Where were you when man first landed on the Moon?

- Published

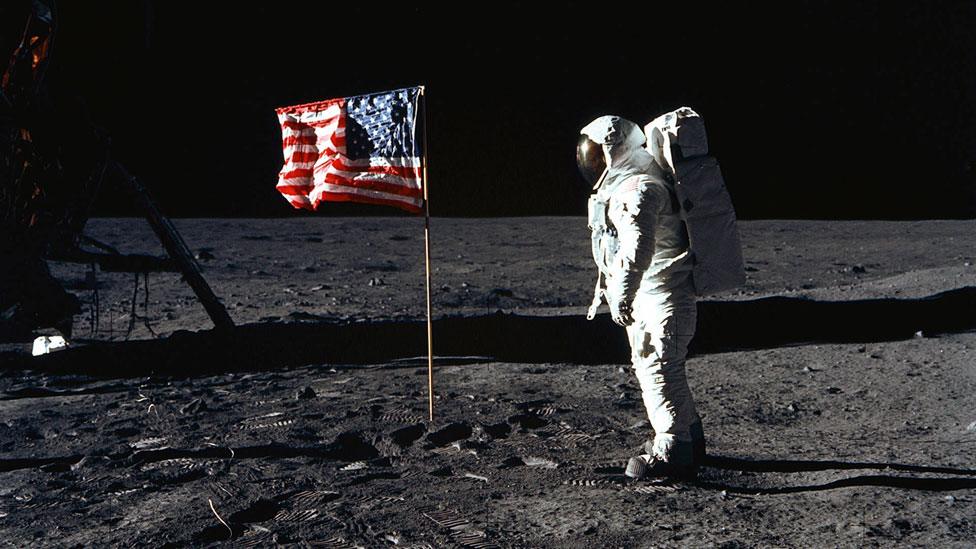

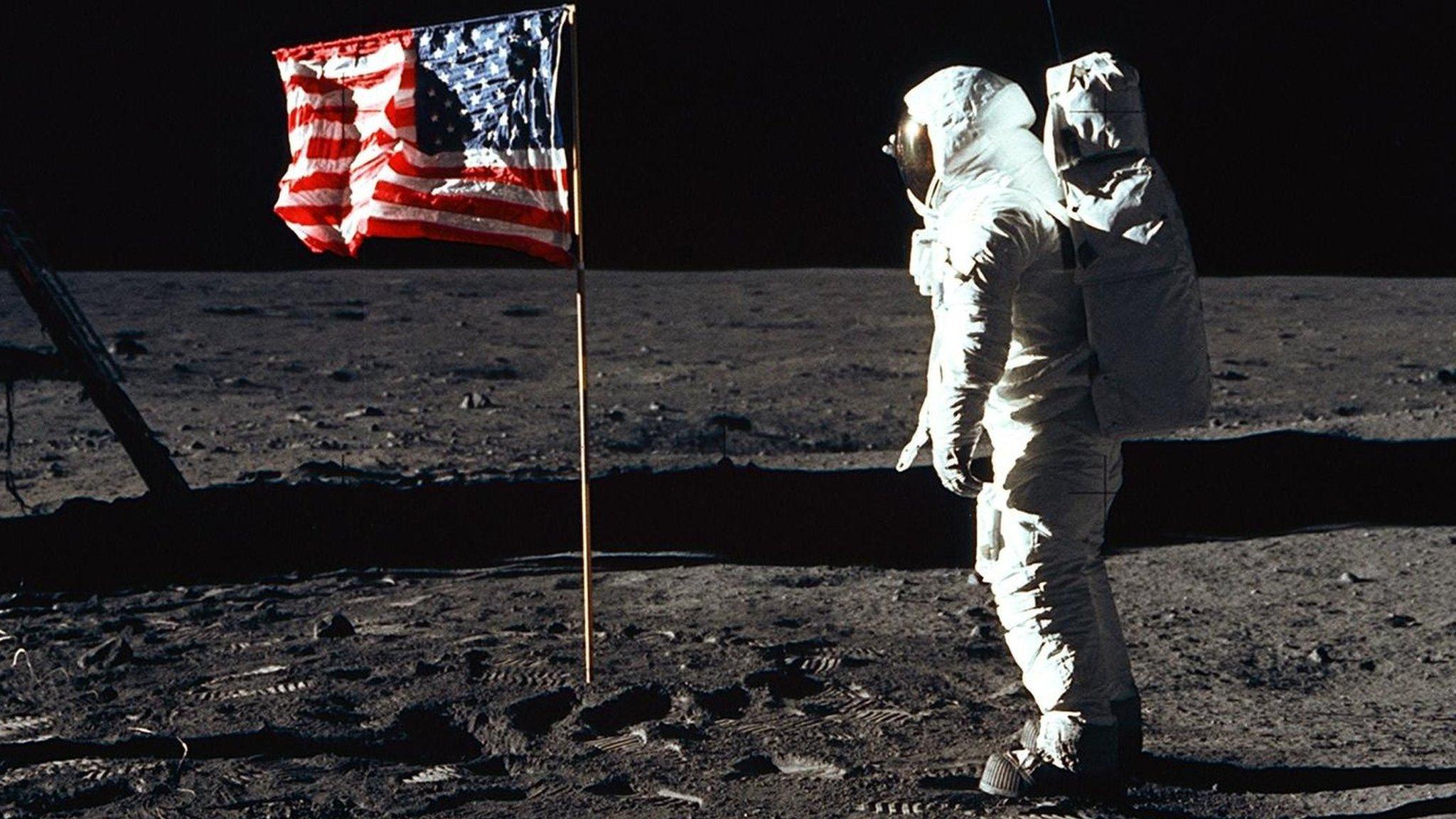

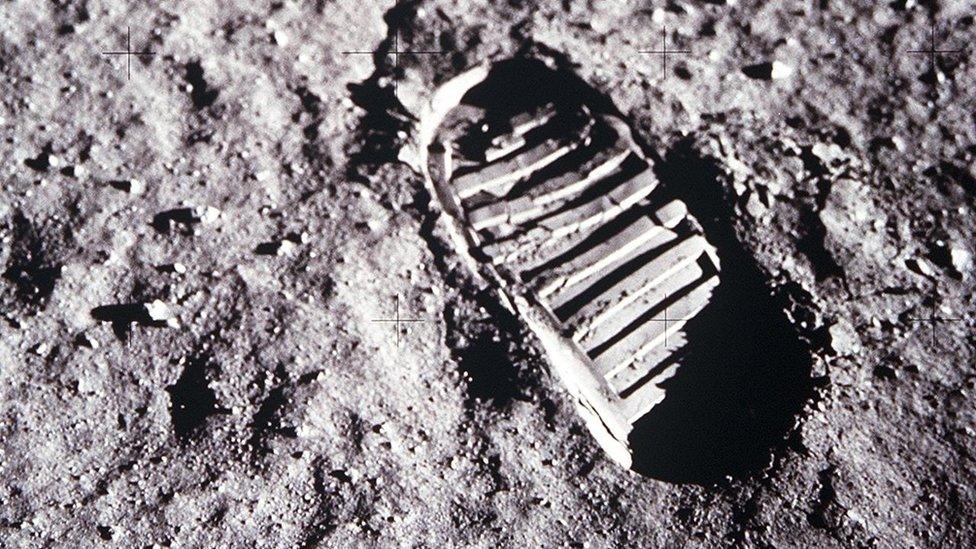

Buzz Aldrin pictured on the Moon by fellow astronaut Neil Armstrong

It is claimed that 22 million watched the coverage of Neil Armstrong's historic moonwalk in Britain on the day, but the number who actually saw it live was probably rather smaller because it was an event that unexpectedly took place in the middle of the night, UK time.

But for many who did manage to make it to the big moment, it was life-changing. Fifty years on, we speak to three people who have been contributing to a UK Space Project/AHRC project, Moon Memories.

It was not part of the plan. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were supposed to be settling down for a rest but the BBC's Apollo 11 programme presenter James Burke listened in to the communications from the lunar surface and realised they had changed their minds and were preparing to step on to the Moon. However, no-one could tell them when they would emerge. What should have been a short update programme at 11:32pm became the BBC's first all-night broadcast. Burke was a bit tense. If he had got it wrong, there would be consequences.

In Dagenham, Jackie Burns was 11 years old and sitting in the gym of her school. She, like most of her friends' families, did not have access to a television and so the school had opened its doors on a Sunday evening to parents and children. They had watched the coverage of the touchdown and the plan was to go home and return at seven o'clock to watch the first moonwalk. When news came that it might happen overnight, everyone decided to stay. The problem was there was nothing to watch other than the BBC's presenters talking among themselves.

"The children got very bored and they were getting up and running around," says Burns. "And the parents were chatting amongst themselves and the noise volume was going up. And there I am dodging trying to see and I am getting so frustrated with it, because I so wanted to see it. I burst in to tears."

In Ashford-in-the-Water, a small village in the Derbyshire Peaks, 13-year-old Nigel Shadbolt was heading downstairs. The rest of the family had long gone to bed but he did not want to miss the crucial moment.

