection and judgement: what to put in and - just as important - what to leave out.

Which pictures, campaigns, and above all stories to run? What's the best headline on that front page splash? Shall we give this or that person a kicking in the sports pages? And should our cartoonist really depict Nigel Farage as an amphibian yet again?

When making these decisions, based on your judgement, which is in turn informed by your values and experience, an editor has three sacred loyalties - in my view, in no particular order.

First, to the truth; second, to the reader; and third, to the integrity and reputation of the newspaper.

Some would argue that there are other loyalties.

An editor of The Catholic Herald might think they had a duty to God, for instance; an editor of Country Life might feel they had a duty to England's enchanted land; and all editors are likely to feel a duty to those paying the bills.

But those earlier loyalties are supreme.

They are very different to the loyalties required by political parties.

I have never been a member of a political party, but I suspect those who have would say their loyalties aren't primarily to truth, readers, or newspaper reputations.

A political party is an institution that organises its members to acquire and exercise legislative power.

Its members have loyalty above all to that task. If they are committed, they wake up every day thirsting for power.

Once they have acquired it, fidelity to their tribe makes them determined not to relinquish it.

Quite aside from the sheer practical workload, it is not easy to see how the loyalties required by editorship and the loyalties required by membership of a political party can be reconciled.

The latter long to inhabit the corridors of power. The former want to throw grenades at it.

Divided loyalties

Journalism, at its best, is about the ferocious scrutiny of power.

That requires a certain distance from it. Of course, there are different types of journalism.

I can see how it might be feasible for a theatre critic to be group secretary of his local Socialist Workers Party.

I can also see how a brilliant football correspondent could be a member of the neo-Nazis.

But an editor, who has to conduct daily combat with politicians?

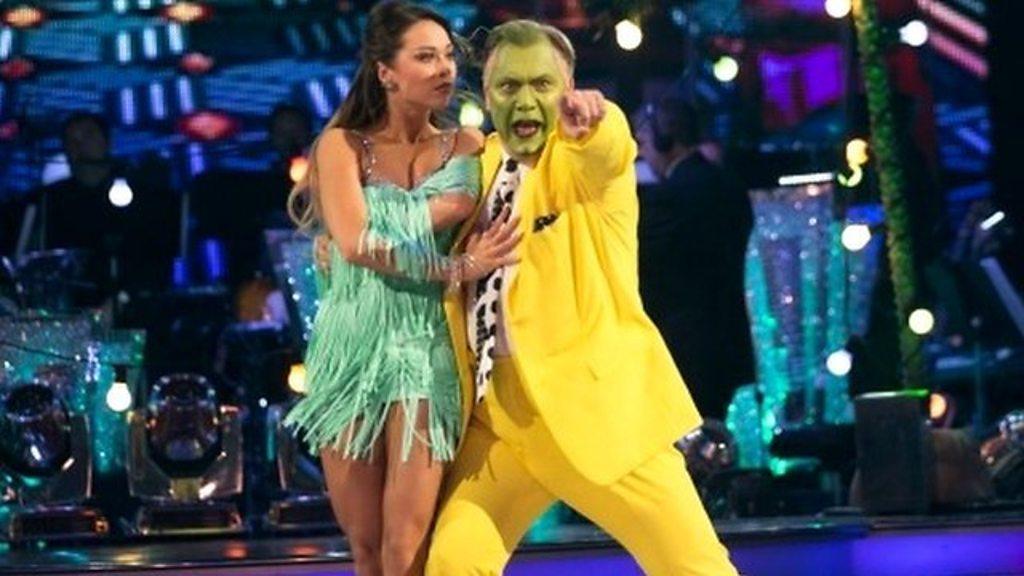

In being a member of the Conservative Party and, soon, editor of the London Evening Standard, George Osborne faces both practical and philosophical problems.

The practical one is when to sleep. The philosophical one is how to reconcile his clearly divided loyalties.

Which of his constituents matter most - those in Tatton, or his near-million readers at the Standard?

How does he cover, say, a Budget: as a loyal Conservative MP, or as a fearless editor?

It is hard enough to see how you reconcile being a member of a political party with being a journalist, let alone being an editor.

However, being not only a member of a political party, but a sitting MP and a recent chancellor, as well as someone who retains political ambitions, is much tougher still.

And that's before we even consider BlackRock. How can you cover the world of asset management while being paid £650,000 by it?

The idea that Mr Osborne could recuse himself from stories about that industry, or indeed the City pages altogether, strikes me as sub-optimal, to put it mildly: it would be bizarre to have a former chancellor as editor, only for him to have no involvement in business coverage.

Full-time job

These conflicts of interest are untenable, and so - as I said on Friday - I can't see it lasting.

Given his sources of income, he's much likelier to give up being an MP before he gives up having lunch at BlackRock.

Whether it happens when Tatton disappears as a constituency, or before, I suspect he will be editor of the London Evening Standard after he is an MP in Cheshire.

As I mentioned in my previous posts, his task at the paper - setting out a clear strategy, improving the product, raising its profile, and turning the business around by finding new revenue streams - is one for which he has relevant experience and connections.

That said, it strikes me as a full-time job. Perhaps, therefore, Osborne hasn't fully grasped the function of an editor.

I hope this post helps.

- Published18 March 2017

- Published17 March 2017

- Published17 March 2017

- Published17 March 2017