Olafur Eliasson: Will Gompertz reviews the Danish-Icelandic artist's show at Tate Modern ★★★☆☆

- Published

This week's review is different. It is, as they say in the land of promotions, a two-for-one.

We are looking at Olafur Eliasson's new exhibition at Tate Modern from two perspectives: mine, and further down this page, Laura Hackett's (winner of the Radio 4 Today programme's student critic of the year award). We see things a bit differently…

There are few crystal balls as opaque as the one into which museum folk stare to see how many punters might turn up to a forthcoming exhibition. Words like "blockbuster" or "niche"' get bandied about by curators, marketeers, and Dave from finance (whose opinion is never sought and ignored when proffered).

In my time working at the Tate I sat in countless such meetings. Sometimes we got it about right. Sometimes we erred (too high for Dalí & Film, which was a turkey; too low for Edward Hopper).

But there was one occasion in 2003 when we truly excelled ourselves.

Our guesstimate for an installation in Tate Modern's Turbine Hall by an unknown Nordic artist was so spectacularly wrong that we were left with no other choice but to blame Dave.

We thought around 100,000 people would come to see Olafur Eliasson's The Weather Project during its six-month run. Of course, we hoped for a few more because it had been very expensive creating the giant sun effect in such a big space (lots of mirrors on the ceiling).

But we had to be realistic.

The Weather Project, 2003, saw representations of the sun and sky dominate the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern

In the end over two million visitors came to see and experience what would become the most famous piece of immersive art in the world.

It was epic in every sense: an instant masterpiece that was the making of both Tate Modern and Olafur Eliasson.

Sixteen years later he returns to Tate Modern with a career retrospective that doesn't include a re-installation of his giant, misty "Sun", to the huge and obvious disappointment of a couple of London cabbies to whom I was talking.

However, it does have some other notable pieces of his signature immersive art.

The best of which by some distance is the aptly named Your Blind Passenger (2010), which is the Danish term for a stowaway. It consists of a long walkway of bright, white fog that makes seeing much beyond your outstretched arm impossible. If you're a skier or a hiker, you'd call it a white-out: if you live in Beijing now or were in London in the '50s it is reminiscent of dense smog: a peasouper.

Your Blind Passenger, 2010, takes you through a corridor of dense fog, which the artist says helps "you realise that you are not completely blind, you have a lot of other senses which start to kick in"

Except, the environment Eliasson has created is sweeter (literally, the mist is sugar-based) and gentler.

You will be disorientated and restricted but the discombobulated feeling is more of purity and wonderment than fear or repulsion. Keep walking and the optical effects start happening.

But you must be alone.

If you see someone else the impact is severely diminished.

It is typical of Eliasson's thoughtful, quietly provocative art, which when at its best stimulates your senses and your mind.

That's the case with Your Uncertain Shadow (2010), another stand-out work in an otherwise slightly disappointing show.

It is exploring his primary artistic concerns of light and colour, environment and perception. You walk into a white-walled gallery that doesn't look much until you stand in front of five floor-mounted coloured spotlights and look on the back wall. There you will see, and be enchanted by, your silhouette writ large in five overlapping pastel shades.

Your Uncertain Shadow (colour), 2010, challenges the way we see our environment

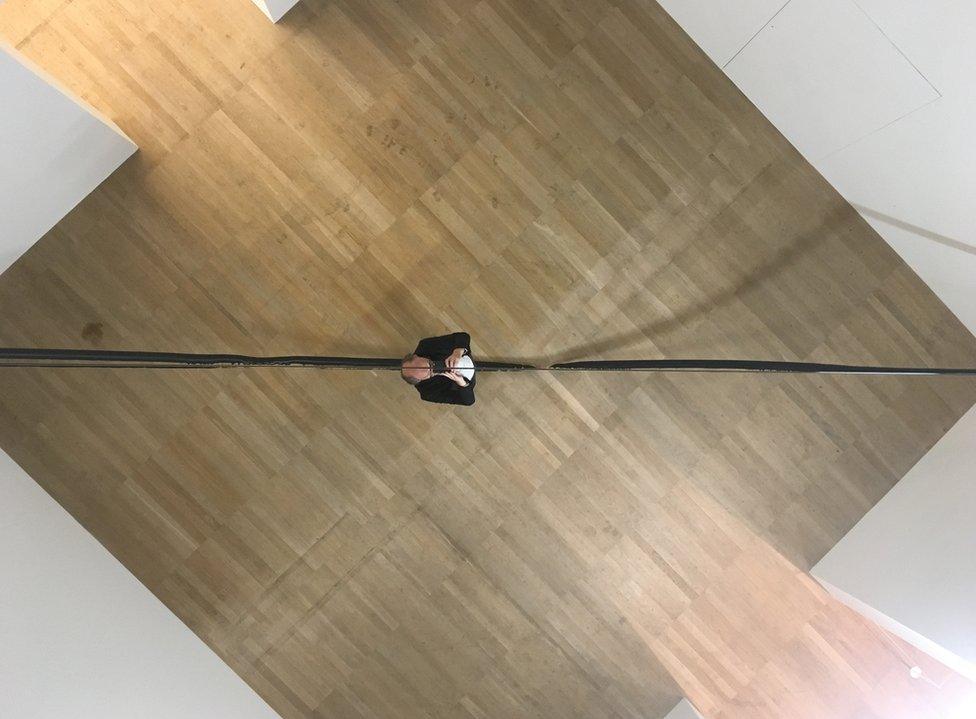

Will Gompertz getting into Eliasson's art

Eliasson is at his best when there's an element of playfulness in his work, which is evident again in Beauty (1993), a black-box room with misty water falling from the ceiling through beams of light.

