Lee Krasner: Will Gompertz reviews the 20th Century's unsung artist

- Published

Lee Krasner was in Paris when she received the call.

It was sometime around midday on Sunday 12 August 1956. The American artist had never been to the French capital before, although she'd been inspired by others who had, namely Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh.

She was not impressed by the Louvre, the scale of which she found overwhelming and the art "unbelievably bad". The news she was about to receive would be much, much worse.

Lee Krasner, Mosaic Table 1947

There had been an accident back home, she was told. Her husband, who had stayed at their East Hampton house on Long Island, New York state, while she went on her European adventure, had crashed his convertible car at 10pm the night before.

There were two female passengers in the overturned vehicle. One had been killed, the other, Ruth Kligman, was OK.

And then this: the driver, the man she had married 11 years earlier, the painter she had supported through all his artistic difficulties and battles with alcoholism, the one person on Earth with whom she truly connected, had not survived.

Jackson Pollock was dead.

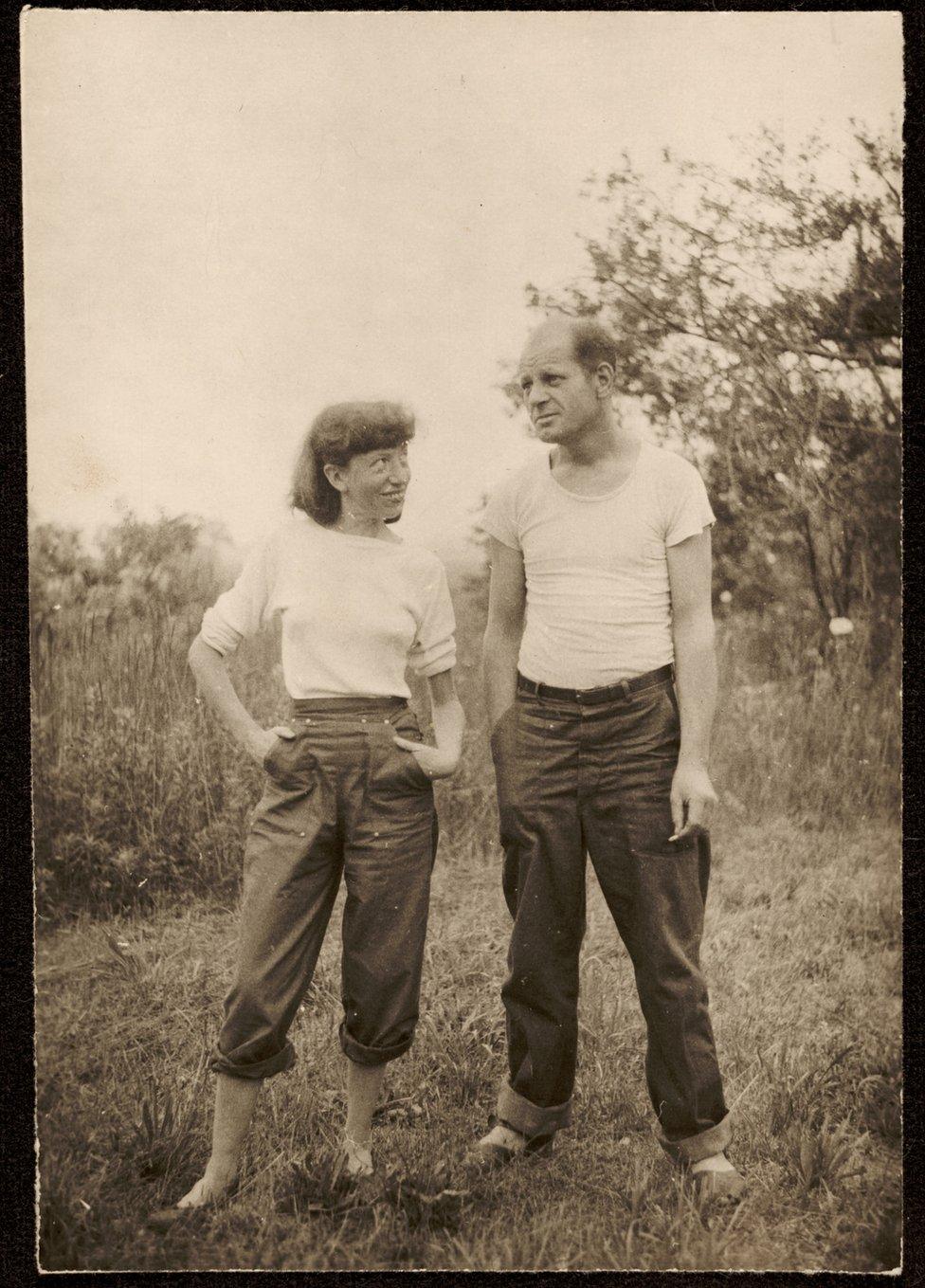

Lee Krasner, who was in the shadow of her husband, celebrated artist Jackson Pollock, seen here in Springs, 1946

