Dame Paula Rego: Will Gompertz reviews Obedience and Defiance show in Milton Keynes ★★★★★

- Published

It is June 1998 and Paula Rego is furious. Her people, the Portuguese people, had not turned up in sufficient numbers to vote in the recently held national referendum to change the country's conservative abortion law.

The London-based artist was appalled.

As someone who had endured the life-threatening brutality of back-street abortions she was dismayed the Portuguese - particularly the women - had passed up the chance to legalise the termination of pregnancies on request up to 10 weeks from conception.

The wholly avoidable deaths and distress suffered by thousands of women resorting to illegal abortions every year would continue. No wonder her father had said Portugal was no place for a woman, before packing off his talented teenage daughter to England to hone her painterly skills at The Slade School of Fine Art in London.

She sat in her Camden Town studio and fumed, determined to do something about the situation; to change public opinion back home; to make a difference. Which she did (the law was changed in 2007). By doing what she always did when overwhelmed with anger. She created a group of troubling, ominous images.

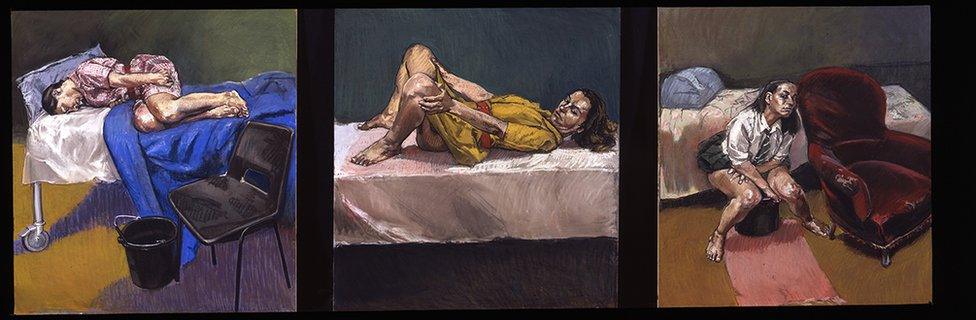

Paula Rego's abortion series began with this dark and searingly honest Triptych, 1998

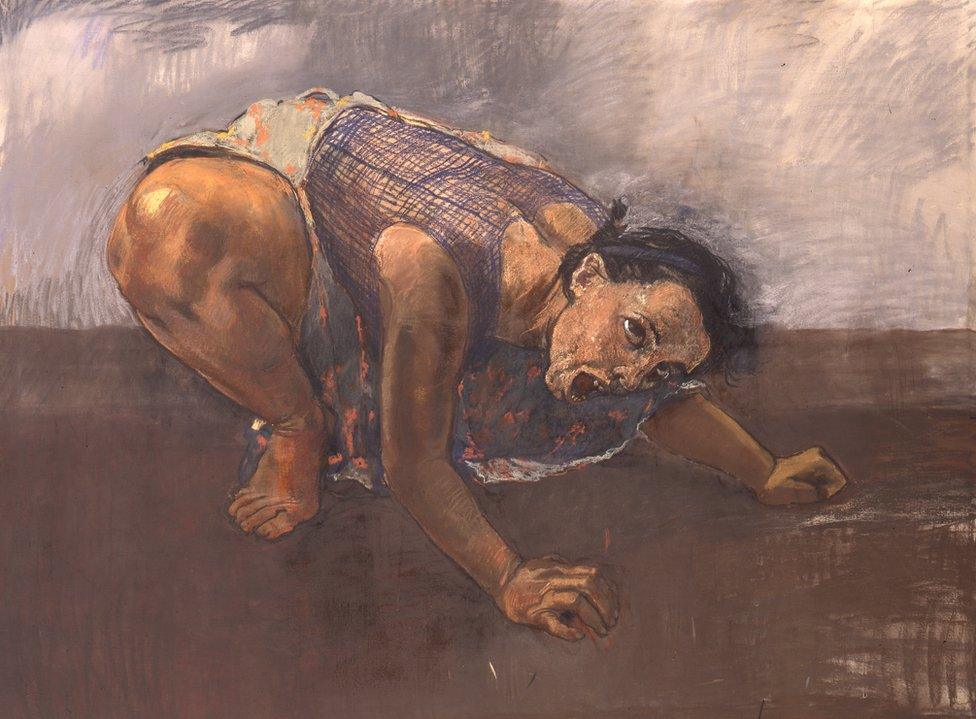

Rego's abortion pictures are as confrontational and direct as a John Humphrys interview.

