Media: What to look out for in 2018

- Published

When I composed a blog post around about this time last year, on trends to look out for in the media in 2017, I mostly eschewed concrete predictions.

And thank goodness. Who on earth could have foreseen a snap general election in which social media would drive a shock result, Rupert Murdoch selling up most of his company to Disney, or the BBC getting a new director of news and current affairs?

Then again, some of the trends in media are so well established that it is possible to make an informed guess as to what is around the corner. So forgive me again, would you, if I don my helmet and shield and venture forth into this lookahead to 2018...

1. Tech and the intellectual trap

Of course the backlash against big tech companies will intensify in the coming year. Many of those who have led the charge against, for example, Google and Facebook, are publishers with a strong commercial incentive to do so, because those two companies are taking their advertising dollars. That is not to invalidate the stories, of course.

But if they continue then so, too, will the entrapment of this whole debate in a language and intellectual prism which is out of date. All the calls for regulation and social control of these companies are happening within a framework for media - whether legal, social, or moral - which is simply not suitable for these companies.

For instance, the exhausted debate about whether they are platforms or publishers ought to move on to a sober acceptance that they are new kinds of companies, with huge variations between them, which have characteristics of both platforms and publishers.

I'll try to do my bit on this, but I suspect tech will remain trapped in a conversation that hasn't kept pace with the times.

2. Advertising will continue to fold into just two companies

Estimates for the proportion of digital advertising dollars consumed by Facebook and Google vary, but that it is growing sharply is not in any doubt. On current trends, it is quite possible that by the end of 2018, 90 per cent of new digital advertising spend in the US goes to these two giants.

The tech giants are devouring digital advertising dollars - at a cost to the advertising industry

Can you guess what that means for the advertising industry, which employs millions of people, many of them hugely creative? In many cases, it means a P45. Obviously there has, historically, been a demand for agencies to tell clients (i.e. wealthy brands) where to spend their money, and how best to communicate that message by crafting a savvy campaign.

Increasingly, however, the first half of that equation is becoming simpler, because you just spend your marketing cash with Google and Facebook. This will drive innovation: you may have noticed the adverts in your Facebook news feed are eerily well-informed on your correspondence with friends and family, your general interests, and even recent holidays.

And yet, for all that, these companies are often far from transparent about just who is consuming content and where.

2018, like 2017, is going to be a very tricky year for many chief marketing officers at big companies, and for many advertisers full stop.

3. TV will bifurcate

Television is splitting into two, between high-end entertainment with big production values, ranging from glamorous dramas to documentaries and boxset comedies, on the one hand, and live, event-based news and sport on the other.

If Murdoch is selling most of his $80bn company because he thinks it is too small to compete in entertainment, what is the future for other media organisations?

I have been told by someone senior on Planet Murdoch that the reason Rupert decided to sell most of his entertainment interests to Disney is because he could see this bifurcation happening, and he realised that to compete in the entertainment game you need massive scale and as direct a route to customers as possible.

Even he, the ultimate media mogul, can't compete with the likes of Netflix, Amazon and Disney when it comes to entertainment, so he's focusing on what he knows, which is news and sport.

This is what he meant when he said the deal with Disney means he is "pivoting at a pivotal time".

This bifurcation does rather beg the question of what role all the stuff in the middle - those lower production value shows, broadcast on TV channels that are a middle man between programme and viewer - will play. If demand from viewers for such shows begins to dry up, the whole industry will face upheaval.

4. The need for scale will drive consolidation

All the mega mergers in media today, from Disney and 21st Century Fox to AT&T and Time Warner, are driven by this need for scale. When you have ferocious competition for eyeballs, you need to own as much of the great content as possible, and have the most direct route to as many customers as possible.

This is what I meant when I wrote last year that pipes will meet ideas. The owners of distribution (pipes) will need to get together with those who have the best ideas, content and stories to captivate consumers. This is called consolidation. It happens most often in sectors where there is an over-supply of providers (as with British newspapers, historically), and where there is technological upheaval.

The tech giants reshaping media - Netflix, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google - all have massive scale. They have customer bases that are hundreds of millions if not billions strong.

Everyone working in media should ask themselves: if Rupert Murdoch thinks that his $80bn company is too small to compete in entertainment, are they working somewhere that has the scale to do so? The BBC, by the way, is about a twentieth of that size.

5. Streaming will continue to make the internet, not television sets, the home of broadcast

The bifurcation of TV and the drive toward scale are driven by technology. Not, that is, merely by the arrival of massive new tech players to the broadcast game; more by the capability of streaming services to broadcast direct to consumers via the internet and, especially, their smartphones. This cuts out those middle men known as TV channels.

In the US, a huge library of streaming services - Hulu, Amazon Prime, YouTube, HBO, Showtime, Starz and many others, long before you get to Netflix - are on offer to consumers, and in 2018 many more UK customers will pay for the freedom and choice they bring.

Two consequences follow: first, a generational divide in consumption, where older viewers continue to watch television sets and allow schedulers to determine their viewing habits; and second, a dawning realisation among British TV executives, reliably late to the game, that the very idea of channels and schedules is becoming obsolete for millions of the most addicted viewers.

It will take many years, perhaps even decades, but the current trends in media suggest that TV channels will become focused on those live events - news and sport - that Rupert Murdoch says he wants to focus on.

6. A major BBC News show or service could shut, prompting outrage

Gone are the days when I would look at weekly figures for revenues, or spreadsheets showing editorial and production costs, and being generally terrified of a P&L, but desperate to see it nevertheless.