"I was thinking I'd never been up this late," Shadbolt recalls. "We had a grainy Philips TV, I was crouched down in front of it thinking how loud can I have it because I did not want to wake people upstairs. I was just incredibly excited and also worried that continental interference would do for the whole project because in those days the TV signal would come in and out in the summertime."

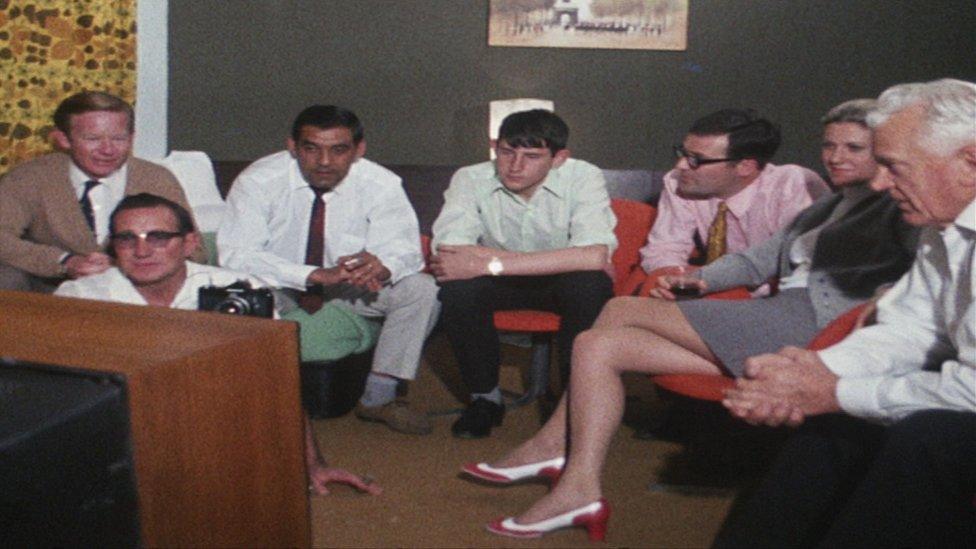

Millions gathered round televisions across the world to watch the moon landing

Even Pope Paul Vl was tuned in

Networks around the world had been trailing this for weeks as the TV event of the century. It was the culmination of 13 years of competition with the Soviet Union that began with the launch of Sputnik in 1957. In July 1969, both America and Russia sent rockets to the Moon but the world has largely forgotten the unmanned Luna 15 that crashed on to its surface on the same day that Neil Armstrong first stepped out of the lunar module. And throughout it all the astronauts were filming the journey but the pictures that were beamed back live were dark, grainy and black and white. Nevertheless, for a generation this was a shared global TV moment.

In the studio, James Burke, Patrick Moore and Cliff Michelmore were trying their best to keep things going without any pictures from the Moon. Finally at around 3:45am Burke began to hear definite signs that the astronauts were about to open the door and swing the camera out to show Neil Armstrong step on to the Moon. There was one overriding thought on his mind.

"The worst thing you can do is talk when an astronaut is talking," Burke explains. "And I had horror dreams the night before that he would be walking down the steps and he would open his mouth to say something and I would talk over the top of it so when he went out of the door I shut up and the control gallery asked if I should perhaps say something and it was at that point he said 'that's one small step.'"

However, the image of the Moon surface was at first upside down. And when it did right itself it was dark and grainy. Many of the shots we see today have been digitally enhanced to give us a rather better image than viewers saw in 1969. But for one 11-year-old Chris Lee who was sitting with his father (his mother and brother had long gone to bed) it was a moment he would never forget.

"I knew at that point that's what I wanted to do," says Lee. "I wanted to be involved in that side of life, those programmes, looking out in to the Universe."

Chris Lee, from the UK's Space Agency, was inspired by the moon landing as a child

A few years later Lee was studying space engineering at University and is now head of Science Programmes for the UK's Space Agency overseeing Britain's contribution towards a planned lunar space station.

Shadbolt is now a Professor of artificial intelligence (AI) at Oxford University.

"I think you can talk to an awful lot of people from my generation who were inspired by those extraordinary achievements."

And as for Burns?

"It inspired me but the best I could hope for in those days was to be a clerk or typist," she admits.

However, 50 years on everything has changed, Jackie is now a space artist and makes a living creating scientifically accurate artworks of planets, rockets and of course the Moon.

"It was an amazing thing to see and I was so affected by it.

"I was determined to get a bit of the action even though I was a woman and I knew I would always be an outsider of science but I was determined to get there somehow. And I did."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published10 July 2019

- Published12 May 2019

- Published16 July 2019