Will Gompertz on Peter Jackson's WWI film They Shall Not Grow Old ★★★★☆

- Published

Times change, things go in and out of fashion.

Back in the 1970s, sensible people were seriously speculating about the Bay City Rollers being the "next Beatles".

Around the same time there was a TV programme that became so popular it was pulling in Strictly-type numbers. It also had stars, sort of. Middle-aged men with names such as Ray and Joe who looked classy in a bow tie but would almost certainly draw the line at sequins.

They didn't sing or dance, they just walked very slowly around a table and bent down a lot. Snooker was their game, Pot Black was the show, and "whispering" Ted Lowe was the broadcasting legend who brought this quiet game alive for millions of armchair fans.

It was Ted who uttered those immortal words, "For those of you watching in black and white, the pink is next to the green."

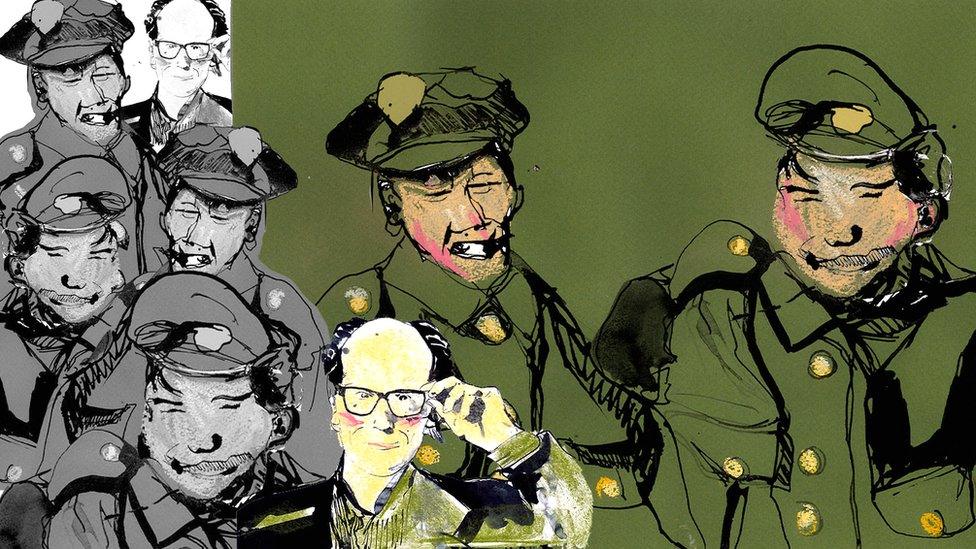

"Whispering" Ted Lowe in the centre (with cue), who uttered those immortal words, "For those of you watching in black & white the pink is next to the green".

You could almost hear the champagne corks popping across the country as TV retailers celebrated a line of commentary that would sell more of their shiny new colour sets than any amount of expensive advertising.

Ted had made it emphatically clear to viewers that they could only really appreciate the nuances of snooker by watching it in colour.

It is a point of view shared by Oscar-winning director Peter Jackson, whose films include Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit and King Kong.

He has applied the same logic to around 600 black-and-white silent films made during World War One, which he has comprehensively remastered into a sound-rich, fully colour 99-minute documentary called They Shall Not Grow Old.

A frame of the original black & white footage of a conflict which Peter Jackson says wasn't "a black & white war"

His contention being that it was not "a black and white war", certainly not for those who were actually fighting it on the Western Front.

Peter Jackson used state-of-the-art digital technology to restore and colourise the footage

It is only perceived as such, he thinks, because that's how it's often presented in film, which has a distancing effect: it makes the Great War feel like a piece of ancient history that belongs to a bygone age rather than a modern conflict in which many people's grandfathers (including Jackson's) fought.

