The internet as religious experience

- Published

Can the meaning of life be found in code?

For most of recent human history, by which I mean the last few millennia, social organisation has been rooted in practical faith.

Religion, which departs from philosophy when it gives meaning to this life through reference to a transcendentally different realm, has been the method of settling disputes within local populations, if not between them.

Great cities of antiquity were built around sites of communal prayer, such as the church or mosque; market-places, such as the town square or bazaar; and schools, which were often the venue for religious teaching. These venues generated social capital, creating bonds of mutual trust and affection between people who, despite their differences, needed to rub along.

Today, to paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of the death of God have been greatly exaggerated. In fact, religion is in the ascendant across the world, not least because the religious have more babies than atheists. While secular thinking thrives in science and the academies, it certainly hasn't replaced faith in human affairs. But religiosity does have a new, powerful rival; one, moreover, that performs very similar functions, and makes irresistible claims on our attention. It's called the internet.

Where religion meets the smartphone: Pope Francis with an audience at Rome's Vatican City

Put yourself into the great intellectual flourishing of 8th Century Baghdad, or of Medici Florence. In such places, religion was the air you breathe, the water you drink, the underlying code to all social interaction. The internet does the same for us today: cyberspace is everywhere and nowhere, the background noise made tangible by smartphones, those wizard-like gadgets in our hands.

The transcendental realm to which the Medicis referred citizens was painted on the ceilings of their beautiful churches, and written into the walls of their palaces. And what is YouTube, that digital Narnia, if not a transcendentally different realm?

Modern congregations

The congregations of antiquity are paralleled today by communities assembling online, from the private WhatsApp group that organises a surprise hen party, to the gatherings of thousands on a Facebook group dedicated to marmalade. These modern congregations are weaker, in not being based on felt, real-world connection; and their participants often belong to many congregations, where the religious would belong to one.

But the aim of the congregation has always been solidarity and communal piety, expressed through prayer, in awe of some superior force. I don't for a minute claim that a WhatsApp group formed around a hen party is the same thing; but in those product launches for Apple products that the late Steve Jobs would lead, most of which are still on YouTube, I see nothing short of religious fervour.

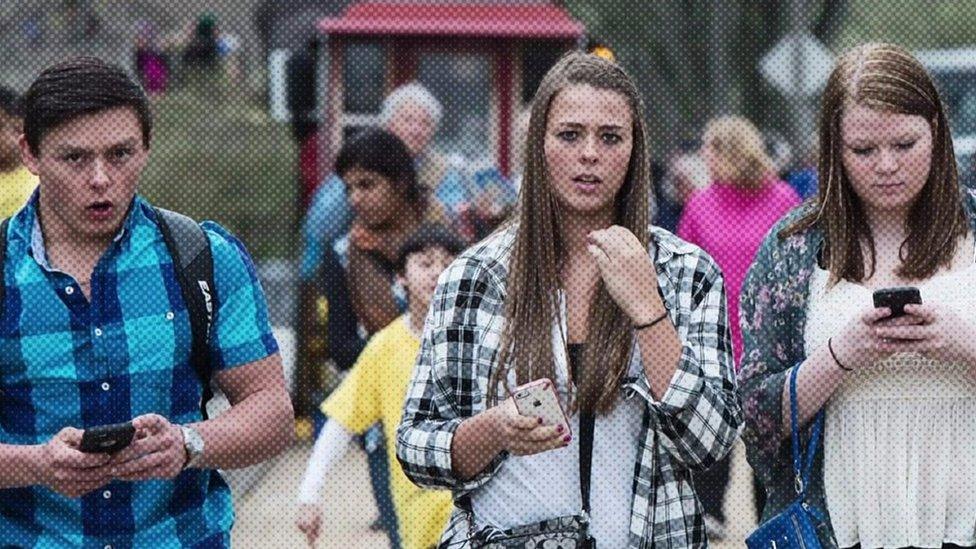

People across the globe are often glued to their mobiles

And not least because, just as religion found its expression through hierarchical institutions atop of which was sat a priesthood, so undoubtedly has the cult of Silicon Valley in particular given us quasi-leaders. What was Jobs, that Zen Buddhist, if not a spiritual guide to Apple's employees, inspiring almost unconditional devotion? What is Mark Zuckerberg, if not a utopian leading a mass movement, who wants all humanity to be part of his scheme? The priesthood had their holy texts. Today's tech evangelists find the meaning of life in code.

In The Essence of Christianity, his critique of religion published in 1841, Ludwig Feuerbach, perhaps the most important of the Young Hegelians, said religions created alienation, by distancing humanity from all that is best about our species, by locating it in a celestial never-never land. Most people of faith would dispute this of course. Yet Karl Marx adopted Feuerbach's idea, by transferring it from God to Money, claiming it was capitalism that created alienation.

Look at yourself...

Marx also imbibed Feuerbach's scepticism toward religion. One of his most quoted, but least understood sentences concluded that religion is "the opium of the people". Look at your teenager this evening, glued to social media. Better still, look at yourself, twitching if you don't have your smartphone to hand. What is it stored in there, amid the circuitry, data, addictive material and astonishing engineering - if not the opium of the people?

This is an adapted version of an audio essay for the BBC World Service. If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from BBC Radio 4.

- Published3 August 2018

- Published4 September 2017

- Published20 March 2015