There's no flim-flam, no tip-toeing around the topic: she gets straight to the point… which is darkly ambiguous.

She is both explicit and vague.

There is an equivocation that makes for uncomfortable viewing. Her truth resides in psychological complexity however awkward it may be. To Rego, the grim reality of a back-street abortion is not intellectually straightforward. It is not simply a case of a bad thing happening.

Look at any of the imposingly large pictures she made in this series and you will be disturbed.

There is an uneasy eroticism bound up in the pain and the squalor. The schoolgirls and young women depicted challenge the unseen figure with a physicality and preparedness. Have they girded up their loins in anticipation of an impending termination or something else?

Welcome to Paula Rego World, where there is always something nasty in the woodshed.

With Untitled No. 5, 1998 and others in her abortion series, Paula Rego says "they are not pictures of victims"

To see a Rego picture is to be thrust into the midst of a sinister gothic drama. A fat-ankled lady wearing a walnut-like skirt bends down to lift a prone dog by its front legs in Snare (1987). She leans forward as if to give the animal a sensual kiss, a red rose in the foreground suggests love. Near it, a crab lies powerless on its back mirroring the dog's vulnerability. It is rich with symbolism and menace.

It is also technically very good.

The red-to-brown palette has the tonal harmony of Picasso's impeccable portrait of Gertrude Stein (1905-6). The suggested volume of the figures is as convincing as a mirage in the desert. And the weight the lady's legs bear, and pressure of the grip with which she holds the dog, are palpable.

It is a very good figurative painting.

Snare, 1987 is a key work full of symbolism - with the skirt concealing "secrets"

It marks the moment Rego found her signature style.

