Do digital echo chambers exist?

- Published

It’s often said that social media is one of the primary causes of social divisions today - but could it be that actually it’s also a force for good?

A common, and ostensibly common sense, assumption about the era we are living through is that social media is a primary cause of polarisation.

I have often endorsed this idea, whether explicitly or implicitly, during my time at the BBC. Twitter has generally struck me as the industrialisation of confirmation bias. Facebook, a softer version of the same. And other platforms, such as Instagram, similar.

But this claim - that our digital media habits are an exercise in the lazy endorsement of our prejudices - is itself lazy and full of prejudice.

Asked to do a report on the link, if there is one, between social media and polarisation, or social fragmentation, as part of the BBC's Crossing Divides season, I surveyed the academic literature. You can watch our report from the Six o'clock News bulletin with some brilliant young people who met on a Facebook group called The Cabinet.

Challenging the idea of filter bubbles and echo chambers

Most of the academic work in this area points to the complexity of that link, and resists a clear causal connection. Indeed, for the most part, it comes down against the idea that the online world is full of echo chambers.

The abstract for this commonly cited article, external in the journal Public Opinion Quarterly, by Seth Freeman, Sharad Goel and Justin M Rao, puts it succinctly:

"Social networks and search engines are associated with an increase in the mean ideological distance between individuals", the authors write. "However, somewhat counter-intuitively, these same channels also are associated with an increase in an individual's exposure to material from his or her less preferred side of the political spectrum".

They go on: "The vast majority of online news consumption is accounted for by individuals simply visiting the home pages of their favourite, typically mainstream, news outlets, tempering the consequences - both positive and negative - of recent technological changes."

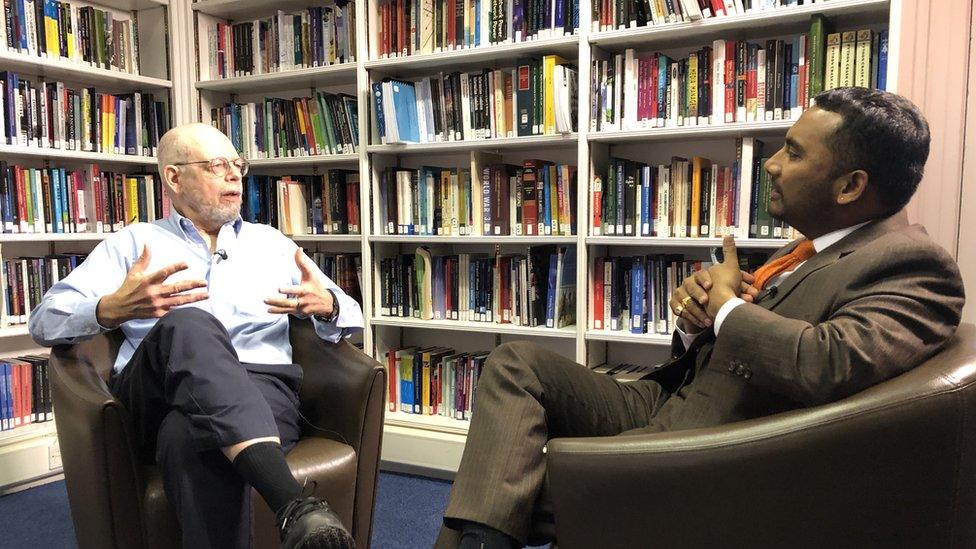

Last week, I went up to Oxford to visit Dr Grant Blank. His most recent work has examined, as he puts it, "the myth of the echo chamber., external"

In an important paper,, external published with Elizabeth Dubois in the journal Information, Communication and Society, Dr Blank concluded "social media and [the] internet [are] not [a] cause of political polarisation."

Dr Grant Blank at the Oxford Internet Institute has examined what he calls "the myth of the echo chamber"

Their findings are striking. In an interview, Dr Blank gave me a nuanced account of our digital behaviour. He told me, "one of the characteristics of the internet is that it has created a very large, complex media environment that includes not just social media but also print media, television, radio, and online media of various types, including online copies of print media - as well as specialised online media.

"And if you look at that entire multi-media environment what you find is people are not in echo chambers, that people are not locked into groups of like-minded people all thinking the same thing and all talking the same way."

I asked him specifically about that alleged link between social media and political polarisation.

"You can find a relationship between social media and political polarisation if you look only at social media," he said. "If you look, in other words, at Twitter or you look only at Facebook. But in a complex, multi-media environment - which is the way people live now because of the internet - you don't find that, you find people consuming a lot of media.

"You find people interacting with others who have varying points of view, changing their minds, encountering contradictory information, checking information that they find in social media. It turns out, if you look at media generally and you ask people what media do you trust, and then you rank the media in terms of trust, social media is at the very bottom of trustworthiness in terms of news."

At this point he returned to a familiar argument: "In Britain it turns out the top [i.e. most trusted] is television. Probably due to the BBC… but television, print media, online media of various kinds are all higher than social media in terms of trust."

BBC Crossing Divides

A season of stories about bringing people together in a fragmented world.

Academics in this field do, however, accept that there is an element of prejudice reinforcement on some social media channels. They just add that you're more likely to encounter different worldviews than in an era where you mainly read The Daily Mirror, say, or watched mainly CNN.

Social media has an effect on the ignorance or knowledge of a citizenry that is, it turns out, nuanced and complicated. It certainly gives prominence and oxygen to fringe views that would once have struggled to get a hearing. It ostensibly democratises opinion, by equalising the format in which the US President and some conspiratorial nutter opine: both have 280 characters on Twitter.

And for those who want to indulge niche interests, whether political or otherwise, it creates digital wormholes in which you can lose yourself.

Why should the idea of echo chambers, or the associated theory be so seductive and popular? Partly because Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble, is an engaging speaker., external Also, because there are times when we all feel like our social media feeds slant in one particular direction. And, ironically, because the idea of echo chambers and filter bubbles has bounced around social media, gaining traction there.

Maybe some platforms, such as Twitter - which is the preferred receptacle for verbose journalists and politicians - are more prone to uniformity of outlook for some users. Which might explain the final reason echo chambers have become part of the prevailing orthodoxy: people like me have parroted the idea without surveying the academic literature.

Journalism and academia: that's one divide that should be crossed more often.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from Radio 4.