Obituary: Talk Talk's Mark Hollis

- Published

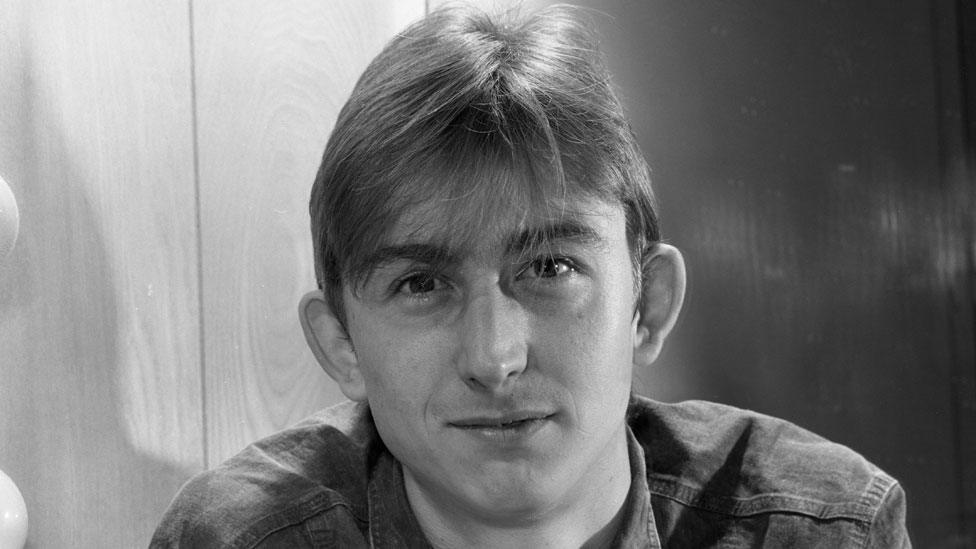

Hollis was the second of three brothers

"Our songs are about tragedy... Human tragedy."

Talk Talk may have been lumped together with synth-pop bands like Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet.

But singer Mark Hollis, who has died after a short illness aged 64, possessed a lyrical depth and musical curiosity that set him apart.

By their fourth album, Spirit of Eden, he'd abandoned pop formulas in favour of ambient textures and jazz structures - setting a blueprint for bands who want to outgrow their origins.

From the outset, Hollis's tastes were eclectic. His first record was the Northern Soul classic Everlasting Love, which he bought at the age of 12, while his first concert was David Bowie.

Speaking to Record Mirror in 1982, he cited his main influences as Burt Bacharach and counterculture icon William Burroughs.

He also said the best live show he'd ever seen was a performance of Shostakovich's Symphony No 10 at London's Royal Festival Hall.

Those facts aside, little is known about Hollis's early life - mainly because of his tendency to tell tall tales in interviews.

Born in Tottenham in north London in 1955, he told one journalist he'd dropped out of school before his A-Levels, while informing another he had studied child psychology at the University of Sussex.

Upon leaving education, he claimed to have worked as a laboratory technician - but music was always his first love.

"I could never wait to get home and start writing songs and lyrics" he told Kim magazine in 1983, external.

"All day long I'd be jotting ideas down on bits of paper and just waiting for the moment when I could put it all down on tape."

Duran comparisons

Hollis formed his first band, The Reaction, in 1977 and recorded a demo for Island Records that included a song called Talk Talk Talk Talk.

The group split after one single, after which Hollis intended to pursue a solo career. After writing a new batch of songs, he recruited Paul Webb, Lee Harris and Simon Brenner to help him flesh out the arrangements in the studio.

"But we liked what we were doing so much that we decided to throw every penny we had into hiring a rehearsal room and practicing to go out and play in the clubs," he said.

Talk Talk were reluctant to be compared to Duran Duran

The quartet soon had a name, Talk Talk, and a record deal with EMI Records, who hoped to mould them into another Duran Duran.

The company even hired that band's producer, Colin Thurston, to work on their first two singles, Mirror Man and Talk Talk.

But the band were keen to shake off the "New Romantic" tag, even dismissing their keyboard player to make it clear they weren't a synth-pop band.

"It gets tiring to listen to the Duran comparisons" Hollis told Noise! magazine at the time. "I can't hear it myself.

"I get depressed about the whole thing [because] kids ought to know about music, not image."

The band deliberately took a year to craft their second album, It's My Life, and even recorded animal noises at London Zoo for the title track.

The video for the song was compiled from rushes of the David Attenborough series Life on Earth.

It's My Life went on to become Talk Talk's biggest hit. A cover by No Doubt reached the US Top 10 in 2003.

