What could Brexit mean for the UK's creative talent?

- Published

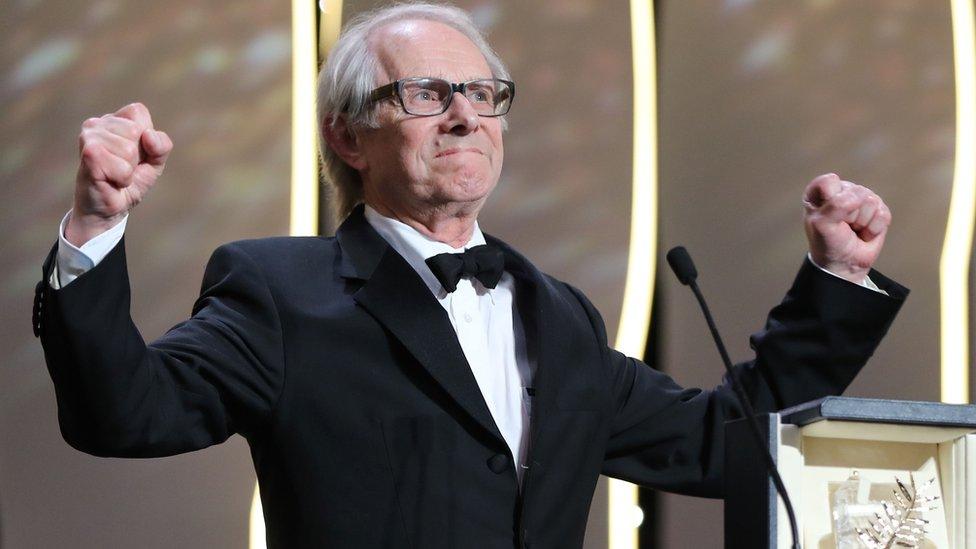

Scottish pop group Chvrches will play at Spain's Primavera Sound festival this weekend

From Adele to James Bond, from David Hockney to Harry Potter, the UK's creative talent is admired around the globe.

And the creative industries are one of the UK's fastest growing sectors, growing at twice the rate of the overall economy, external.

Those in the creative industries are far more anti-Brexit than the rest of the country - a poll by the Creative Industries Federation (CIF) found 96% of its members voted Remain in the 2016 referendum.

Personal politics aside, there are practical reasons why people in the arts are worried that Brexit will be bad news - including their concerns about free movement of talent, funding and Britain's reputation around the world.

But others are seeing silver linings.

Here are some of the ways Brexit could affect the UK's creative industries and talent.

Performers face tour burden

Arctic Monkeys, Idles (pictured), Chvrches and Jorja Smith are just some of the 40 UK acts travelling to play at this weekend's Primavera Sound festival in Barcelona.

As well as worries about the end of free movement having an impact on people wanting to live and work in another country, there are also concerns that it will make it more difficult for musicians and other performers to go on tour.

They may need visas for themselves and their crew, and could need carnets - documents allowing the temporary movement of goods - for their instruments and equipment.

There might also be complex tax procedures and lengthy customs checks. All that could be expensive and time-consuming to organise.

Big-name acts will probably feel the effects less, but there are fears that it will be prohibitive for up-and-coming artists and larger ensembles.

The same applies to European performers wanting to travel to the UK.

Former Labour MP Michael Dugher, chief executive of trade body UK Music, has called on the government to bring in a "touring passport", external to get around any extra red tape and cost.

Han Solo is still free to travel

Britain's film and TV industries have been booming of late, thanks largely to Hollywood studios choosing the UK to film blockbusters like Solo: A Star Wars Story, Mission: Impossible - Fallout and Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom.

Foreign studios spent £1.7bn in the UK in 2017 - almost double the amount spent four years previously.

Most of that money came from America, encouraged by the fall in the value of the pound after the UK voted to leave the EU, which makes it more attractive for US studios to film in the UK. If, as Brexiteers hope, a wide-ranging free trade deal is struck with the US, the trend could well continue.

Some film-makers are worried about being able to recruit crew members from Europe to work in the UK, though, and have voiced concerns about European co-productions, funding and distribution schemes.

However, Lord Puttnam, who produced Chariots of Fire and is president of the Film Distributors' Association, has said more investment in home-grown films "with a distinctive British voice could help to deliver a form of national re-branding".

The Gruffalo and free movement

Axel Scheffler says The Gruffalo would not have existed if the UK wasn't in the EU

If the UK had never been in the EU, children's favourite The Gruffalo - one of every child's favourite books - wouldn't have existed, its German-born illustrator Axel Scheffler recently said.

He brought the character - and many others - to life, working with writer Julia Donaldson in what must be one of the most successful UK-EU creative partnerships.

He moved to the UK 36 years ago and said that without free movement, he wouldn't have been able to make his home in Britain and team up with Donaldson.

Scheffler is one of thousands of Europeans in creative jobs in the UK - the CIF estimated there were at least 130,000 EU nationals working in the sector in 2016.

