Introducing… The Russell Prize 2017

- Published

Philosopher, mathematician, Nobel Prize winner - and masterful prose craftsman: Bertrand Russell in 1962 on his 90th birthday

I'm thrilled to introduce licence fee payers to a new prize and ceremony, because goodness knows we need more of them.

The Russell Prize, which in 2017 celebrates its inauguration, is named after my hero, Bertrand Russell.

These awards celebrate journalism and writing that honours the intellectual and moral virtues Russell's prose exemplified. Before explaining what those virtues were, let me admit I am shamelessly pilfering an idea colonised by David Brooks of the New York Times, whose Sidney Awards, external are always a pleasure to read.

Given that wisdom begins with the realisation that original ideas are over-rated, I make no apology for that.

Let me also add that the recipients of these awards have been through a rigorous selection process: they were submitted, by me, to a discerning and impartial selection panel comprised of one member, also me, where I am honoured to hold the title of founder, convenor, president and chair.

So anyone who says this blog post, indeed this entire ceremony, is just an excuse for me to re-up my favourite bits of writing this year is completely wrong.

A trinity of virtues

I used my influence in the panel to ensure the Russell Awards truly reflect the eccentric greatness of Bertrand Russell's prose, which in my view was the finest of any craftsman (or craftswoman) writing in English in the 20th Century.

Like all the finest prose writers, he combined three qualities.

First, plain language, resulting from clarity of thought and diction. Not all George Orwell's rules about how to write are worth living by, but his warning against the dangers of inflated prose was vital, and it is true that it takes real guts to use plain English. Cowards conceal themselves in verbosity. Using simple language is a mark of courage.

Second, pertinent erudition. Erudition is a virtue, but it is often redundant, and most valuable when apposite. For instance, I am (ahem) close to erudite about the varieties of thumb-generated back-spinners used, mainly, by Australian bowlers such as my other hero Clarrie Grimmett in the inter-war years. But that's not much use in an article on, say, why Rupert Murdoch has sold up to Disney. (Both, I suppose, are spin doctors of a kind). Deep scholarship and learning is wonderful to read, if applied with a light touch, and pertinent.

Third, moral force, especially through an instinctive and visceral revulsion at injustice. Naturally the greatest writing has a kind of ethical energy about it. Who wants to read leaden, plodding prose that equivocates so meekly it leaves you feeling like you've just come off a see-saw?

Very, very few writers are able to combine these three virtues consistently. In the 20th Century, only Orwell also managed it, and The Orwell Awards were taken.

Tzvetan Todorov, Susan Sontag, Isaiah Berlin, Martha Gelhorn, Ernest Hemingway and Michael Oakeshott touched these heights at times. Christopher Hitchens had erudition and moral force in abundance but little interest in plain English.

In our time, the only writers whose work I know well, and who have a claim to be in this sort of company, are Roger Scruton, John Gray, David Runciman and Ta-Nehisi Coates. Of those who I know less well, it strikes me that Hilary Mantel (for her prose in the London Review of Books), John Lanchester, Andrew O'Hagan, Zadie Smith and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie are clearly very special.

But that lot have had plaudits aplenty.

So let's honour other writers who are keeping the trinity of virtues Russell exemplified alive.

I'm delighted to announce that the winner of this year's Russell Award is…

Ronan Farrow, New Yorker: 'Harvey Weinstein's Army of Spies', external

It's not often a reported essay can be said to shift a culture, turbo-charge (and arguably launch) a global movement, bring down a mogul, and overturn sickening injustice perpetrated for decades, potentially leading to multiple jail sentences - but that's what Farrow's remarkable work achieved.

Ronan Farrow: His Harvey Weinstein story for the New Yorker magazine is a remarkable work of journalism

Deeply reported, and displaying the tenacity and sensitivity to encourage brave women to trust him, his article is already and rightly the stuff of legend.

And how about this as a lesson for wannabe journalists: the story was rejected when he first took it to bosses at NBC. So another virtue of this inaugural winner of The Russell Prize is that it has shown a generation of young journalists the value of persistence, and backing yourself to take on the mighty.

When I consulted the judges, they felt the other candidates were all so strong that they should be jointly declared runners-up.

So in no particular order of merit, here are the recipients of the runners-up Russell Awards for 2017...

1. Sarah O'Connor, Financial Times: 'On the Edge', external

Everyone now says globalisation is failing millions of people in the rich world. A related phenomenon is de-industrialisation: the collapse of industries away from capital cities and metropolises that had once held communities together, and given workers a sense of dignity and purpose. But taking this story from the realm of dry economics to a place of real human suffering isn't easy.

Sarah O'Connor's cover article for the Financial Times magazine tells the story of de-industrialisation in Britain's coastal areas through an epidemic of mental health problems

In a magazine cover article, Sarah O'Connor did just that, telling the story of de-industrialisation in Britain's coastal areas - and specifically Blackpool - through an epidemic of mental health problems. It was hugely readable, urgent, packed with big ideas and told an essential story very well. Whoever came up with the headline 'On the Edge' for the magazine cover deserves a pay rise. Russell would have approved (of the pun, not the pay rise - though maybe both).

2. Stephen Bush, New Statesman: 'On the Tube, I saw the father I'd never met', external

Bush's piece, published just this week and about why he didn't say hello to his father when given the opportunity, went viral in an unusual way. When I looked it up online, I was taken aback by the number of people who said they had been in a similar situation, or made a similar decision.