When they first met, in the early 1940s, Krasner was considered the more accomplished artist. But ever since Mural (1943), Pollock's huge, ground-breaking, abstract painting, it had been her husband's work that garnered all the attention. The shadow his fame had cast over her own career as a significant player in post-war American Expressionism looked as if it would only grow longer with his death.

And so it did. Jackson Pollock became a mythical figure: immortalised in Hans Namuth's photographs, romanticised as a troubled genius, and fought over by billionaires and institutions desperate for a signature piece. (It's amazing what dying will do for an artist's career.)

Meanwhile, Lee Krasner went about her business as an artist, while also taking on the additional burden of looking after her deceased husband's estate. Legal tussles, legacy issues and authentication meant this was no easy task

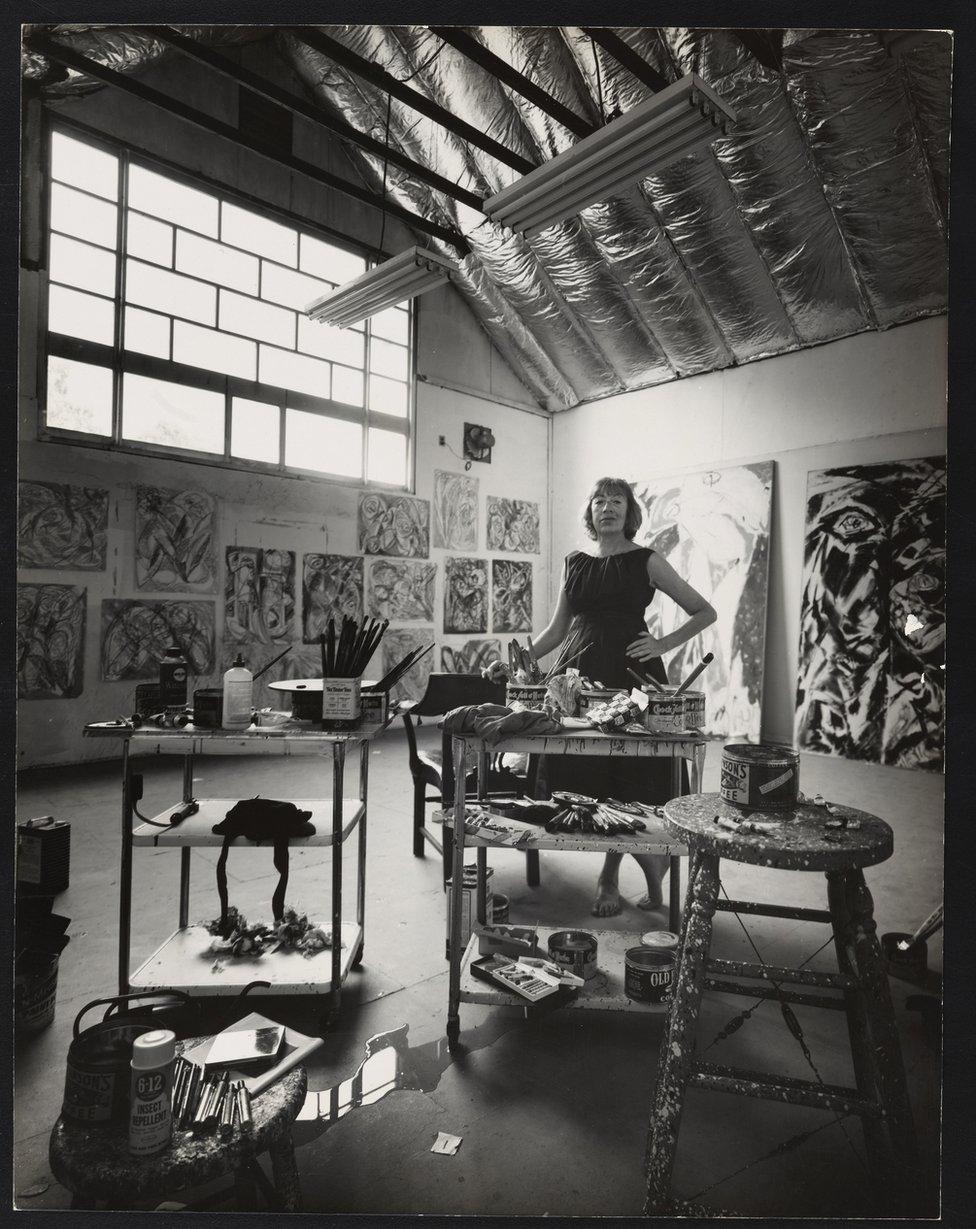

Hans Namuth took this photograph of Lee Krasner in her studio in 1962

True, she was exhibited, but there tended to be a Jackson shaped elephant in the room. Either her work was seen in the context of his, or he wasn't mentioned at all. Neither approach was satisfactory. She remained in his shadow even after her death in 1984.

That was 35 years ago. Now, at last, there is a confident, intelligent exhibition, presenting Lee Krasner in her rightful position as one of the most important painters of the 20th Century.

Lee Krasner, Bald Eagle, 1955

There is no need for Jackson denial or comparison. His presence in her life is evident. It can be seen in material form in her collage Bald Eagle (1955), which contains paint splattered fragments of a Pollock picture. It can be felt, too…

