Annie Swynnerton: The woman who forced open the male art world

- Published

Annie Swynnerton's portrait of suffragist leader Dame Millicent Fawcett

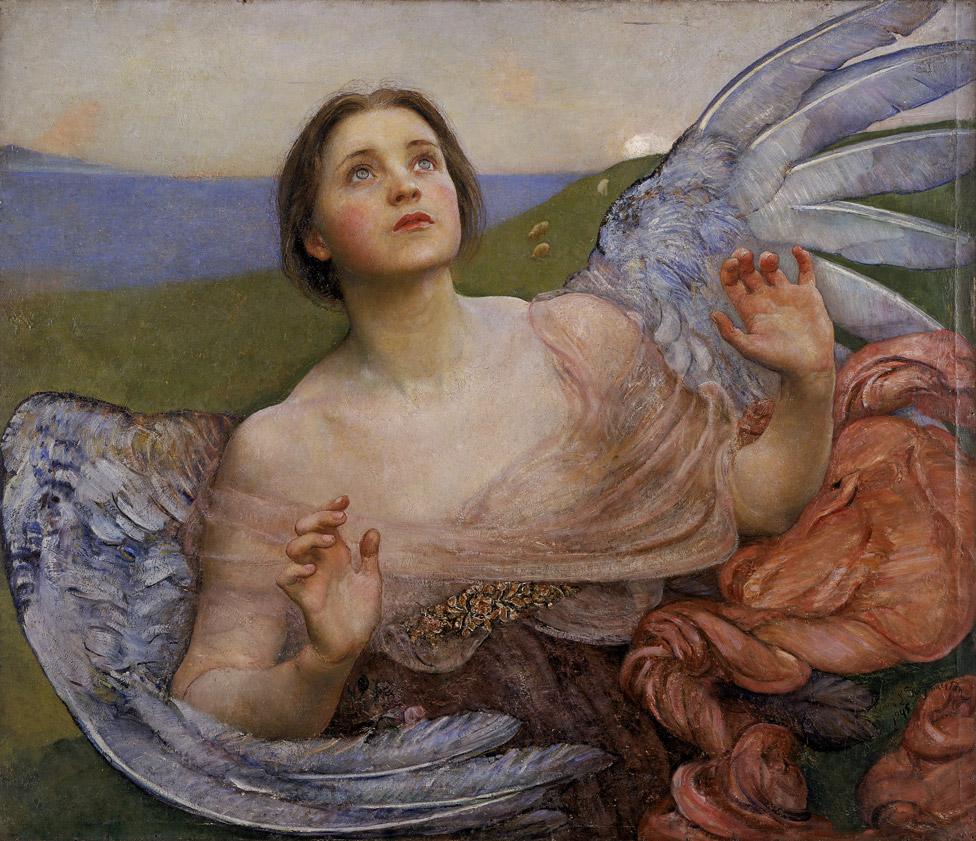

Photoshop had not been invented, but most female bodies in Victorian art were effectively airbrushed - usually painted by men as idealised objects of beauty.

Annie Swynnerton saw things differently, and blazed a trail for female artists.

When she was elected to the most exclusive society in British art, the Royal Academy (RA), it was a male-only club.

It was 1922 and she was the first woman to join since the Academy's foundation 154 years earlier.

In fact, it had taken the RA so long to let Swynnerton in that she was 77 by the time she was admitted - and most men relinquished their positions at the age of 75.

The Sense of Sight by Annie Swynnerton (1895)

