Will Gompertz reviews Sam Mendes' The Lehman Trilogy at the National Theatre ★★★★☆

- Published

The Lehman Trilogy at the National Theatre is both specific and universal.

It is, as they like to say in the arts nowadays, "relatable". Meaning, the play resonates beyond a story of a banking dynasty, which could have limited appeal, to explore themes that a broader audience might recognise and enjoy.

You could, for instance, take the two big domestic news events of this week - the end of England's World Cup dream, and Donald Trump's presidential visit - and find parallels within the play.

It is, after all, a story of a band of overachieving brothers, who succeed against the odds, having made the world believe in them, only to ultimately fail; while also being a tale of big business, the American Dream, international trade, powerful egos, and acts of brinkmanship.

So there you go, it is relatable. And good.

Ben Miles (Emanuel), Adam Godley (Mayer) and Simon Russell Beale (Henry) on the set designed by Es Devlin

Which is hardly surprising. The creative team behind the show reads like a contemporary theatre supergroup. It is directed by Sam Mendes, designed by Es Devlin, and performed by Simon Russell Beale, Ben Miles, and Adam Godley (each actor takes on multiple roles).

Broadly speaking it tells the Lehman Brothers story (adapted and translated by Ben Power from Stefano Massini's original 2013 stage play) in chronological order, played out in three acts.

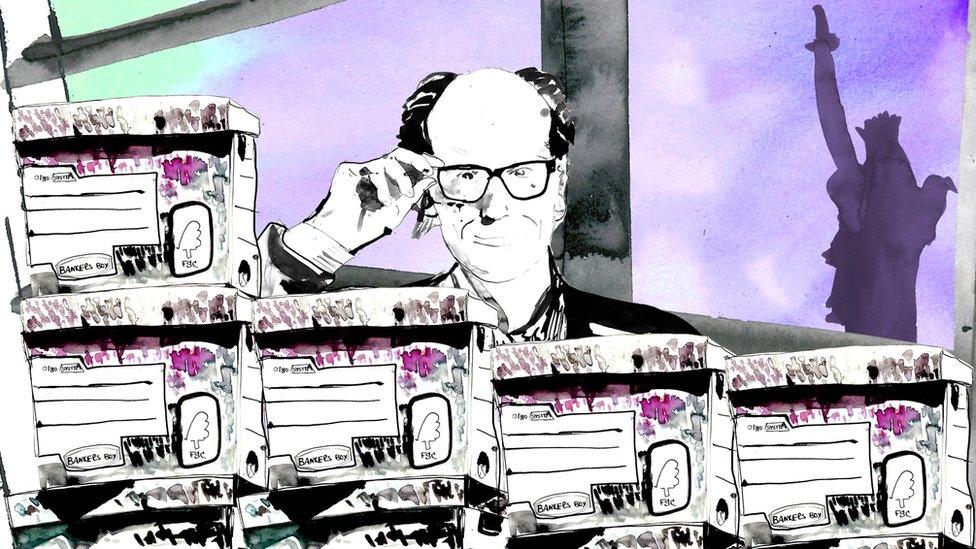

The set remains the same throughout. It consists of a revolving stage, divided into quarters by glass panels between which is a sparse array of office furniture and cardboard archive boxes. Behind it is a huge panoramic screen onto which video scenery is projected. The entire production is presented in a grisaille palette.

The three actors are terrific.

The three actors "are terrific" and take on multiple roles

They seamlessly change characters through subtle shifts in posture, or a change of voice, or by putting on a pair of spectacles or black hat. They hop between first and third person with obvious glee, occasionally tapping at, but not breaking, the fourth wall. To change scene they walk into another section as the stage rotates, a visual segue that echoes Es Devlin's award-winning set design for Chimerica in 2013.

This is a play that is more tell than show. The actors narrate the Lehman Brothers story to the accompaniment of a single upright piano that helps drive the production forward like those ever-present music beds beloved by podcast producers.

The story itself is a familiar rags-to-riches tale of immigrants coming to America and making it big. It starts when Hayum Lehman (who changed his name to Henry), a young Jewish man from Rimpar, Bavaria, arrives in New York, having spent many arduous weeks travelling by sea. He is very happy to be there, and proudly announces the auspicious date.

Simon Russell Beale plays the role of the eldest Lehman brother, Hayum (who changed his name to Henry)

It is, he tells us, September 11th 1844, which jars somewhat with the image of the Statue of Liberty behind him. The iconic landmark didn't actually arrive from France until 1886 -- 31 years after poor Henry had died of Yellow Fever aged just 33.

By this time not only had his two brothers, Emanuel and Mayer, joined him in Alabama to take up roles at his small general store, but had also helped their older brother to turn the business into a major cotton trader, and then - after the Civil War - a bank.

The story is the story, but the way it is told touches on the poetic at times.

The use of language and the rhythmical way it is delivered by the actors has the feel of a music score. It seems a ridiculous thing to say of a play about bankers, which one might imagine could well be filled with anger and resentment, but it is often beautiful.

Yet as the romance of the American Dream morphs into a late 20th Century capitalist nightmare the production starts to lose its confidence.

Lehman Brothers staff leaving the firm's London HQ, after it filed for bankruptcy in September 2008

The final 40 years aren't so much rushed through as taken at warp speed. The play starts to feel thin and as short of ideas as those running Lehman's were of morals. It's weird. What should be the most dramatic part of the story lacks any real sense of drama.

Maybe it is too much of a stretch to take an aesthetic that worked so well for telling a romanticised backstory and reapply it to portraying the depraved culture that existed in the feeding frenzy of pre-Crash banking.

Robert "Bobbie" Lehman in circa 1946 (played by Adam Godley), who was the last Lehman to run the company

Or, maybe it is intentional; that the production's soul should go AWOL just at the time the last Lehman left the bank.

Any which way, a slightly disappointing end shouldn't take away from the scale of the achievements reached overall, which, I suppose brings us back to the England football team.