Cindy Sherman: Will Gompertz reviews the artist's show at the National Portrait Gallery ★★★★☆

- Published

Once upon a time there was a little girl in America who liked to dress up. She had a big box full of prom outfits and high-heeled shoes that went clickety-clack when she walked. But the curious child was soon bored by it all.

So, one day she crept down into the cellar without anyone knowing and opened a leather suitcase full of her grandmother's old clothes. She picked out a dress and a blouse and tip-toed back to her bedroom.

She put them on and stood in front of her mirror.

Oh my! What a sight!

But, oh dear.

It wasn't quite right.

Something was missing. Make-up, of course!

Off she went and found some foundation and eyeliner and applied them just as she'd seen Granny do a thousand times before. And then she had the most perfect idea! She took off her socks and stuffed one into either side of her waistband.

Now, when she stood in front of the mirror, the transformation was complete. She was Grandmother! Right down to her bloodless cheeks and sagging breasts. The little girl was thrilled and swore to herself that one day she would do it all over again.

And she did, that 10-year-old kid.

In fact, she turned dressing up into an art form. Her photographed impersonations hang on the inscrutable white walls of the world's most prestigious modern art museums. They sell for millions of dollars.

She is revered. By Madonna. And lots of other people who are less famous. For good reason.

Cindy Sherman is a very fine artist.

She started out as a painter when a first-year art student at the State University College, Buffalo in 1972. By the time she left in 1976 she was knee-deep in the biggest dressing-up box known to man: the costumes and customs of American popular culture.

It is at this point we first meet Cindy Sherman in the National Portrait Gallery exhibition: as a 22-year-old ingénue experimenting with the three components that would become the basis of her work: photography, identity, and portraiture.

She went from painting to performing to posing in photographs, which would almost exclusively always be taken by her of her.

They are not selfies as we now know them. They are the opposite.

Cindy Sherman does everything she can to remove her own personality from her pictures.

Just as she did as a child when dressing up as granny, her aim is a sort of possession: a complete embodiment of someone else.

She started tentatively in 1975.

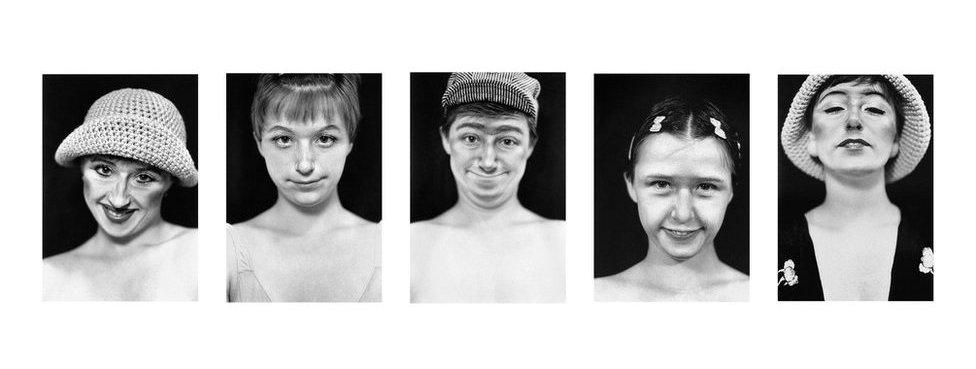

In Untitled A - E, 1975, a young Cindy Sherman changes her facial expressions to create different characters

