Why tech is taking a hammering

- Published

The FAANGs have been savaged over the past week

Technology stocks have had a very bad week. For the FAANGs (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google) which have led the charge in growth over the past decade, it was grim.

At their lowest point, all five were down more than 20 per cent from their peaks. This translates to hundreds of billions of dollars in value being wiped from them.

Apple was the first company to cross the $1trn mark this year. It fell to $840bn by close of play on Tuesday, and hasn't recovered since.

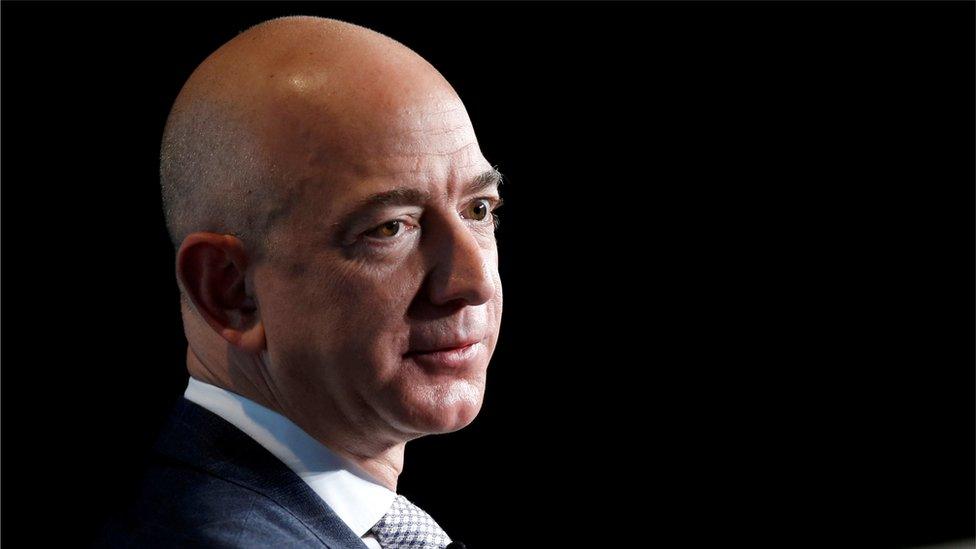

Amazon, which also briefly crossed over the $1trn threshold, dropped to $731bn. That's a quarter of a trillion dollars right there. I know your sympathy for Jeff Bezos may be limited, but these are big numbers. Facebook, meanwhile, is trading at around the value it had early last year - long before the scandals of this year took their toll.

But those scandals may be a distraction from the big pictures. Why are tech stocks taking a hammering, and what does it indicate about the wider macroeconomic picture?

Facebook scandals in 2018 have meant a tough year for Mark Zuckerberg

When considering market fluctuations and, by extension, whether to invest, the key is to look at the fundamentals and over the long-term. Some context here is vital.

Global worries

These companies are still exceptionally rich, staffed by many of the smartest innovators on earth, and good at planning. Moreover, they are registering whopping profits; indeed, record-breaking profits in Amazon's case, and forecast-beating profits for Apple and Facebook.

And given the wider hit to stock markets from weaker global GDP growth, and with a looming potential trade war between America and China, it's inevitable that tech stocks should also be hit.

But a new world is emerging for these companies, in which three fundamental shifts point to a new era that will place limitations on their acceleration. That is not to say they will go into reverse; just that they might slow.

First, monetary policy is tightening around the world. Since the financial crash, we have lived in an extraordinary period of sustained low-interest rates. This has been good for borrowers.

When borrowing is cheap, investors are - relatively speaking - more relaxed about returns. When the cost of borrowing rises, so do investor demands for reliable returns. The shift from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening puts a discipline into the market. Rising interest rates make equities sweat. Tech stocks are feeling the effect.

The second big change, which is well documented, is the threat of national and supranational regulation. A feeling unites legislators from Washington to Brussels, Berlin and Delhi: smarter regulation of these companies is socially necessary and, probably, economically manageable.

Resurgent nationalism in many parts of the world has curtailed the freedom of many global companies, which tech giants almost by definition are. And the example of GDPR in Europe, which aims to shift control of data back to consumers from these companies, is being closely watched. If it is seen to work, it will be widely copied.

Peaking out

The third big change is perhaps less documented, and most alarming for these companies. This is the possibility that they are maxing out on scale.

LinkedIn's Reid Hoffman has been focusing on the idea that the remorseless pursuit of scale is what gives data-based companies their advantage

Reid Hoffman, the co-founder of LinkedIn, has co-authored an important new book called Blitzscaling. This riffs on the idea that it is the remorseless pursuit of scale that gives data-based companies their advantage. The first scaler, rather than the first mover, will emerge victorious in various markets. That, according to Hoffman, is why venture capitalists are happy to tolerate the lack of profits at a company like Uber.

If this argument is right, what if companies like Facebook and Apple have already squeezed most of their advantage from blitzscaling their particular markets?

Apple's growth has long been powered by the iPhone - but its popularity with each new version is slowing, as rivals launch brilliant counter-attacks, and markets become saturated.

In the key markets of US, Canada and Europe, Facebook hasn't grown at all in the past quarter. Think about what that does to the mentality of a company used to super-star growth, on its way to 2.6bn global users.

What if, say, 3bn users is where Facebook will peak? That is why, by the way, the company is trying to make Instagram, which it owns and which is still growing fast, sweat, by putting more ads in that arena.

What if a back-lash against the misuse of data means consumers spend more time in the private arena of WhatsApp, where there are fewer ads, and it's much harder for Facebook (which also owns WhatsApp) to sell me a car in WhatsApp than on the Facebook News Feed?

Never had it so good

Of course it is true that the relentless drip, drip, drip of scandals engulfing some of these companies, especially Facebook, will weigh on investors too.

But go back to the bigger picture. For well over a decade, during which workers of the world dealt with a financial crash and just avoided a depression, these technology companies enjoyed astonishing freedom.

They were able - largely through their own ingenuity - to pursue growth remorselessly in a low-interest rate world, where they endured relatively little regulation. New markets and vistas constantly opened up to them, and their tax affairs were tolerated in a world of globalist sentiment.

Now interest rates are going up, regulation is coming, those markets are nearing saturation, rivals are launching better attacks, nationalism is tempering globalism, and tax affairs are under new scrutiny.

Their valuations may yet rise further, and will almost certainly bounce back from this week. But for the tech sector, a new era brings harder times.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from Radio 4.

- Published18 November 2018

- Published15 November 2018

- Published27 July 2018