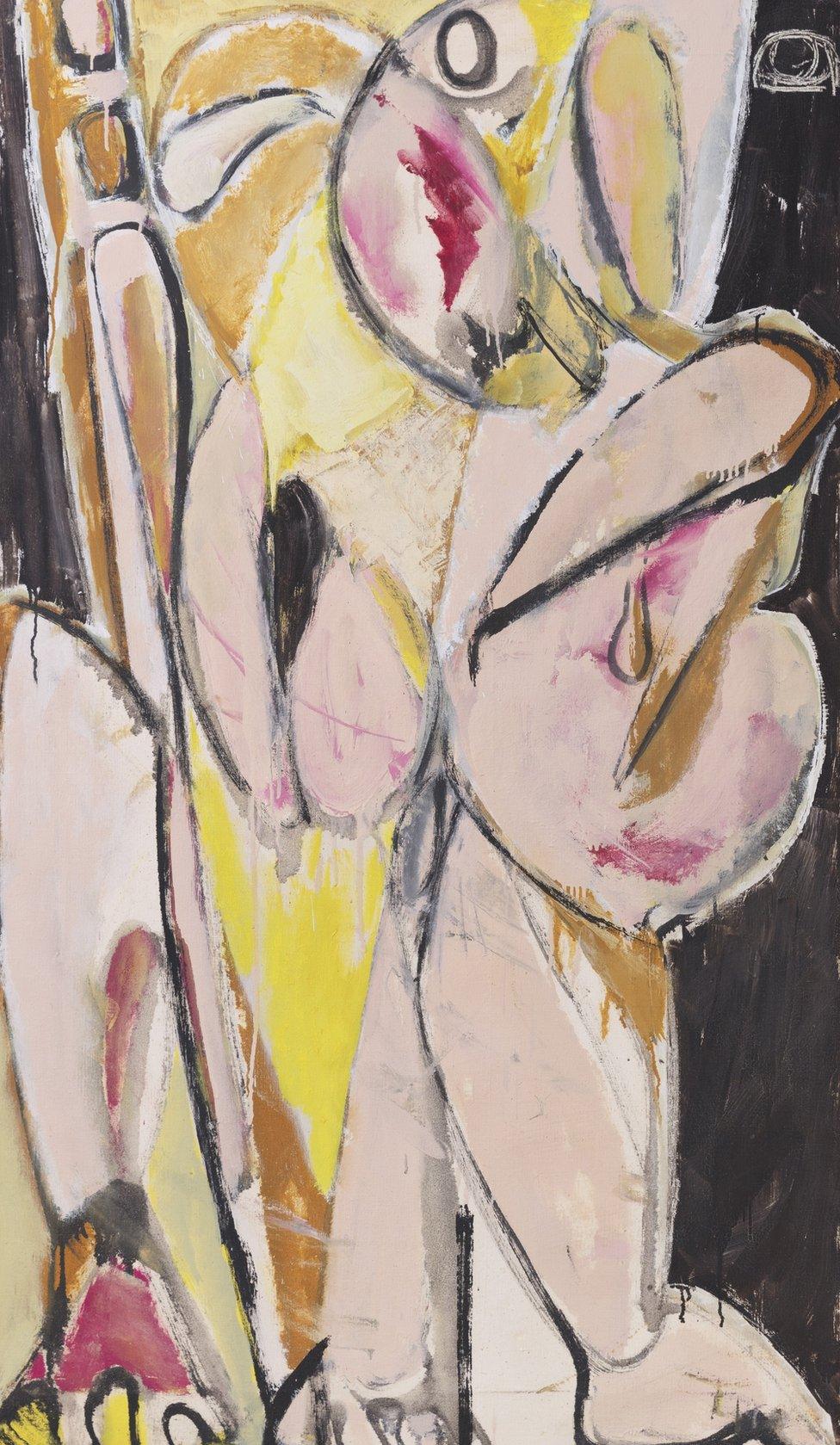

There is a small, dark room in this exhibition, in which hangs a series of four large paintings, inspired by Picasso's famous Les Demoiselles Avignon, external (1907). The first is ominously called Prophecy (1956). Krasner painted it in the summer of 1956 before her trip to Europe, when her husband's drinking was as bad as the state of their marriage. It is a bulbous, fleshy, awkward image: both anxious and hopeful, menacing and heavy. She said it "disturbed me enormously".

Lee Krasner, Prophecy, 1956

A few weeks later, Pollock was dead. Krasner returned and immediately continued with the series, saying: "Painting is not separate from life. It is one. Do I want to live? My answer is yes - and I paint."

The three subsequent works - Birth (1956), Embrace (1956), and Three in Two (1956) - are deeper, angrier, magnificent paintings. If you want to know what raw pain and loss feel like, spend a few minutes in this room. They are technically accomplished, complicated pictures, delivering an emotional charge that you won't quickly forget.

Lee Krasner, Three in Two, 1956

Three in Two is like a Tarantino movie but without the humour. It is full of blood, gore and anger; a reflection on Pollock's fatal car crash perhaps, and the fact that there was a third person in their marriage - his lover, the sole survivor of the accident, Ruth Kligman.