Some areas rely on European talent more than others. An estimated 30% of people working in visual effects for film and TV were from the EU, with the figure at 20-30% for video games and 25% for architecture.

One of the biggest concerns about Brexit is that some of those people will want to - or be forced to - go home. It's also feared that others will be put off coming to the UK or be unable to do so, meaning artistic collaborations may not happen and some companies may struggle to attract the necessary talent.

In December, a joint document, external issued by the UK government and the EU said both EU citizens and UK nationals will be able "to live, work or study as they currently do under the same conditions as under Union law" after Brexit.

The late Martin Roth, the German museum director who took London's V&A to new heights, said upon his departure in September 2016 that he might not have taken the post if it had come up after the EU referendum.

"I'd probably still be offered a job, but the question is rather, would that job still be as attractive in such a context?" he said.

Will TV broadcasters relocate?

UK media watchdog Ofcom currently regulates around 1,200 TV services. But almost a third of those do not broadcast to UK viewers.

They are based in the UK - but the current "country of origin" rule says media outlets can serve the whole of the EU as long as they abide by the rules of their host country.

Some of these companies are considering relocating if they can no longer reach the whole of the EU from the UK, while others have put plans for new investment in the UK on hold, Ofcom said last year, external.

The Guardian has reported, external that Discovery is planning to move its European playout hub from London.

No more EU funding

English arts organisations received £345m from the EU between 2007 and 2016, according to Arts Council England (ACE).

However, an ACE report said only 14% of its organisations have direct EU funding, with 30% of the organisations saying they have benefitted indirectly from EU funding.

Those getting funding include the Hall for Cornwall in Truro, which has £2.1m European Regional Development Funding to help pay for a new creative industries workspace unit.

In August 2016, the government said it would guarantee to support some EU-funded projects after the UK leaves the EU.

And no more European Capitals of Culture

Amid all the speculation about what might happen after Brexit, there is one concrete consequence we do know about.

In November, the European Commission cancelled the UK's turn to host the European Capital of Culture in 2023 - because the UK will have left the EU by then.

Dundee, Nottingham, Leeds, Milton Keynes and Belfast/Derry had their eyes on the boost to their economies and images that the title would have brought.

When Liverpool was the UK's last Capital of Culture in 2008, it saw an extra 9.7 million visits and a £750m injection into the local economy.

Open for business?

When ACE published a survey of its members' views on Brexit, external in February, one of the key concerns was that the vote would harm the UK's global standing.

"There are significant concerns about the potential negative impact of Brexit on the UK's international reputation for arts and culture," its report said.

One of the organisations quoted, Newcastle-based Isis Arts, works with many European partners.

"People are not looking to us in quite the same way that they might have done before," they said. "Our position over there in these other countries is slipping away from us. It's such a shame because we were held in very high regard."

The world beyond the EU

But the CIF points out that there are opportunities for British firms and talent beyond the EU.

It talks about catering for "the expanding middle class in nations from Chile to China", especially through new digital technologies.

Architects' body RIBA says the UK can fill a skills shortage in the US, while institutions like the V&A and the British Museum have been making inroads in Asia and the Middle East.

The CIF quotes Diane Banks of Diane Banks Associates Literary & Talent Agency as saying: "Investors are much more interested in our access to North American and Asian markets than the EU as these markets offer the highest growth potential, particularly when dealing with an English-language product.

"Leaving the EU will also present exciting opportunities to innovate and be more competitive."

Michael Lightfoot, who started the group Artists For Brexit, says: "We are very keen on trying to promote the notion of global Britain. You're shifting your emphasis to being interested in and having equitable exchange with the world, which has got to be brilliant for the arts."

Other factors

There are other big issues for people across the British creative sector - who say copyright protection should be maintained, data should still be able to flow freely between the UK and EU, and tariffs shouldn't raise costs for businesses and prices for consumers on exporting things like books, video games and art.

Artists get to grips with dramatic times

Aside from the economic implications, we're seeing a new breed of artists and writers who have been stirred to give their creative responses to Brexit and the wider political climate.

The Young Vic's incoming artistic director Kwame Kwei-Armah (pictured) recently told The Stage, external: "We can't rest on our laurels, but we're in great shape as a country [for political writing] because Brexit, wherever you sit on it, has awoken a generation [of playwrights]."

At the very least, Brexit has given Benedict Cumberbatch another job.

Will the UK exit Eurovision?

Thankfully - or not, depending on your view - the Eurovision Song Contest has nothing to do with the European Union.

Israel, Azerbaijan and Australia are among the non-EU countries who take part in the annual song extravaganza. So the UK can continue to compete.

Unfortunately, Eurovision is the one part of the creative sector where the UK is a consistent failure.

- Published17 May 2018

- Published11 April 2019

- Published23 November 2017

- Published19 October 2017

- Published5 July 2017

- Published5 April 2017