Revealed: The winner of the Russell Prize for the best writing of 2018

- Published

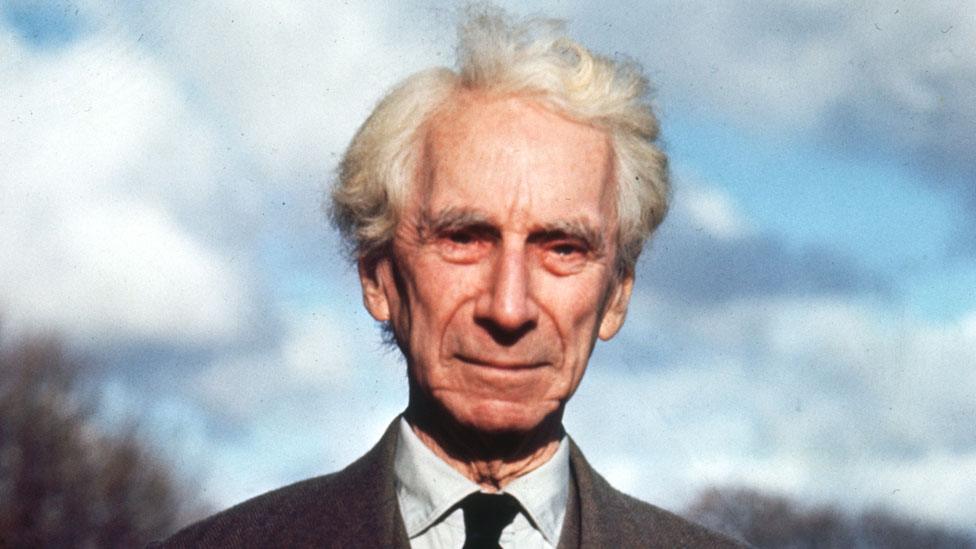

Bertrand Russell's writing combined plain language, pertinent erudition and moral force

And so we come at last to that key annual moment in the life of licence fee payers everywhere: The Russell Prize.

For those unblessed few who had the misfortune to miss last year's inaugural event, this is a prize-giving ceremony in honour of my hero, Bertrand Russell.

It is not Russell's politics or philosophy or life, but rather his writing, that the Russell Prize honours. As I explained last year and am delighted to repeat, the great man's writing achieved a pedigree and level probably unique in the 20th Century, because it contained all three elements of the intellectual trinity that distinguish great writing from the merely good.

First, plain language. Second, pertinent erudition. And third, moral force, especially through an instinctive and visceral revulsion at injustice. Russell's prose contained each of those elements in abundance.

Tough process

I should here, by the glory of copy and paste, remind readers that recipients of these awards have been through a rigorous selection process: they were submitted, by me, to a discerning and impartial selection panel comprised of one member, also me, where I am honoured to hold the title of founder, convenor, president and chair.

So yes, again: anyone who says The Russell Prize is just an excuse to re-up some special writing is completely right... sorry, wrong.

This year's winning candidates are very different in flavour from last year, however. Whereas last year I found myself often sympathetic to the driving arguments of the winning articles, this year I am less often in agreement. In fact, I have some serious beef with arguments that this year's winners have made.

But then again, I have serious beef with arguments that Russell himself made. This is a prize about what makes good writing, and the best writing is often highly disagreeable.

The winner

And the winner of this year's prize is.... drum roll...

Jamelia has penned an open letter to the media for linking her name to crime as clickbait

Jamelia (Jamelia's blog): Named & Shamed... When I'm Not to Blame, external

A stunning, and it turns out winning, late entry.

I found this blog hard to read, don't agree with every point, and am highly conscious that some of the criticism it contained was directed at current and former colleagues.

You should read the details. In essence, it was a long personal complaint about the way in which the media use her name to drive attention to alleged crimes, in this case about her "step-brother", someone whose father Jamelia's mother had a relationship with 36 years ago.

The main reason the article is hard to read is that it is a sustained and informed attack on my trade. I am instinctively defensive about, and in solidarity with, journalists and journalism. But anybody who bothers with the subject can see that we have a huge crisis in our media today, driven not principally by commercial failure but editorial and moral failure.

And Jamelia makes several urgent points: about the permanency of damaging headlines on the web; about the impact of that on children; about the way black women are treated by the media; about the lack of attention given to her frankly admirable charity work, and what that says about our priorities in the news business; about the spurious, stupid way celebrity names are often appended to stories in order to drive audience; and, by extension, about clickbait.

It confirmed some of my prejudices, and challenged many others. How about you?

Runners-up, in no particular order

Luke Johnson has taken a break from his newspaper column while he deals with the crisis that has rocked Patisserie Valerie

Luke Johnson (Sunday Times): How entrepreneurs end up as fresh meat for City slickers (subscription required), external

The entrepreneur Luke Johnson has stopped writing his Sunday Times column in order to fix his ailing Patisserie Valerie business. It reported massive problems about five minutes after he and I met properly for the first time, over breakfast, but I'm hoping that's a coincidence.

He is a straight talker, and his much-missed column brutally demolished many of the vanities that prevail in the world of business. In this, his best column, he called out those city slickers who are selling little more than their own upper-class pretensions.