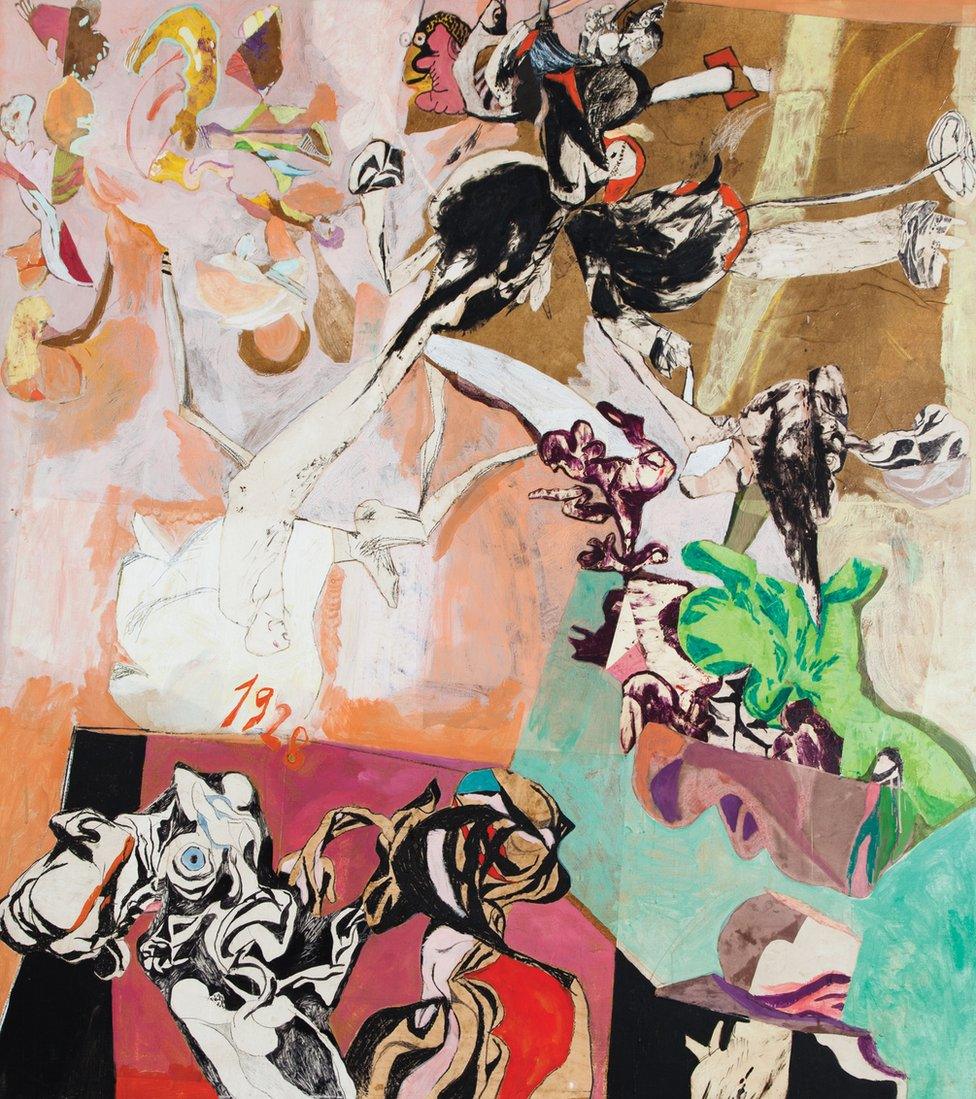

There had always been a strong narrative element to her work, whether back in the 1960s when she was making cut-up collages like The Imposter (1964) critiquing the Estado novo authoritarian regime in Portugal. Or, in the early '80s with abstracted, cartoon-like paintings such as Red Monkey Offers Bear A Poisoned Dove (1981), lampooning the love triangle she constructed between her husband and her paramour.

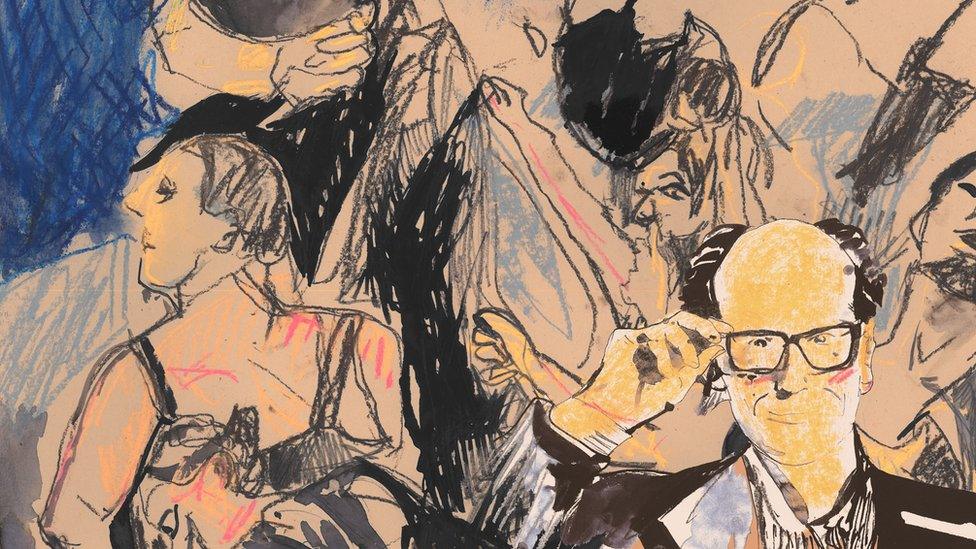

Paula Rego criticised the Portuguese dictatorship in works like The Imposter, 1964

But these were works in progress towards the stylised tableaus and heavy-featured figures that are now instantly recognisable as a Paula Rego. Hers is an idiosyncratic aesthetic heightened later by the use of oil pastel crayons instead of acrylic paint, a mid-career decision made - I am told - in part to help her stop smoking.

The results are impressive.

Turn 180 degrees from the Abortion Series hanging in the central space of the MK Gallery, and there, on the opposite wall, are her Dog Women pictures from the early 1990s.

They were inspired by the French Impressionist painter, Edgar Degas. He was an artist famous for his use of pastels and elevated perspective, from which he portrayed dainty dancers in ballet rehearsals. His representations of a woman's physique and inner life were voyeuristic, with a hint of the dirty-old-man about them. Rego's couldn't be more different.

