Amol Rajan: What kind of internet do you want?

- Published

The race is on to shape the internet around the globe

In recent months I have been influenced by a paper on The Geopolitics of Digital Governance, external by two University of Southampton academics, Kieron O'Hara and Dame Wendy Hall. The paper popularised, but didn't invent, the idea of the "splinternet" - namely, that there is not one internet, but four.

These four internets are, broadly: the open, universalist version envisioned by the web's pioneers; the current, largely Californian internet dominated by a few tech giants (Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook); a more regulated, European internet; and an authoritarian, walled-garden approach, of the kind seen in China, which has its own tech giants (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent).

Most of the stories that I end up covering for BBC News chronicle various attempts to navigate from the second (Californian) internet to the third (European, regulated).

What you might call 'the Southampton argument' is based on an irresistible and irrefutable claim: that there is no one internet, applicable to all humanity, and arising in all places; rather there are several iterations of this revolutionary technology, of which the four articulated by our friends in Southampton are simply the most prominent.

Kieron O'Hara and Dame Wendy Hall from Southampton University developed the idea of the 'splinternet'

As our species grapples with the unprecedented disruption, life-improving possibilities, and terrifying potential harms of digital technology, a battle is raging to shape the future of the internet. According to the best estimates, last year was the moment that - for the first time - more people were online than off-line.

That means almost half of humanity is still up for grabs. What kind of internet will these people, around three billion of them, come into?

In the past year, several articles, such as this Economist briefing, external, have noted that the companies which dominate the internet today are desperately battling for the attention of those three billion future users.

This is the context in which Sir Nick Clegg is speaking in Berlin on Monday.

Europe's leading role

In his first speech and interview since joining Facebook, Sir Nick chose Brussels as his location. On Monday, he chose the German capital. It isn't mere Europhilia dictating his travel plans, as if the former trade negotiator were trying to relive his youth. It is, in fact, cold, hard commercial need.

Facebook knows regulation is coming. It has noticed that most of the smart thinking on regulation is coming from Europe. It wants to shape that regulation before that regulation shapes Facebook.

Mark Zuckerberg hired Sir Nick to explain Facebook to Europe and Europe to Facebook. In the past two years, we have seen what amounts to quite radical shifts in the relationship between technology companies and the law, emanating principally from Brussels.

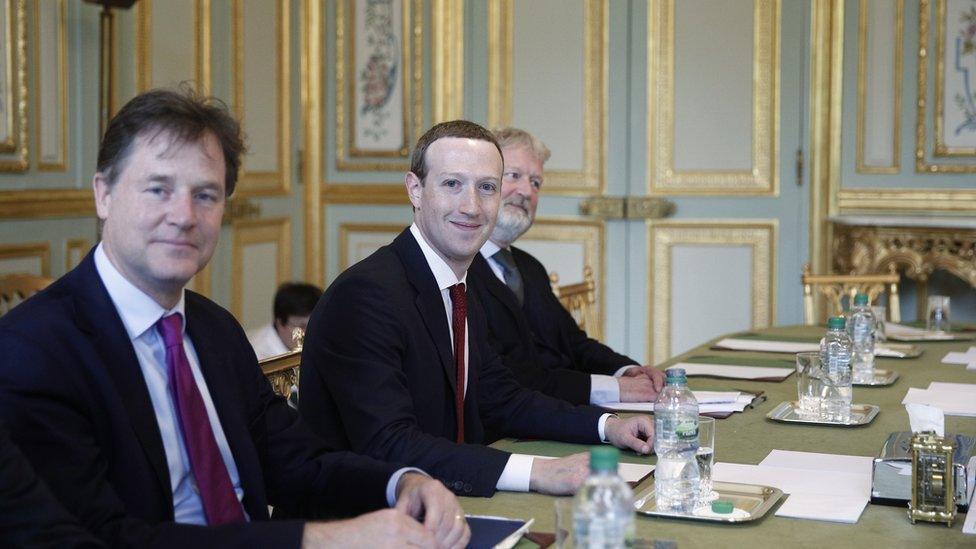

Facebook's Clegg, Zuckerberg and Lord Richard Allan, president of public policy EMEA - and Clegg's predecessor as Liberal Democrat MP for Sheffield Hallam

GDPR, the name for new data rules, is generally thought to have shifted power back to consumers (albeit at the price of constantly clicking on pop-up boxes on various websites). The most powerful blow to Google's dominance of various sectors has come from the Competition Commissioner in Brussels. And Britain's Online Harms White Paper, external, which boasts of implementing the toughest internet laws in the world, was cooked up between the Home Office and Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport in Whitehall.

This amounts to an onslaught. Sir Nick is being paid to deal with it on behalf of the tech giant. The opening line of his speech will assert that Facebook actively seeks regulation. It wants new rules on privacy, electoral law, hate speech and data portability. And it is quite happy for those rules to be devised in Europe.

Why? Culture, mainly. I have written at length on this blog about the tech-lash, a phrase Sir Nick is using today, and the clash between the world views of Silicon Valley and Europe.

A libertarian culture that prizes autonomy over order and is profoundly sceptical of government is often ill-suited to devising smart new legislation of a quickly evolving sector.

China, meanwhile, has a completely different set of norms about what the citizen's experience of the internet should be.

But in much of Europe, not least Brussels and Berlin, there is a presumption that effective legislation is possible, plausible, and totally necessary. So Facebook is quite relaxed about these new rules coming from Europe rather than, say, the White House of a President they fear is temperamental.

Shaping the future

Or indeed from China, which Facebook understands less well and has yet to penetrate commercially in the way it would like.

Plus, the social media giant is an also-ran when compared with the Chinese tech giants of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent.

Though it has yet to seep into public consciousness, and escape the land of policy wonks, a Cold War is already underway between the US and China, with trade and technology being the two main fronts.

How technology companies are being mobilised by the American and Chinese governments as part of this war is not fully clear. That said, in America, the tech giants are fiercely independent of, and yet in political friction with, the government. In China, they are in the lap of government.

The tech giants Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent are dominant in China

Europe, which lacks a tech giant, and has that culture of favouring regulation, is therefore unusually well placed to plan the future of the internet. That future is one where the new users - those transitioning from off-line to online - are generally poorer than today's users; much less likely to speak English; and almost certain to be mobile-first (as opposed to laptop or tablet).

Though they have less money, they are a juicy commercial proposition for American corporate behemoths who are thinking long-term, as is their wont. Sceptics might point out that with the political heat turned up to maximum in Washington and parts of Europe, Facebook and Sir Nick are trying to grasp the initiative so that they are not broken up: a prospect that is being threatened with ever greater frequency.

Hyper-alert to such threats, conditioned by a long-term, even epochal, mindset, and concerned about the authoritarian turn in Asia, Facebook is determined that the future of the internet is shaped more in Brussels and Berlin than Beijing.

Though they cast themselves as a global community above mere politics, Sir Nick's second consecutive speech in Europe, and his accommodating approach to new laws, shows a company evolving from a libertarian to a liberal disposition.

Facebook is not an apolitical entity championing universal human values. It is an unprecedentedly powerful corporation, born of and conditioned by specific historical circumstances, and led by liberals with their own particular experiences and affiliations. Sir Nick's fondness for Europe just happens to be highly expedient.