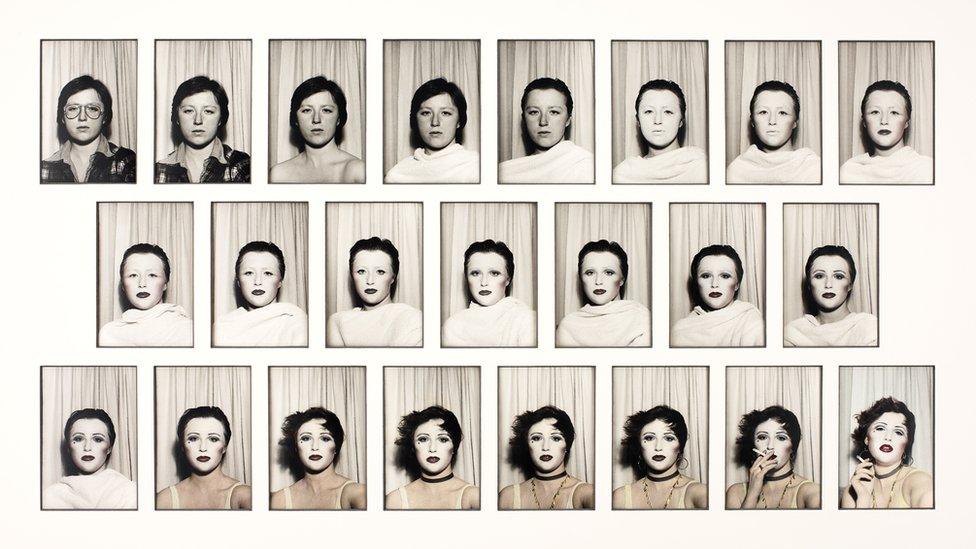

Over 23 images in Untitled #479, 1975 we see a gradual transformation

Initially by pulling faces in Untitled A-E, and then morphing into three different alter-egos in Untitled #479, in which her appearance and persona change through 23 consecutive images. (Sherman's frequent use of the title Untitled for her work is part of the picture: it suggests ambiguity, an openness to interpretation.)

Seeing this early work will be manna from heaven for Sherman nerds.

Less so for the uninitiated, who will recognise it for what it is, work in progress.

The gear shift happens in Line-Up, a series of images made shortly after she graduated in which she fully indulges her dressing-up box fetish. Wearing a variety of costumes, wigs, masks and hats, Sherman poses in front of her camera with her left foot and shoulder slightly forward.

She had found her defining aesthetic: a single image of her in disguise.

The Line-Up series revealed the chameleon-like nature of the artist's work

Not much to build a very successful 44-year career from, one might think. But then, one might not think like Cindy Sherman, a baby-boomer brought up on a diet of Hollywood movies and glossy magazine advertisements.

She saw that identity was an elastic and malleable construction; a moveable feast on which she could dine.

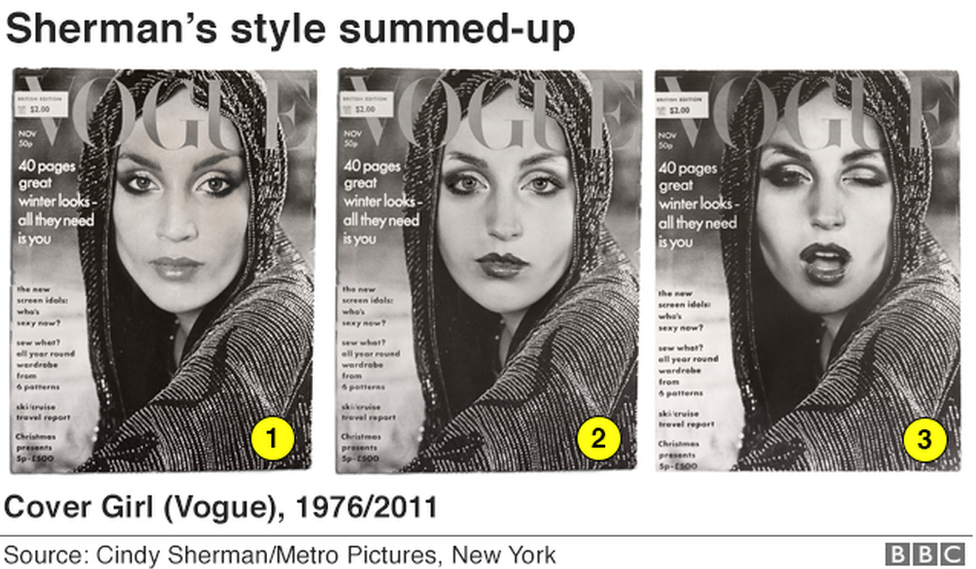

1. Sherman's Cover Girl series (1976/2011) is rooted, like all her work, in the visual language of popular culture. In this instance she appropriates an image of a real person, the model Jerry Hall on the front cover of Vogue magazine.

2. The illusion begins. Sherman slyly possesses the character to create a believable but illusory persona; questioning the relationship between subject and creator.

3. The subversion. The artist employs the vocabulary of fashion photography to mock its tropes: a fake image highlighting the artifice present in the original.

The high point of this exhibition, the high point of any Cindy Sherman show, are her 69 black & white Untitled Film Stills, produced between 1977 and 1980 (she only stopped because she "ran out of clichés").

