Will Gompertz reviews Charles I: King and Collector ★★★★★

- Published

There really is only one conclusion to come to having seen the Charles I exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, and that is: Oliver Cromwell was an idiot.

I am not referring to his controversial military career, or the role he played in the beheading of the King, but what he did when he led the republican government in 1649.

In an act of extreme religious piety and mean-spirited whitewashing of the previous regime, the great oaf sold off Charles I's magnificent art collection to a disbelieving but gleefully opportunistic continental cohort of rich aristocrats and royal courts.

This is why it is the Prado in Madrid - and not the Royal Collection in London - which owns Titian's fabulous full-length portrait, Charles V with a Dog (1533). It also explains why the Louvre in Paris is home to Anthony van Dyck's superb Charles I in the Hunting Field (1599-1641) and not, as you might expect, Windsor Castle or Hampton Court.

Charles I in the Hunting Field by Anthony van Dyck

They are but two of the hundreds of masterpieces that Charles and his French wife, Henrietta Maria (a Catholic, which would have made Cromwell spit), acquired in a two-decade spending spree informed by their highly educated eye for art.

For more than 350 years, Cromwell's folly - his small-minded money raising exercise the Prado mischievously calls The Sale of the Century - has made it impossible for us to see and enjoy the full extent of the artistic riches that made the Caroline Court the envy of Europe.

Now we can.

Charles I and Henrietta Maria with Prince Charles and Princess Mary by Anthony van Dyck

And that is largely thanks to the good offices of the effervescent Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures, who co-curated the exhibition with Per Rumberg. For it was he who suggested, when asked how best the Royal Academy might celebrate its 250th anniversary, a reunification of Charles I's collection.

It was a good idea, which has been exceptionally well realised. From the first room to the last, the show maintains a coherent, compelling structure, which tells the story of Charles's collecting and collection in clear chronological and thematic episodes.

It starts with the main protagonists.

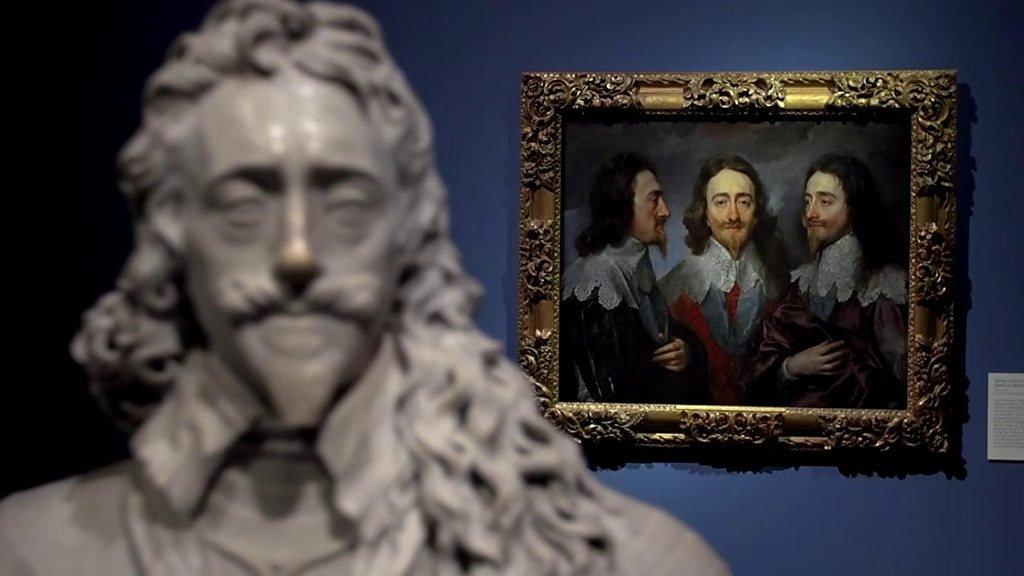

Charles I in Three Positions by Anthony van Dyck

We meet the King head on and in triplicate in Charles I in Three Positions (1635-36), by his artist-in-residence, Anthony van Dyck. The Flemish 'principalle Paynter in Ordenarie to their Majesties' can be seen to the King's left looking conspicuously arty in Self-Portrait with a Sunflower (1633).

On the opposing wall is his portrait of Henrietta Maria (1638) in profile. These three characters are the mainstays of the show.

The story proper starts in the next room, when Charles was a 22-year-old unmarried Prince on the lookout for a suitable bride. He decided to chance his arm and nipped over to Madrid in the hope of making a tactical marriage to the Infanta Maria Anna, sister of Philip IV of Spain. It didn't work out, but he did fall in love.

With art.

The Supper at Emmauss by Titian

He returned with a hoard of tip-top paintings, including the aforementioned Titian, a very good Veronese, and a portrait of himself (now lost) by Philip IV's court painter, a certain Diego Velázquez.