Lambasting "professionals [who] talk with posh accents", he noted that a quite astonishingly vast sector of our economy is populated by snake-oil merchants selling 'advice' when their defining quality, other than a sharp suit and plummy vowels, is total ignorance whereof they speak. Bravo.

Amia Srinivasan is a contributing editor at the London Review of Books and teaches philosophy at Oxford

Amia Srinivasan (London Review of Books): Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?, external

Modern gender politics is often mis-characterised by those who can't understand what's complicated about boys being boys and girls being girls. It is inseparable from a system of rights, in which membership of a particular group - in this case a whole gender - confers both rights on an individual, and duties on others to respect those rights. Within that respect is the source of dignity which, if violated, can lead to profound anger.

That philosophical approach, rather than #MeToo, is the context in which to read Srinivasan's difficult essay on the nature of gender relations. The LRB, which sits gladly between academia and the broadsheet press, publishes very admirably clear and cogent prose. I found this essay hard, and actually less fun than Srinivasan's brilliant article on the octopus, external, which sadly doesn't qualify because it was published last year, and which should be read alongside David Foster Wallace's immortal Consider the Lobster. , external

Adrian Wooldridge is The Economist's political editor

Adrian Wooldridge (The Economist): The shadow of Enoch Powell, external

When I first pitched and discussed the idea of a documentary on Enoch Powell last year, pegged to the 50th anniversary of his "Rivers of Blood" speech, I mobilised an argument similar to that of Wooldridge, the latest Bagehot columnist for The Economist.

(The Bagehot column is an analysis of British life and politics in the tradition of Walter Bagehot, who was editor of The Economist from 1861 to 1877.)

The argument was twofold: first, that Brexit married two of Powell's greatest interests - Europe and immigration - in the idea of national sovereignty, and therefore some, though not all, Brexiters owed him an intellectual debt.

And second, that together with Roy Jenkins and Margaret Thatcher, Powell was one of three intellectual paradigm shapers of post-war British politics. Of course other politicians had been more successful in elections, but it was these three, more than others, that elucidated the arguments we are still grappling with.

With clarity, erudition and moral force, Wooldridge says it much better than I did.

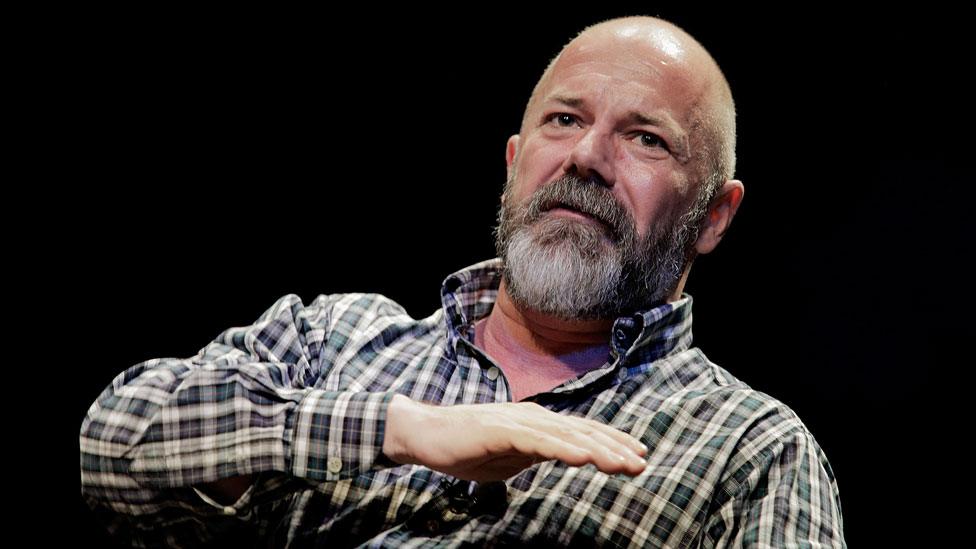

Andrew Sullivan is a British-born American author, editor and blogger

Andrew Sullivan (New York Magazine): Why We Should Say Yes to Drugs, external

To the extent that there is a conversation, or even debate, about drugs in the West today, it mostly concerns the growing calls for a new policy approach, whether through decriminalisation or legalisation.

Andrew Sullivan is one of those writers who, while deeply immersed in the political world, tries to anchor his writing in considerations of ultimate meaning. He unashamedly writes about the big ideas: justice, truth, honour, love.

And his article about personal use of psychedelics used these themes to take the conversation about drugs in a direction not often heard in public. It is a direction that many people, not least many parents, will find unfathomable, or even repulsive.

Sullivan argues that drugs should be seen as an avenue to deep experiences, including connection with heightened consciousness and overwhelming love. Controversial, certainly; but argued with tremendous clarity, erudition and moral force. A worthy runner-up in this year's Russell Prize.

Impartial recommendations

Let me reiterate that I don't endorse or dismiss any of the arguments put forward by this year's prize-winners.

Readers can make up their own minds. I very much hope you will take the time to do just that.

Entries for the 2019 competition open on 1 January.

In the meantime, as I said last year, and will say with pride again: may plain prose and erudition long outlast the injustices our esteemed winners have sought to vanquish.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from Radio 4.

- Published22 December 2017