Obituary: Juliette Gréco dies aged 93

- Published

In 2009, the teenage actress Carey Mulligan lay in a suburban bedroom; listening to music and fantasising of escape.

The film was An Education. Her character yearned for freedom and a life of high culture and romantic love.

The voice drifting through the room belonged to the artist who lived the life she dreamed of: inspiring philosophers, drinking with hell-raisers and falling deeply, and repeatedly, in love with her fellow stars.

That voice belonged to Juliette Gréco, the sexy chanteuse who personified the spirit and style of post-war Paris and who later inherited Édith Piaf's exquisite mantle as grande-dame of French song.

Captured by the Gestapo

Gréco was born on 7 February, 1927 in Montpellier on the French Mediterranean coast.

Her father, a police commissioner from Corsica, walked out when Juliette was still small. She, and her sister Charlotte, were raised mainly by their grandparents, and the nuns at the local convent, until their mother moved them to Paris.

It was wartime and Paris was an occupied city. Juliette's mother risked everything working with the Resistance. In 1943, disaster struck and the Gestapo arrested them all. "A French Gestapo officer humiliated me," she recalled. "I became so upset that I punched him on the nose. Well, that cost me!"

As a teenager, Juliette Gréco was captured by the Gestapo and thrown into prison

Her mother and sister were hauled off to the Ravensbrück concentration camp in northern Germany. It was a women-only prison opened on the personal orders of Heinrich Himmler.

Many were gassed, thousands more perished of disease, starvation, overwork and despair. In all, 50,000 women died within its walls before the war was over.

Juliette was spared the camps. Just 15 years old, she was thrown into the notorious women's prison in Fresnes, just south of Paris. It was a foul place where the Gestapo held, tortured and often murdered members of the Resistance.

Released a few months later, all she had were the blue cotton dress and sandals she'd been wearing when she was rounded up. It was the coldest winter on record and she had no home to return to. So Gréco walked the eight miles back into town.

Miraculously, both mother and daughter made it through Ravensbrück. After the liberation, Juliette went every day to the Lutétia hotel, where survivors were arriving. One day, among a crowd of skeletal, liberated prisoners, she spotted them. "We held each other tight, in silence. There were no words for what I felt at that instant."

Existentialist muse

The war over, Juliette moved to Saint-Germain-des-Prés, on the left bank of the Seine, making ends meet singing in cafes. "I had no food, so I bought a pipe and some very strong tobacco, and I smoked it in my room so I could forget my hunger", she said.

Orson Welles and Juliette Gréco in Crack In The Mirror. The two were friends from the post-war Parisian social scene

Dirt poor, she was reliant on male friends to lend her things to wear. Everything was too big but it kept out the cold. The baggy clothes, the long black hair, her stunning looks and dark makeup meant you couldn't miss her. She was "the black muse of Saint-Germain-des-Prés", captivating the Parisian post-war beau-monde.

In 1946, they would gather at the famous cellar club, Le Tabou; Juliette Gréco at the microphone, Picasso, Orson Welles and Marlene Dietrich at the bar. Marlon Brando would give her a lift home on his bike.

The existentialists loved her for the way she looked. Juliette was fascinated by their unconventional style and mindset. "Black provides space for the imaginary," she said. They all believed in living for the now.

Photographers Robert Doisneau and Henri Cartier-Bresson captured her beauty with their cameras. Jean Cocteau asked her to star in his film, Orpheus.

But she was also loved for her voice, the perfect interpreter of melancholy songs capturing a post-war generation's hunger for life as freedom returned to the city.

Philosophers and writers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus both wrote lyrics for her. "Her voice carries millions of poems that haven't been written yet," Sartre insisted. "It is like a warm light that revives the embers burning inside of us all. In her mouth, my words become precious stones."

Miles Davis

Existentialism gave post-war Paris its intellectual identity. But its soundtrack was American jazz.