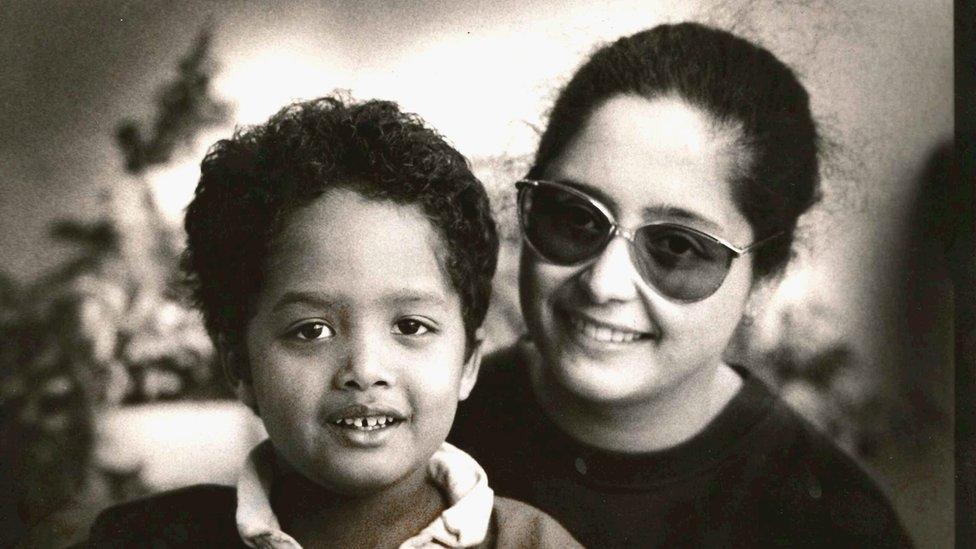

Stephen Bush as a six-year-old, with his mother Rachma Bush

I thought that what took it remarkable heights wasn't just the moving nature of the story, but the chatter high up in the piece about how digital technology has changed the options available for unconventional families today. Above all, there was a strong authorial voice, despite the simplicity of the prose, which had a reductive, distilled quality. Russell would have approved.

3. Ross Douthat, New York Times: 'The Crisis for Liberalism', external

OK, it's true, this was written last November. Strictly speaking, it should have entered last year's competition - but the judges felt that it would be wrong to penalise the writer for their own failure to get organised this time last year.

Douthat's column is a defining columnar critique of liberalism, and where it has gone wrong, in the aftermath of Brexit and Trump - and not just because it takes, to an exquisite apogee, themes I've been trying to articulate for a decade. Douthat grasps the fact that the demoralisation of liberalism followed inevitably the de-moralisation of liberalism.

Ross Douthat: His New York Times article from the end of 2016 is a defining critique of liberalism post Brexit and Trump

As Douthat sees it, the 20th Century was a triumph for the ideology of freedom; but civilised societies need more than freedom. They need deeper forms of human association; they need to create a sense of belonging and membership, and - in his view - liberals had left those behind. For writing the one piece you had to read in the wake of Trump and Brexit, the judges were delighted to recognise this article, despite its falling outside the parameters of the competition.

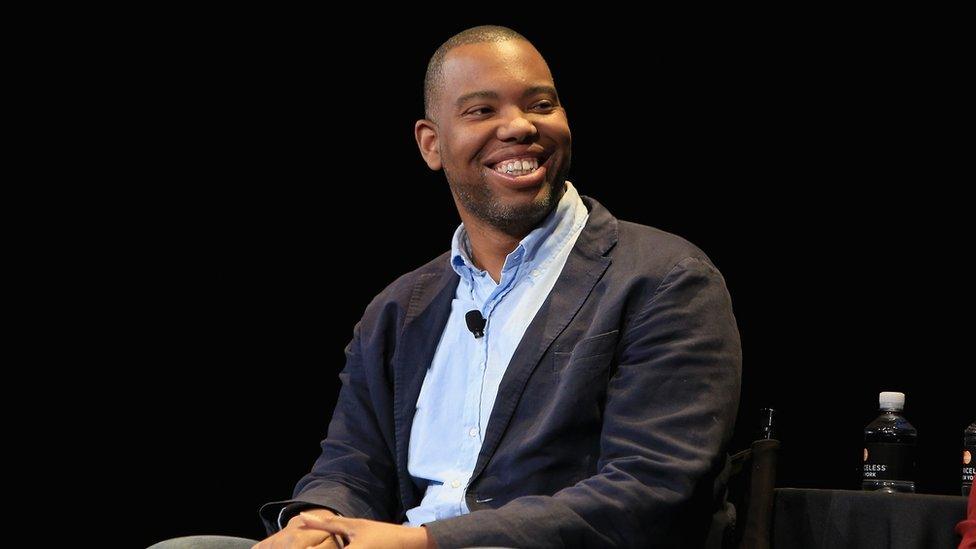

4. Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Atlantic: 'My President Was Black', external

Coates's work is very challenging, not because he uses difficult language or particularly complex ideas; rather, because his ideas are alluringly simple. In his remarkable books, he sees American history through a clear prism, and has such powerful ideas - for instance, that America is built on the destruction of black bodies - that to read him is to feel in the company of a uniquely articulate champion of the oppressed.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Challenging writing

It doesn't always feel like he gives due consideration, let alone weight, to alternative points of view; but then that's not really his style. He has become a troubadour not of Black America, but Democrat America, and his exhaustive reflection on the Obama years makes sense of that presidency from a very particular, and very valuable, perspective. In favouring words with fewer syllables over more, Coates has done his bit to revive the idea that plain language is a weapon, too.

That concludes this year's awards ceremony.

The judges are delighted that the inaugural recipients of The Russell Prize and runners-up awards should obtain such high standards, and commend the runners-up for their outstanding work.

Entries for the 2018 competition open on 1 January.

May plain prose and erudition long outlast the injustices our esteemed winners have sought to vanquish.