Like a true connoisseur, Charles focussed his collecting. First and foremost there were the pieces produced by Anthony van Dyck, designed to document, celebrate and elevate the King's magnificence. As were the other two areas in which he concentrated his efforts.

The first we encounter is the work of the Dutch, Flemish and German artists of the Northern renaissance.

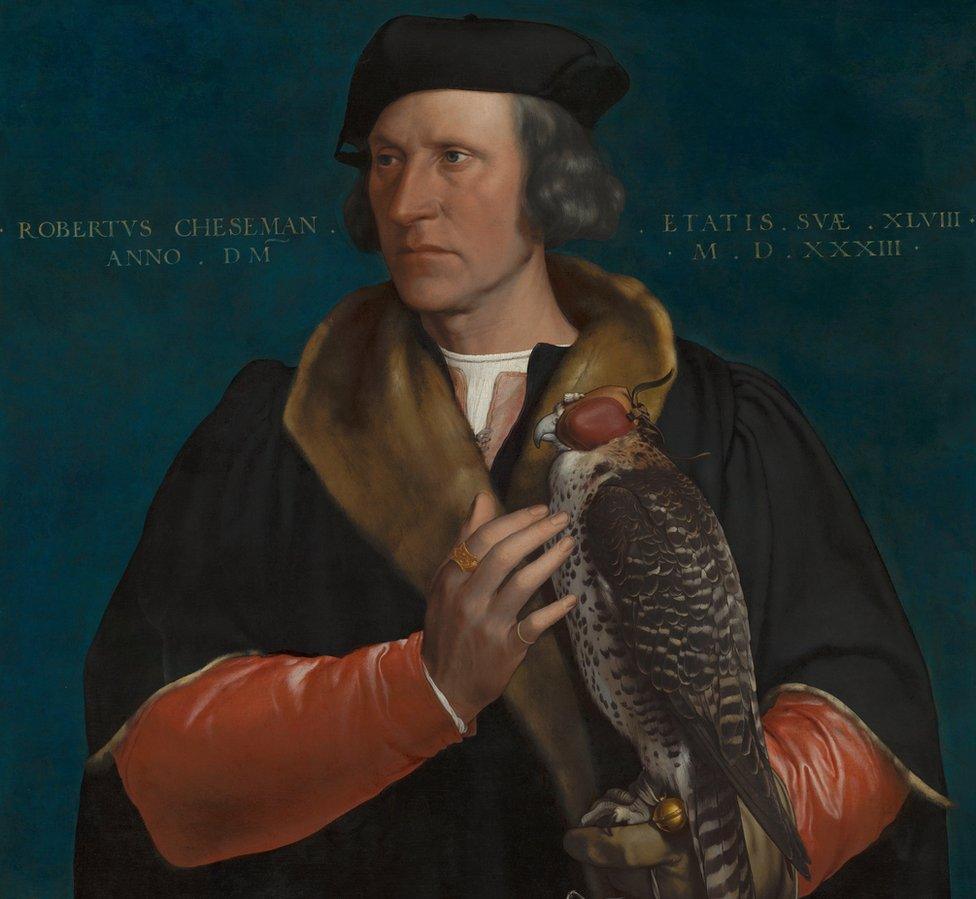

In a gallery decorated in a deep, dark blue, we are presented with a wonder wall of Hans Holbein portraits, the star of which is a tough looking Robert Cheesman (1533), the Royal Falconer. Opposite him is an exquisite painting by Albrecht Dürer of the Burkhard of Speyer (1506), and a small but perfectly formed Pieter Bruegel the Elder oil on panel, Three Soldiers (1568).

Robert Cheseman by Hans Holbein the Younger

From here we move onto the Italian Renaissance and works by Bassano, Correggio, and most prominently, Titian.

Honestly, I would forgive Cromwell his short-sighted philistinism if only he hadn't sold the three huge paintings by the great Venetian master that hang side-by-side in this show. The Allocution of Alfonso d'Avalos to his Troops (1540-41) is now owned by the Prado, while The Supper at Emmaus (c. 1534) and heart-achingly beautiful Conjugal Allegory (1530-35) are both the property of the Louvre.

The Allocution of Alfonso d’Avalos to His Troops by Titian

You can't helping thinking 'what if…' as you walk through room after room of incredible paintings.

What if the King hadn't lost his head? What if he and Henrietta had continued to collect at the same rate for another twenty years? What if his son, Charles II, had carried on in the same manner?

The answer is, the finest collection of outstanding renaissance art ever amassed in a single country would be in Britain.

Sadly, that is not the case. But this fabulous show does at least give us a tantalising glimpse of what could have been.

- Published9 December 2017

- Published25 January 2018