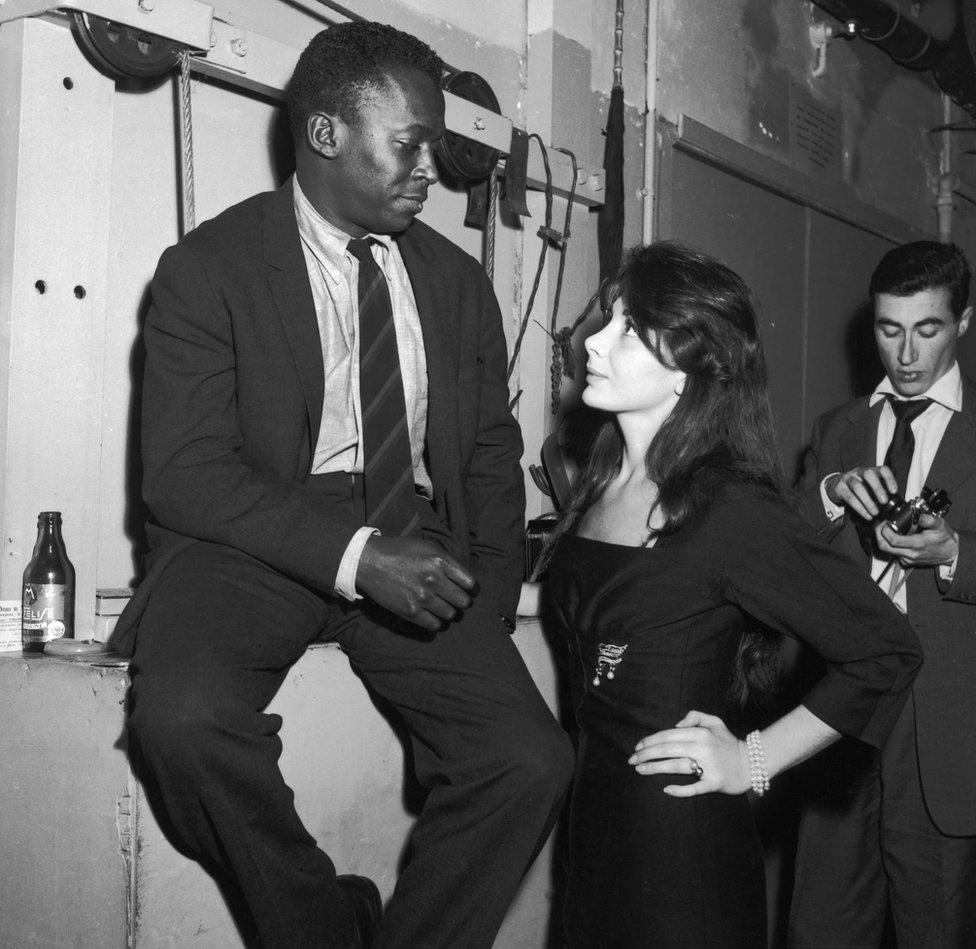

Miles Davis and Juliette Gréco in the 1950s. They had a passionate love affair but never married. "You'd be seen as a negro's whore in America", he told her

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Django Reinhardt were all huge stars. Of course, she knew them all. One night, unable to afford a ticket, Gréco snuck back stage at the Salle Pleyel on the Rue Faubourg Saint Honoré, to watch the legendary jazz trumpeter, Miles Davis.

It would be the beginning of a passionate love affair that would last until the end of his life. He was already married, with a child fathered at the age of 17. He spoke no French, she had no English. None of that mattered in bohemian Paris.

Gréco was transfixed by his looks and his talent. "In profile, he was a real Giacometti", she said. "He had a face of great beauty. You didn't have to be a scholar or a specialist in jazz to be struck by him. There was such an unusual harmony between the man, the instrument and the sound - it was pretty shattering."

"Why don't you marry her?" asked Jean-Paul Sartre. "Because I love her too much to make her unhappy," came Miles Davis' reply. The problem was his colour. "You'd be seen as a negro's whore in America", he said. "It would destroy your career."