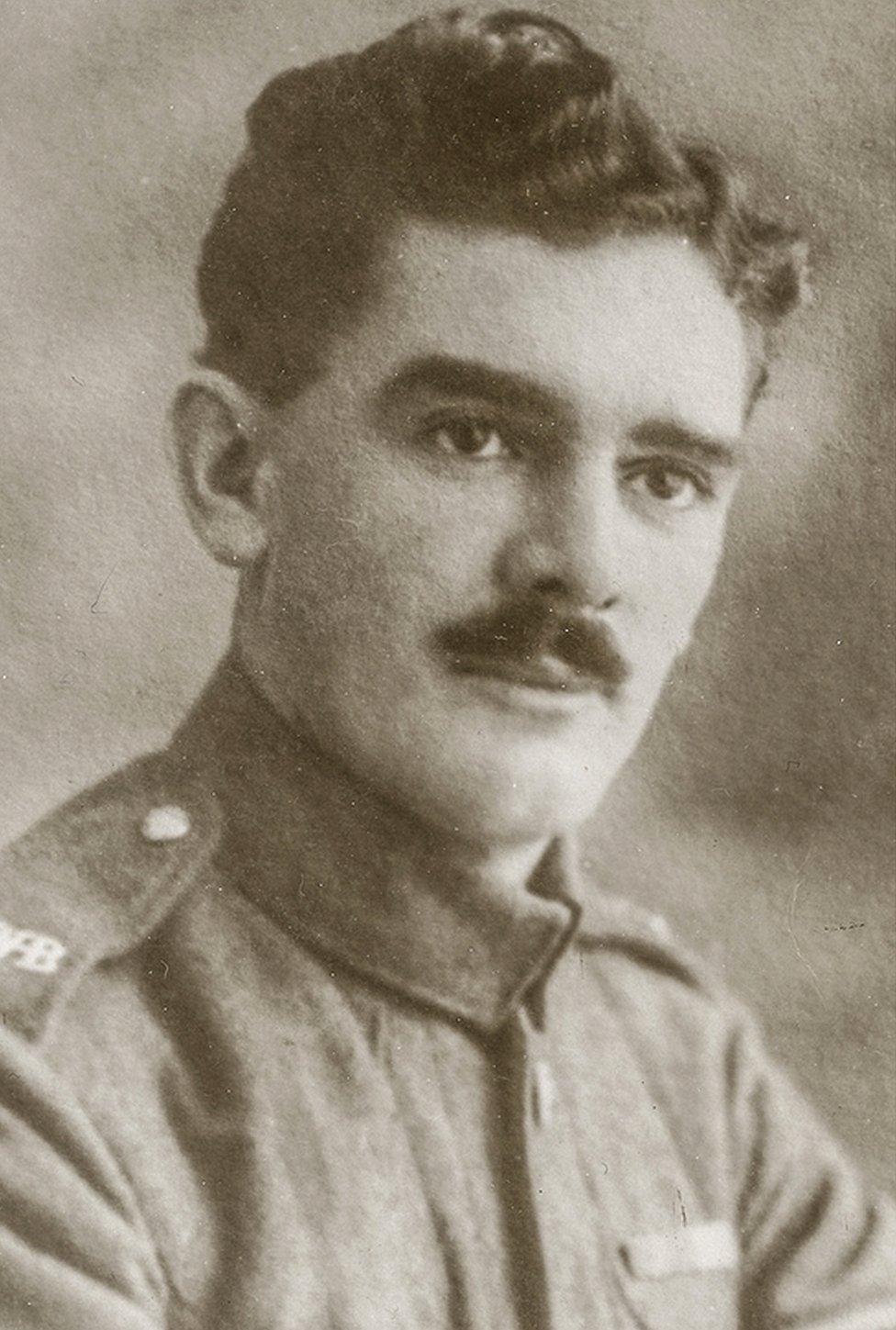

Peter Jackson has a personal interest in WWI, because his grandfather, Sgt William Jackson, fought in the conflict

The reason the films are in black and white was due to technological limitations, Jackson says (access to very rare colour moving-image film was limited), rather than an aesthetic choice taken by the filmmakers.

Hence his willingness to jump into the fairly controversial arena of "colourisation" (the process of transforming back and white footage into colour).

He makes a reasonable point. It is not as if he is producing a colour version of a film that was intentionally made in black and white for artistic reasons. He is attempting to make a documentary that might have been made at the time if colour film had been available.