This room is the pivotal point of the exhibition. It is the apogee of Krasner's investigation into Cubist techniques and ideas, which started with her Nude Study from Life (1938), produced while she was a student of the German modernist Hans Hofmann. One glance at the wall on which this group of early drawings are exhibited and you will know why Hofmann said she was one of his finest students.

A 19-year-old Lee Kransner - as she was then - taking her first tentative steps as an artist, inspired by the en plein air style of French Impressionists like Claude Monet

By her early 30s Krasner has learned the art of Cubism, and how Pablo Picasso and George Braque used fragmented planes and negative space to represent a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional canvas

Krasner, like her late husband Jackson Pollack, finds a way into pure abstraction and a career of studying light, form, colour and scale

She quickly moved into abstraction, producing a series of "Little Images" in the mid-1940s, including the excellent, Miro-like Abstract No. 2 (1946-48) and the blood red Untitled (c. 1948-49).

There are misses among the hits, as you would expect from an artist who refused to settle on a single style, announcing rather grandly: "I am not to be trusted around my old work for any length of time."

Her mid-1950s collages are a mixed bag. Burning Candles (1955) fails to settle as a composition and is strangely irritating to look at, while Blue Level (1955) is admirable for its bravado and risk-taking, but didn't do it for me. Unlike Bird Talk (1955) and the aforementioned Bald Eagle, both of which would be very welcome on one of my walls.