Juliette Gréco on holidays in the 1950s

Years later, there was a terrible incident in New York, which Davis said proved him right. Gréco had a nice suite at the Waldorf Hotel and invited Miles to dinner. "The face of the maitre d'hôtel when he came in was indescribable", she recalled.

"After two hours, the food was more or less thrown in our faces. The meal was long and painful, and he left." She took the waiter's hand, made as if she were about to kiss it, and spat in his palm.

At four o'clock in the morning, Davis called her. He was in tears. "I couldn't come by myself," he said. "I don't ever want to see you again here, in a country where this kind of relationship is impossible." She realised they had made a terrible mistake. The humiliation bit deep.

"In America, his colour was made blatantly obvious to me, whereas in Paris I didn't even notice that he was black", she later wrote.

He was not her only lover. There were dozens of heartbroken men, and some women, left reeling in her wake. Some even committed suicide after she left them.

She was unapologetic that she spread her affections so widely. "What do I care what other people think?," she'd say to anyone who asked.

It was said she loved the philosopher, Albert Camus, and the racing driver, Jean-Pierre Wimille, until he was killed in the Buenos Aires Grand Prix.

Juliette Gréco with Darryl F Zalnuck (left). The movie mogul was one of many to fall for her

There was Hollywood movie mogul, Darryl F Zanuck. He gave her a starring role in John Huston's Roots of Heaven alongside Errol Flynn. Another tycoon, David O Selznick, sent her a private plane so she could dine with him in London and offered her a fortune to sign a 7 year contract.

"I declined politely, trying not to laugh," she said. "Hollywood was definitely not for me."

There were three marriages; to actors Philippe Lemaire, with whom she had a daughter, and Michel Piccoli. And then, for twenty years, to the pianist Gérard Jouannest until his death in 2018.

Music and politics

Gréco was less a composer than a great interpreter of other people's songs, notably Jacques Brel and George Brassens.

The French newspaper, Libération, said she spat and caressed "the words like a Fauvist painter crushes colours onto his canvas with his knife".

Si Tu T'imagines, Parlez-moi d`Amour and Je Suis Comme Je Suis were the big hits of the early years. Later, there were collaborations with Serge Gainsbourg, never one to miss working with a beautiful woman.

She became a sought-after performer far beyond the cafes of Saint-Germain, constantly in demand world-wide, including Germany, the US and Japan.

Scarred by her experience with the Gestapo, she hesitated to star in the country responsible for Ravensbrück. She finally agreed in 1959, singing with tears in her eyes remembering her mother's treatment.

Juliette Gréco on stage at the age of 87. She was very proud that young people made up most of the audience

But she kept returning to Hamburg and Berlin, mixing her own material with songs by her friend, Marlene Dietrich. In 2005, she even released an album in German, Abendlied (Evening Song).

Politically, she was firmly on the left. She campaigned against the wars in both Algeria and Vietnam. And then, there was her command performance for Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator in 1981.

He thought it was a coup persuading the great star to perform in Santiago. She walked on to rapturous applause and gave him a show entirely consisting of songs he had banned. "I went off to dead silence", she recalled. "It was the greatest triumph of my career."

Musically, she forever experimented. In 2009, she released Je Me Souviens de Tout, an album mixing the traditional with cutting-edge French song, including rapper-cum-slam-poet, Abd Al Malik.

Gréco refused to remain forever the existentialist it-girl of the 1940s, preferring to look forwards rather than back.

But a few years later, at the age of 87, it was time to say goodbye. It would not be long before a stroke would cut her down. She launched a worldwide farewell tour, Merci. Thousands packed the great Olympia Hall in Paris, to see the legend for the last time.

The high priestess' of existentialism played out in style, treating the crowds to classics such as Déshabillez-moi, Sous Le Ciel de Paris and Jack Brel's great anthem, Amsterdam.

The grande-dame of French song, she may have been. But on that emotional night, she performed to an audience made up almost entirely of young people.

After an astonishing life and career that had lasted more than 70 years, Juliette Gréco was immensely proud of that.