He is less convincing when being overly earnest, as with the scaffold waterfall situated outside the building.

Beauty, 1993, evokes the meteorological phenomenon of a rainbow inside the show

On the terrace outside Tate Modern you see Waterfall, 2019, a new installation measuring over 11 metres in height

There's no doubt he is a very good artist with important things to say.

But this show somehow fails to capture his spirit. It feels disjointed and thin, which is incredible given how prolific Eliasson has been over the years.

Maybe Dave has decided to flex his muscles and imposed some budget restrictions?

Laura Hackett, BBC Radio 4 Today's student journalist critic of the year

Eliasson's exhibition doesn't have an obvious entrance. There are doors, yes, but the viewer's experience begins long before that. Outside, you can't avoid his waterfall. With its scaffolding laid bare, the huge sculpture is a testament to the human power to get inside nature and remake it in our own image, but also nature's power to get inside us. Stand beside it and close your eyes, and the busy urban landscape is replaced by an elemental non-human scene.

The waterfall stands beside a Tate cafe, and if you're peckish you can enjoy a set menu created in conjunction with the chefs at Studio Olafur Eliasson - vegetarian offerings designed to be shared and eaten slowly. The philosophy behind this exhibition has entered you before you have really entered it.

If you take the lift, you might wonder whether the museum's lights are faulty, but you are in a rebirth of Eliasson's 1997 Room for one Colour - mono-frequency lamps reduce everything to yellow and black, and the uncanny atmosphere continues in the blindingly bright foyer.

In Room for one Colour, 1997, the space is bathed in light from mono-frequency lamps

Eliasson's art is not contained to the exhibition space; it spills outside, refusing the idea of a frame.

Inside the exhibition proper, some of the Scandinavian artist's best known pieces from the past 20 years find new meaning.

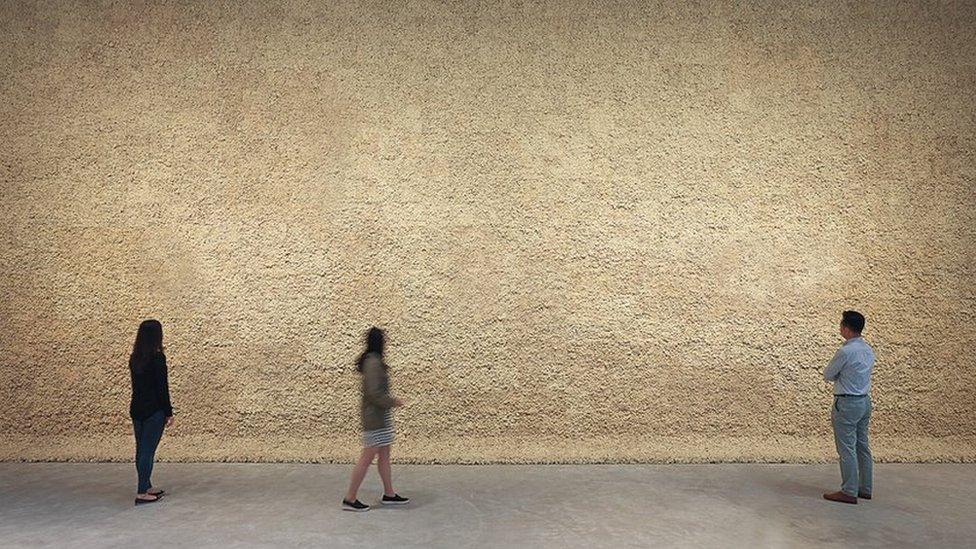

The giant moss wall, which will dry out, be watered, and re-grow over the course of the exhibition, has a new sense of urgency in the context of climate crisis. Its overwhelming size is concurrent with its vulnerability, and a sense of misplaced-ness in this pristine environment.

Moss wall, 1994, shows the Outdoors being brought Indoors

But often it's the viewer who feels out of place. Water trickles outside the windows, to simulate rain, serving as a reminder of the falsity of our constructed indoor worlds. Buildings are recalibrated as not only forces of protection, but also imprisonment, separating us from the natural world.

One room is empty, with bright white walls, until you walk in and your silhouette appears in five colours. This piece is titled Your Uncertain Shadow - you might create the art, but your silhouette is split up. You lose structural integrity. Another features a rotating irregular blotch of light which manages to be at once cosmic and embryonic, unbearably close and unimaginably distant.

If the posters are anything to go by, Your Uncertain Shadow is the leading image of the exhibition, but for me the stand-out piece was Beauty, a darkened room with a spotlight shining through falling mist. As you tip-toe around (this is a space which implicitly demands silence), you might catch a glimpse of a rainbow, and watch the mist change pattern and direction.

Eliasson says Beauty demonstrates our capacity to see different things but still be together. It does this, but even more powerfully, it manages to create a space which is both inside and outside, not simply in-between. It forms the climax of an exhibition whose resounding message is the mutual implication of mankind and our environment, an implication which Eliasson believes should be celebrated, but also recognised as a responsibility to protect the world we live in.

★★★★☆

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external