He applies the same argument to the soundscape that he has added to the old silent films. The result is stunning. His brief to his sound team was short and ambitious: he wanted the viewer to believe that there was a sound recordist accompanying the cameramen out on the battlefields (there wasn't).

The result is extraordinary.

Every action you see has an accompanying sound, from a bottle being juggled to a tin being opened. He hired lip readers to interpret what the soldiers were saying and brought actors in to voice their words. The upshot of which is you watch the film and accept the illusion without hesitation.

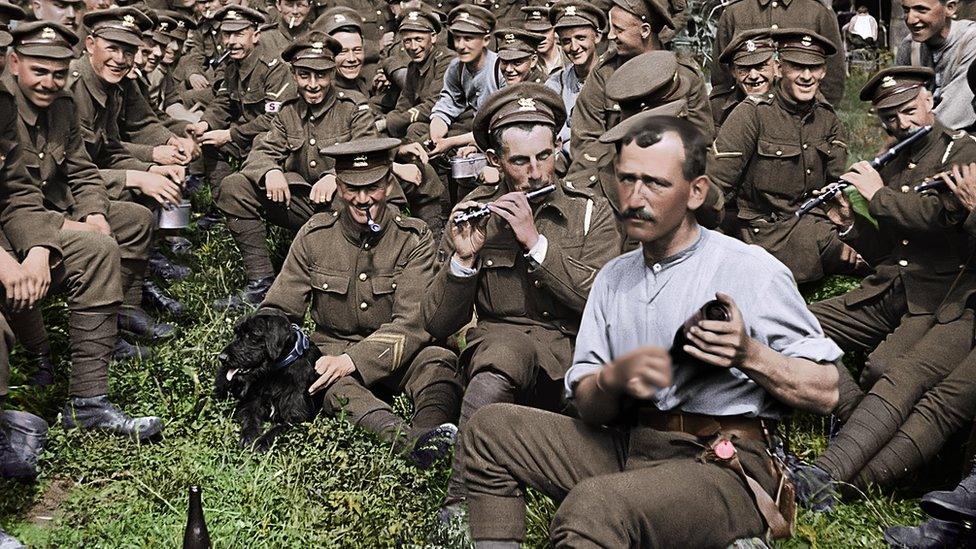

Silent film footage from World War One was painstakingly restored by Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson

The same applies to the colourisation, which has been done with a remarkable attention to detail. Again, you don't question what you're seeing, even though you know perfectly well it is the result of some of the most powerful 21st Century computer graphic kit in the world.

So, five stars to the tech team.

The film itself is also very good and extremely moving. It is solely focused on the Western Front and chronologically follows the events of WWI, starting with enthusiastic 15 and 16 year-old boys fibbing about their age so they could sign up to "have a go at Jerry" in 1914, to its bitter end in 1918.

The story is narrated by multiple voices, all of which belong to those who fought, which Jackson and his team found in BBC and Imperial War Museum audio archives. The first-person accounts and recollections are often surprisingly upbeat, even in the worst of times when wholesale slaughter and rotting flesh became part of everyday life.

Soldiers relaxing in black & white

Colourisation brings to life the footage of soldiers relaxing

The original commissioned by 14-18 NOW (the arts company responsible for creating events and projects to mark the centenary of WWI) was to make a 30-minute documentary using the Imperial War Museum's huge archive of World War One silent films. Jackson quickly realised that it would need to be longer, and it is easy to see why half an hour would be too short.

Ninety-nine minutes though, feels just a tad too long. There are moments at the beginning, middle and end where the film drifts a little: a light edit to bring it down to around eighty-five minutes would be beneficial. That said, it is a brilliantly conceived - and made - film, which I urge you to see.

It will be in cinemas on or around Armistice Day, and also showing on the BBC. There will also be screenings next weekend at the Imperial War Museum in London.

The title of the film - They Shall Not Grow Old - is a line taken from For The Fallen by Laurence Binyon. It is also a reflection of the product, as in there's an almost invisible sleight of hand being used to make it flow and feel more contemporary.

The film ends with a lusty rendition of Mademoiselle from Armentieres (Hinky Dinky Parlez- Vous). I can think of no better way of ending this review than with the original line as Binyon wrote it, and the stanza in which it appears:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.