So I don't know very much about the breakdown of costs across BBC News. But I do know that around £80m still needs to be found in the next three years or so (the goalposts have been known to shift); and I'm told that Tony Hall, the director general, and Anne Bulford, his deputy, would like to frontload some of those savings.

You do the maths. To find, say, even £20m, you could slice whole chunks out of a range of services. Maybe you could get to £30m with painful but relatively unarguable chops/trims/cuts (delete as appropriate).

But how do you get to £40m, £50m, and more? Only by doing the hard stuff: losing particular programmes or services. This will prove very unpopular, not least because said show or service may employ a producer who has impeccable political connections.

Chopping whole shows or services at the BBC is fiendishly difficult. It always runs into political difficulty, or a non-political lobby group. But as night follows day, the numbers make it plain that some high profile cuts are imminent, and with it, the backlash. This could come as soon as the first quarter of this year.

7. Many companies will wake up to the camera as a way of talking

The genius of Snapchat, though it isn't unique to that platform, is the realisation that for a generation of teenagers and 20-somethings, the camera is a way of talking. That is why Snap Inc call themselves a camera company; it is also why their executives make a point of noting that Snapchat opens to the camera (unlike, say, Twitter or Facebook which open to a news feed).

The camera is now a way of talking. Companies now need to harness this fundamental shift in the use of technology for communication

This is no less than a fundamental shift in the use of technology for communication, and the potential for media is enormous - both in terms of programme-making and advertising.

Many of what you might call the heritage brands in written media, from The Economist to The Daily Telegraph have started making useful inroads on Snapchat. It's a long way from the crafted articles for a newspaper that their staff entered the profession to do, but the chance to connect to a generation of young people is exhilarating.

8. Podcasts will do for the left what talk radio has done for the right

This is already happening of course. It is a curious fact that for years, talk radio in both Britain and America was dominated by the right. Of course, many radio stations served liberal audiences too, but they tended to be a minority.

Now the extraordinary explosion in podcast consumption, particularly among young people, has given liberals an opportunity to counter-attack. This is especially the case in the US, where thousands of podcasts have mobilised and politicised a huge new audience, leading to live shows, merchandising, social solidarity and a resistance movement.

In Britain, there are countless outstanding conservative podcasts. Now for the Left, and particularly those sympathetic to Jeremy Corbyn, podcasts offer an opportunity to consolidate their perceived advantage on social media.

There is no intrinsic reason why podcasts should favour liberals, but the demographics may offer one: younger people may prefer podcasts consumed on smartphone to radio stations, and they are more likely to vote in a leftish manner.

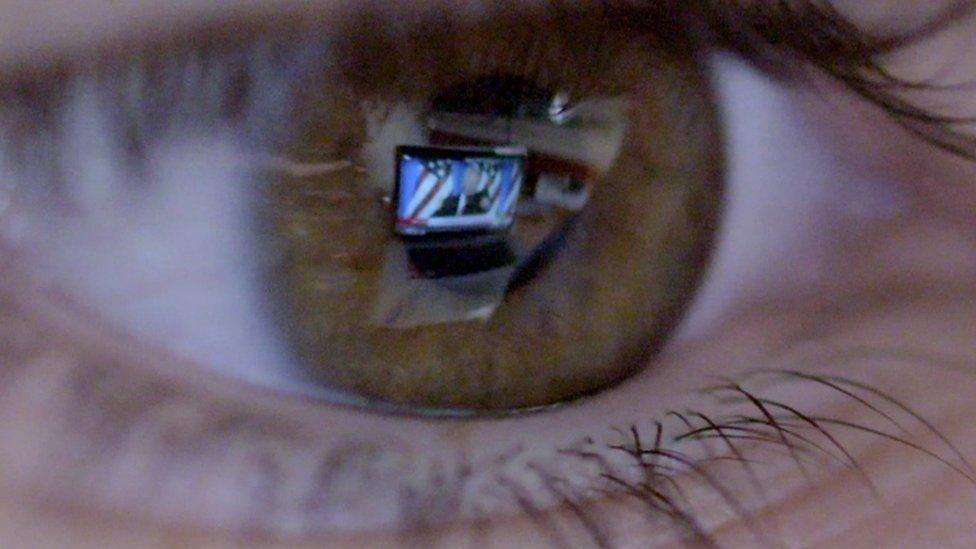

Fake news: 2018 should give a concrete sense of just how big a deal it is

9. Some hard evidence on fake news at last

I've often explained on this blog why I am cautious and sceptical about the fake news phenomenon, and won't repeat those arguments. In 2018, however, we should get a much more concrete sense of just how big a threat fake news is.

In the US, Robert Mueller's investigation into links between Trump and Russia may cast fresh light on the use of bots by those around Vladimir Putin. And in Britain, it would be reasonable to expect - not least after a tense meeting between Boris Johnson and his Russian counterpart last week - for the Prime Minister to put some flesh on the bones of her assertion that Russia is interfering with democratic politics in the UK.

Nevertheless, every time you hear a journalist in what some call the mainstream media bewailing fake news, remember they have an incentive to do so.

10. Might another foreign investor swoop into Fleet Street?

It's inevitable that big changes, including of ownership, are coming in Fleet Street. The Observer gets a new editor soon, perhaps even in January, when The Guardian's switch to tabloid will generate savings in production.

Trinity Mirror is working to merge with rival publisher Express Newspapers

The deal to smash the Express and Mirror titles together will go through, if the companies can work out how to solve their respective pension liability nightmares. With a willing buyer and seller, the deal ought to happen.

If the Barclays have recouped their initial investment on the Telegraph, they could well sell it. Might it go to a foreign investor? Unthinkable in Lord Hartwell's day, but with money to burn and a reputation to burnish, it's certainly possible.