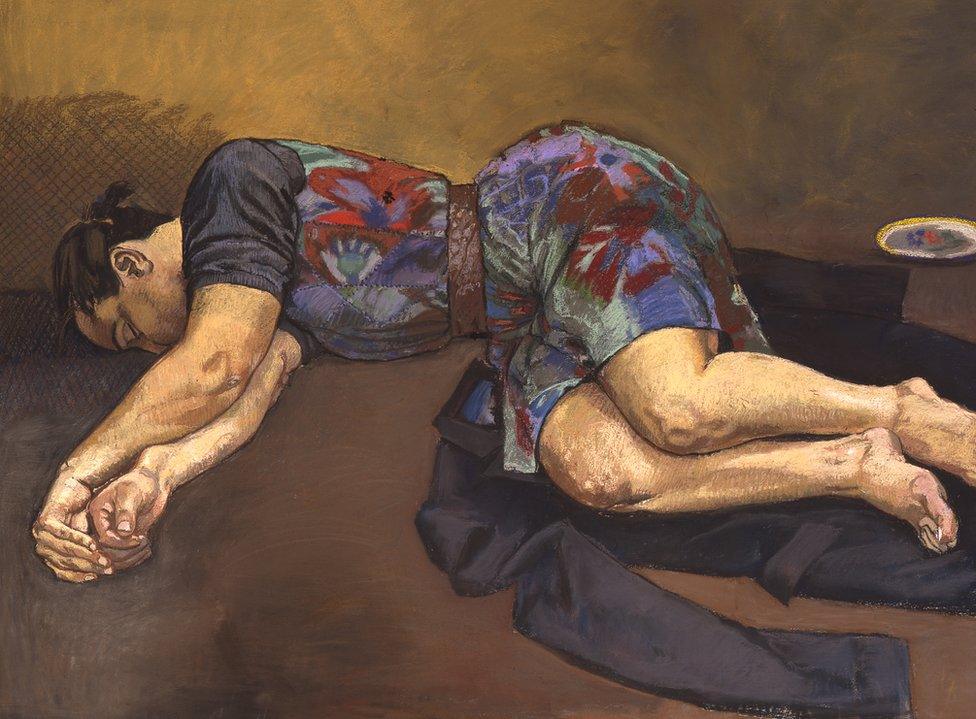

Degas' viewpoint of looking down on the model can be seen in Rego's Sleeper, 1994

Dancers, 1884-1885 by Degas, who influenced Rego with what she says were "his marvellous use of pastels"