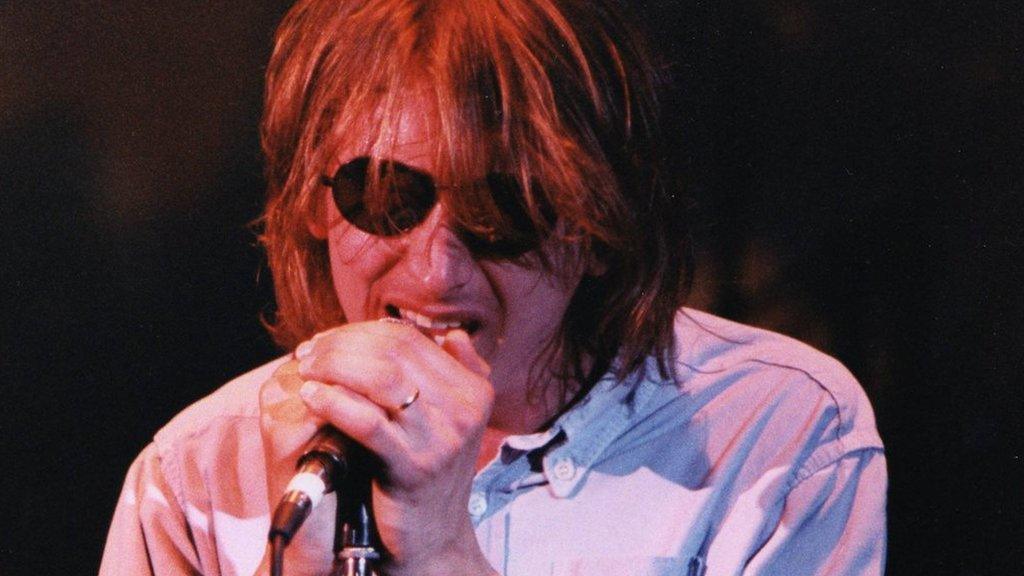

Talk Talk perform It's My Life in Rotterdam in 1984

The year 1986 saw the release of The Colour of Spring, which hinted at their musical ambitions.

Based on the strength of the singles Life's What You Make It and Give It Up, it became the band's biggest album to date.

A year later, Talk Talk settled into an abandoned Suffolk church to begin working on their fourth LP.

When they emerged 14 months later, it was hard to believe it was the same band.

Drawing on ambient textures, jazz-like arrangements and stunning orchestral arrangements, Spirit of Eden is a meditative, melancholy six-song suite that's as downbeat as it is breathtaking.

"It's an engrossing, modern 'head' album, the kind of recording that Pink Floyd never became heavy enough to make," said The Times in a typically enthusiastic review.

"I'd never heard music that dynamic while being organic," wrote Elbow's Guy Garvey, who named Spirit of Eden his favourite album in a recent edition of Q Magazine.

"It's such a brave record. To this day, I can hear its influence."

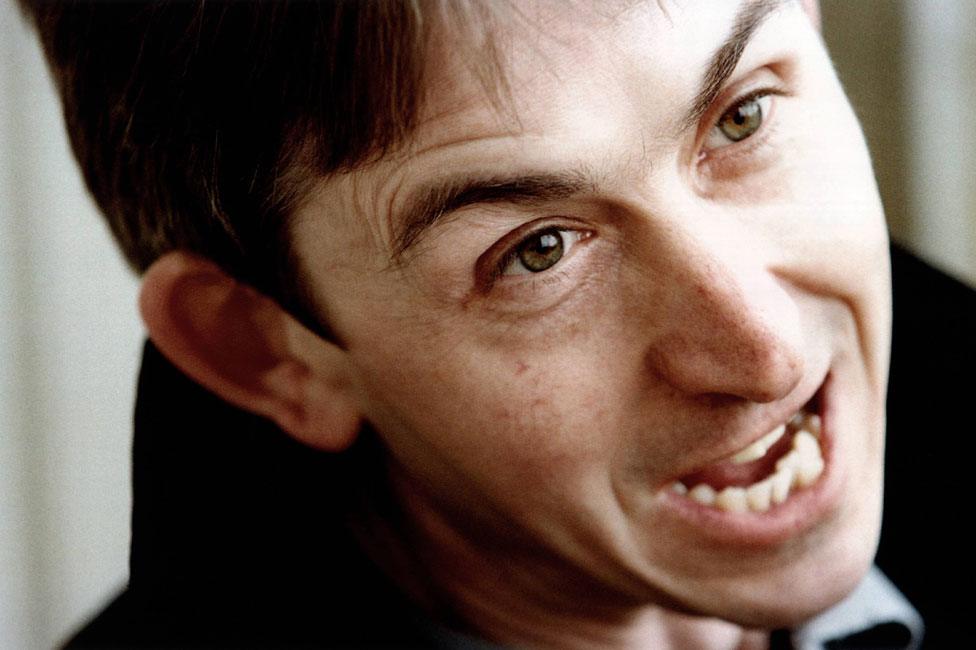

Hollis released a solo album in 1998

The record performed poorly with audiences, however. EMI deleted it after three months and promptly dropped Talk Talk from their roster.

Re-signing to Polydor, the band released one further album - the equally ambitious Laughing Stock - before quietly dissolving.

"There was no big split," Hollis later told The Times. "By the end, everything was so loose that walking away didn't seem like a wrench. We'd reached an end point."

Hollis waited eight years before releasing his first, and only, solo album. Self-titled, nuanced and delicate, it was recorded with just two of microphones strategically placed to capture the musicians' every inflection, from gently caressed guitar strings to the creaking of their chairs. It ends with two minutes of analogue tape hiss.

Perhaps he was always travelling towards silence. "Before you play two notes, learn how to play one note, and don't play one note until you've got a reason to play it," he said in 1998, shortly before retreating from public life altogether.

But there's something uniquely inspiring about a musician who puts a full stop on their career.

There are no second-rate comeback albums or awkwardly staged reunions to taint Talk Talk's legacy. And that's presumably the way Hollis wanted it.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published26 February 2019