Entire PhD theses have been written on these staged photos made shortly after the artist moved to New York, a city she found so intimidating she took to going out disguised with boyish hair and armed with a mean attitude.

That sense of being an isolated, vulnerable woman subjected to the male gaze played a part in this break-through work with its distinctly Hitchcockian mood.

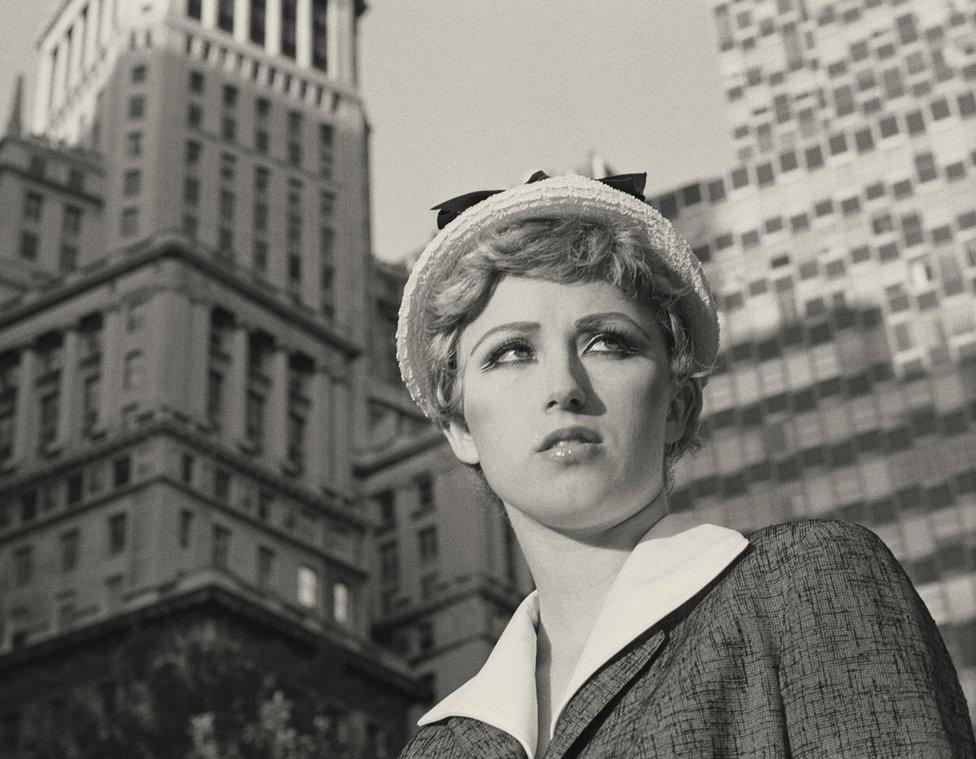

Sherman's entire Untitled Films Stills series goes on show for the first time in the UK (Untitled Film Still #21, 1978)

Sherman first gained critical acclaim and fame through her beautifully composed Untitled Film Stills series (Untitled Film Still #15, 1978)

Each staged shot consists of Sherman adopting the role of a fictional female protagonist in an unnamed but faintly recognisable film from the '50s or '60s. She is alone and exposed; caught on camera at the moment just before or immediately after an unspecified dramatic event.

They are ominous and ambivalent and like crack cocaine for the imagination. Although you know nothing of this woman, or her circumstances, or her location, you cannot help yourself speculating about the scenario. Who is she? What's going on? She seems so familiar…

And before you know it, you've invented a story, a film even, around the artist's artifice. At which point you look up and realise you've barely started the exhibition.

Untitled Film Stills is but one of more than 20 different series of portraits by Cindy Sherman in this show.

Some are better than others.

Her pornography-inspired Sex Pictures (1992-96) in which she used plastic medical models in a way the manufactures probably hadn't envisaged are grotesquely good.

The Chanel series is less successful. And Flappers (2016-18), where she appears disguised in the fashions of the 1920s, are weak in comparison to the biting satire that is a hallmark of her best work.

Untitled #574 by Cindy Sherman, 2016, which is part of Flappers series

But these are occasional misses in an exhibition packed with hits by an artist who knows better than most that, ''Through a photograph you can make people believe anything."

Cindy Sherman as herself

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external