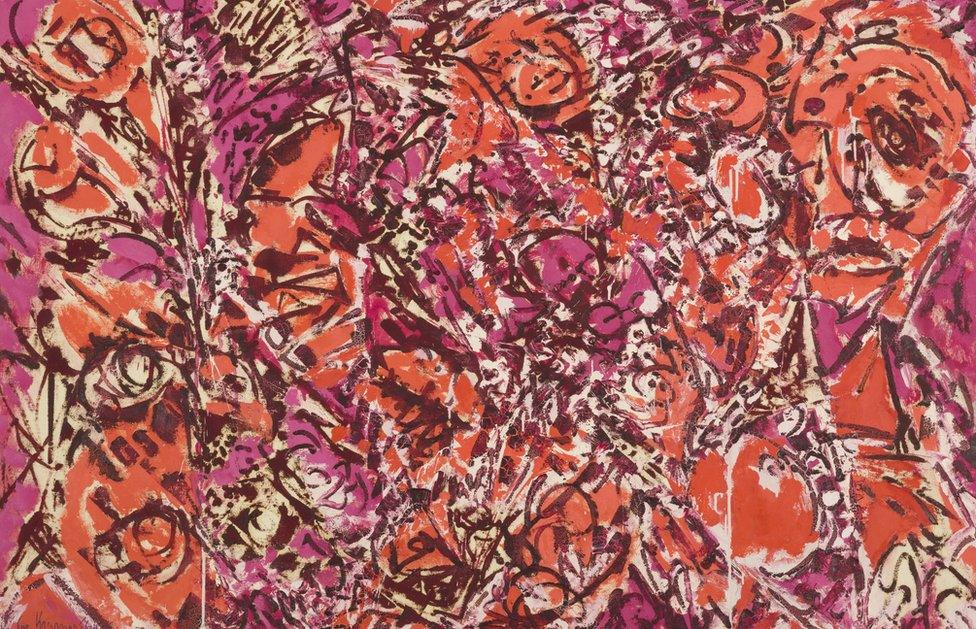

Lee Krasner, Another Storm, 1963

As would any one of her giant abstract expressionist paintings from the mid-'60s. Unfortunately I don't live in a mansion or own a museum, or anywhere with the sort of wall space they'd need. But London's Barbican Art Gallery does, and they fill its central galleries, which, for once I am pleased to say, are pepped up with a little natural light.

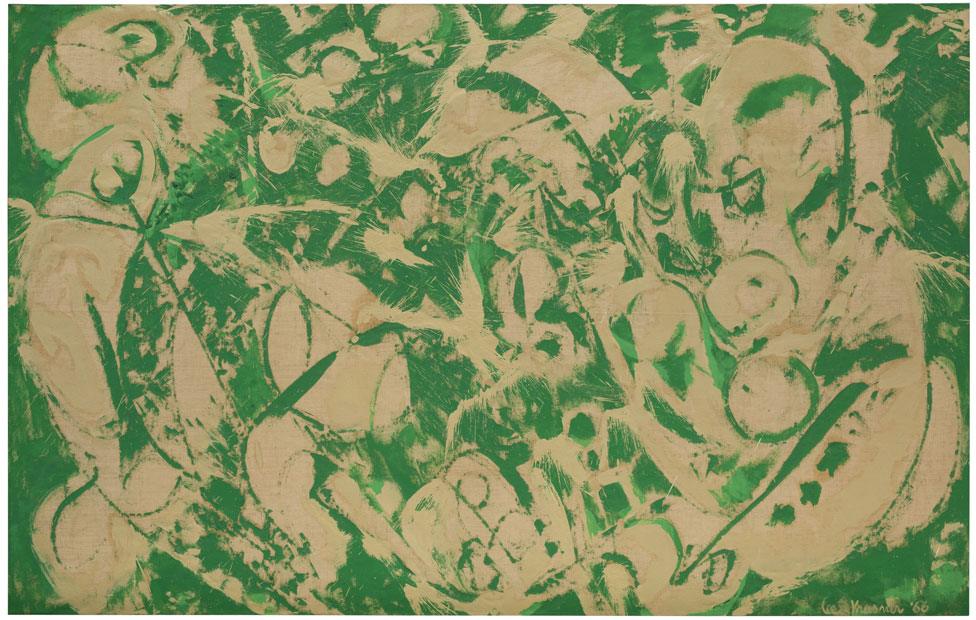

Lee Krasner, Siren, 1966

Here we see Krasner on an operatic scale, painting huge canvasses with looping strokes and a conductor's sense of rhythm. There is not a dud among them: painting after painting sings out from the walls in harmonious tones of red (Another Storm), orange (Courtship), green (Siren), or pink (Combat).

Lee Krasner, Icarus, 1964

Krasner said she liked jazz. You can not only see that in these paintings, you can hear it. Imagine seeing them alongside Kandinsky's series of Compositions - you'd need earmuffs!

They are a wonderful way to end a wonderful show. Lee Krasner was full of colour and ideas and life, as is this exhibition. Do go and see it if you can.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external