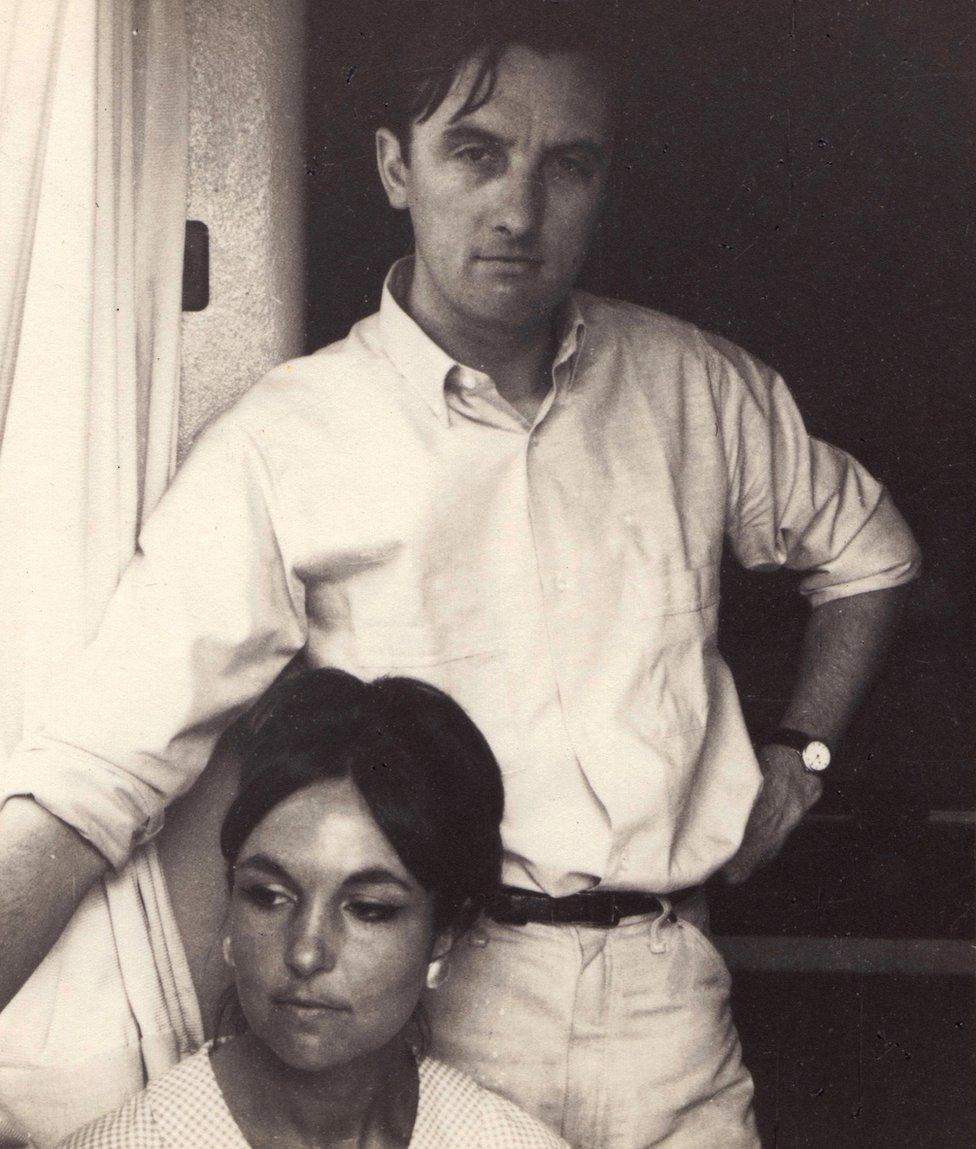

Her Dog Women are more like werewolves; snarling creatures that are both loyal and fiercely independent. The pictures are a response to the death of her husband, the artist Victor (Vic) Willing whom she met while a student at The Slade.

She considered Vic her intellectual and artistic superior, a point of view he was in no rush to counter. His critical eye helped her work develop but petrified his own. Life got complicated. He was already married. She went back to Portugal.

Vic left his wife and went to live with Paula. He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. They both had affairs. Her father died. Vic took over the family business and ran it into the ground. They returned to London, penniless. Paula found a lover to help pay the way. Vic began to paint again shortly before he died.

Theirs was a passionate, painful, profound relationship, which Rego renders in pastel with disarming sincerity. Woman becomes dog-like, part domesticated and part wild animal. She lies on her owner's jacket in Sleeper (1994), is kicked out of bed in Bad Dog (1994), and roars in rage in Dog Woman (1994).

Paula Rego with her husband Victor Willing, with whom she had a passionate but complicated relationship

Paula Rego's belief that "every woman's a dog woman, not downtrodden, but powerful" is reflected in Dog Woman, 1994

But it is in Sit (1994) that Rego captures the specific and the universal of her marriage to Vic with an emotional intensity you won't quickly forget.

The female figure is doing as she has been told, sitting obediently in her chair. Her hands are behind her back, possibly bound. Her feet are crossed in the manner of the crucified Christ. She is pregnant.

She looks up and away at her tormentor, her owner, her lover. She is trapped, subjugated, but in no way tamed. Her eyes blaze with defiance, her body emits power. There is an air of sexuality and violence, love and hate; beauty and the grotesque.

It is a uniquely good picture.

Obedience and defiance are apparent in Sit, 1994, which seems to be a stark metaphor about Rego's marriage

It's not the best image ever created. It is not even the best image Paula Rego has ever created - The Dance, external (not in this exhibition) - is better.

But it is exceptional.

We've seen plenty of male artists picturing woman in myriad different ways, but who else has painted the world from a female point of view in the manner described by Paula Rego?

Louise Bourgeois and Frida Kahlo had similar concerns, and expressed them just as unflinchingly, But Rego's voice is more literary, painterly and poetic in the way of Edgar Allan Poe. She references the Brontë sisters, Edvard Munch, William Hogarth and Francisco Goya.

She is a romantic surrealist with a satirist's cutting edge.

The Duchess of Alba, 1797 was painted by the Spanish artist Goya who influenced the Portuguese-born Rego

The figure in Angel, 1998 is a symbol of female power and strength

Quite why she is not more famous is difficult to fathom. Maybe her gender and style went against her? A bit too much for all those buttoned-up male museum directors whose stripped back modernist tastes ruled the roost for far too long.

Their time has come and gone.

The game is changing.

I can't recall another exhibition season quite like this summer's, when there are so many monographic shows dedicated to female artists being staged across the country.

It brings to mind the female figure in Sit. She knew her time would come. And so it has. It is now.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external