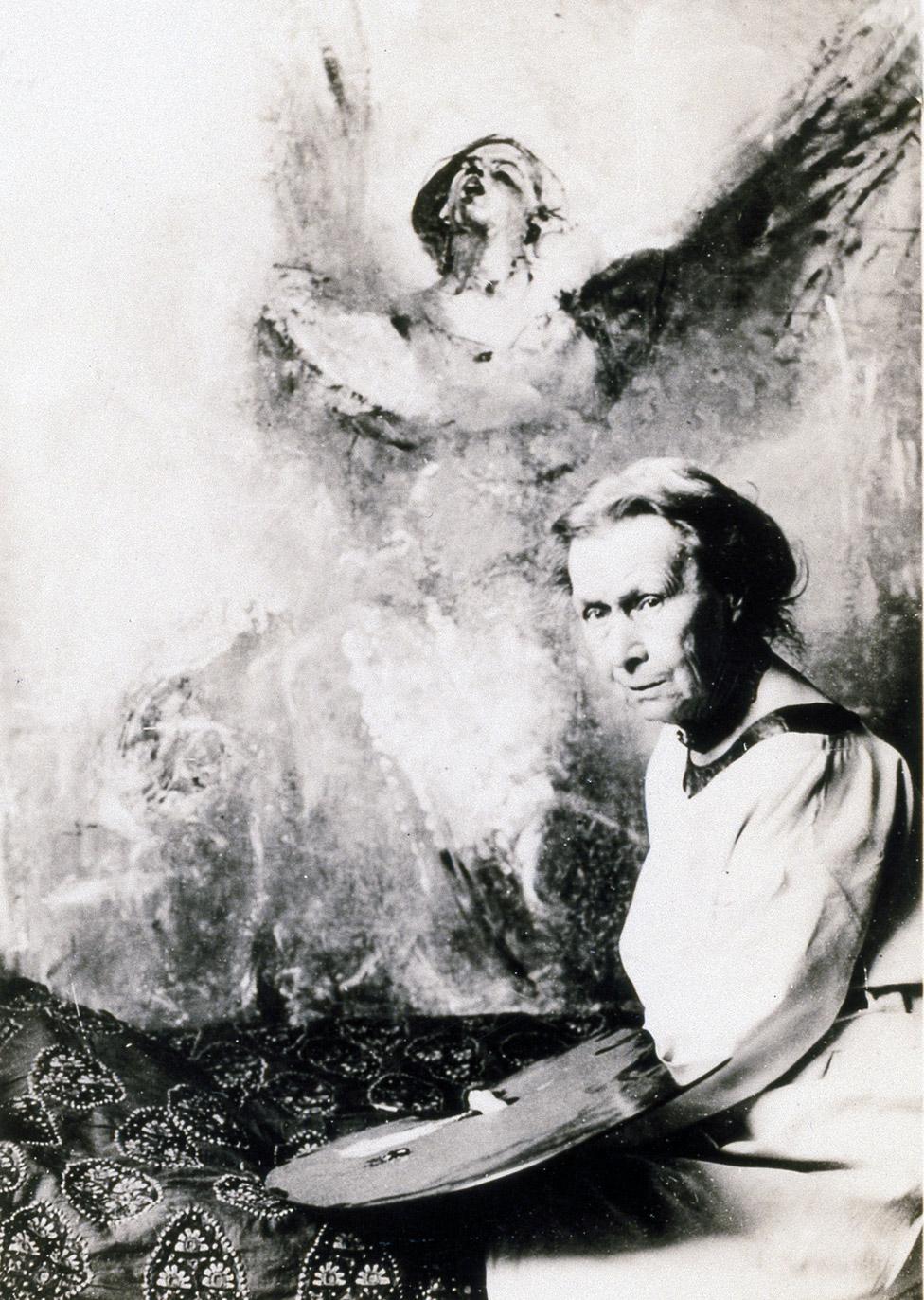

The Manchester-born artist was only admitted after lobbying by more famous male admirers of her work.

Even then she was not to allowed to be a full member: she was only made an associate member.

By that time, Swynnerton had become used to encountering obstacles in the course of her art, stating that she had "fought and suffered" for recognition.

"I have had to struggle so hard," she said in 1933, shortly before her death.

"You see, when I was young, women could not paint - or so it was said.

"The world believed that and did not want the work of women, however sincere, however good," she added.

Annie Swynnerton, pictured in 1931

Swynnerton's talent, and her role in achieving some recognition for female artists, is being celebrated after decades of neglect.

Manchester Art Gallery is staging the first full exhibition of her work since 1923, the year after she joined the RA.

Rebecca Milner, a curator at the gallery, says there was "a lot of prejudice" in the late Victorian period, when Swynnerton was trying to forge her career.

"There was suspicion that female artists weren't capable of great intellectual thought and they wouldn't be able to express big ideas in their work or paint in the same way as men," Milner says.

Dame Laura Knight, who in 1936 became the first woman to become a full member of the RA, once said: "We women who have the good fortune to be born later than Mrs Swynnerton profit by her accomplishments."

"Any woman reaching the heights in the fine arts had been almost unknown until Mrs Swynnerton came and broke down the barriers of prejudice."

Swynnerton faced prejudice not just for her gender but also for her realistic, unromanticised depiction of female bodies, which was dismissed by those who preferred unblemished classical fantasy.

She could not even study life drawing in Britain - female students at Manchester School of Art were only allowed access to draped figures - so she travelled to Rome and Paris to do so.

Illusions by Annie Swynnerton (c 1902)

In 1879, infuriated by the refusal of Manchester Academy of Fine Arts to admit women, Swynnerton and her friend Isabel Dacre established their own association.

The Manchester Society of Women Painters held exhibitions and art classes, including life drawing, for five years, until the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts relented and accepted women on an equal footing to men.

Rebecca Milner says: "There is an almost 10-year-struggle within Manchester when these women are trying to break down those barriers for training and they eventually achieve their goal."

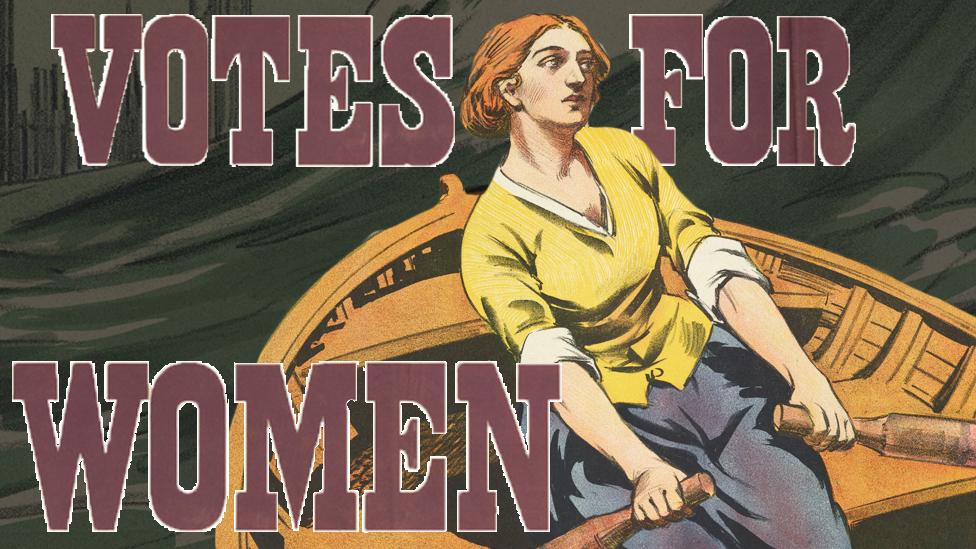

Swynnerton's art was intertwined with activism and politics.

She signed the Declaration in Favour of Women's Suffrage in 1889 and led the Artists' Suffrage League section of the Women's Coronation Procession in 1911.

Her clear-eyed, independent-minded depictions of her subjects appealed to fellow artists and members of the suffrage movement.

Some bought her paintings, while others - like suffragist leader Dame Millicent Fawcett - sat for portraits.

"These networks of women were supporting each other to bolster their attempts to be professionals in their chosen spheres," Milner says.

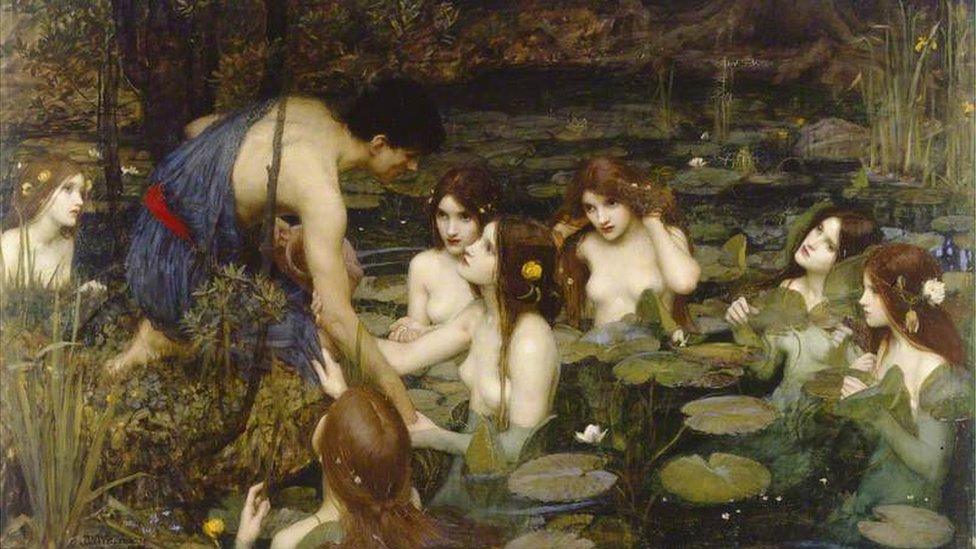

Cupid & Psyche by Annie Swynnerton (1890)

Swynnerton's honest depictions of the female body divided opinion.

Critic Frederic George Stephens found the female figure in 1890's Cupid and Psyche to have "coarse and blubbered" features.

"Her flesh is without the sweetness, evenness or purity of youth," he said.

But the Art Journal's Claude Phillips said Psyche's flesh "has a certain quivering reality not to be found in many renderings of the nude by contemporary British artists".

Despite the differing opinions, Swynnerton's reputation grew.

John Singer Sargent bought 1907's Oreads, which led him to declare the artist "one of the greatest modern painters".

Singer Sargent was among her supporters when she was first nominated for the Royal Academy in 1914.

But the suffragette attacks on the gallery's paintings that year were not helpful to her cause.

Swynnerton's next nomination came in 1920, and she was made an associate member at the third attempt two years later.

Portrait of Annie Swynnerton by Gwenny Griffiths (1928)

Since Swynnerton's breakthrough, things have moved forward slowly.

Today, 28% of Royal Academicians are women, though 44% of those elected in the last 10 years have been women.

Last year, the Guardian reported, external that work by men far outnumbers those by women in some public collections.

For instance, 20% of the art at the Whitworth gallery in Manchester is by women, with a figure of 35% at Tate Modern.

It has taken 95 years for a new Swynnerton exhibition to be staged.

That is mainly because public galleries only started acquiring her work after she was elected to the RA.

Many other Victorian women are still overlooked.

"A lot of female artists from that generation have suffered in the same way," Milner says.

"We're quite lucky that a reasonable amount of Swynnerton's work survived in public collections," she adds.

Annie Swynnerton: Painting Light and Hope is at Manchester Art Gallery until 6 January 2019.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published2 February 2018

- Published1 February 2018

- Published11 February 2017

- Published21 September 2016

- Published21 March 2015