William Blake: Will Gompertz reviews 'imperfect' Tate Britain blockbuster ★★★☆☆

- Published

The strangest thing happened to me at Tate Britain's William Blake exhibition; something I'd not encountered before, nor even considered possible.

Nothing dramatic, like falling into a trippy hallucinogenic state brought on by seeing Blake's fearful painting The Ghost of a Flea (1819), a gothic, slithery depiction of a vile character who appeared before the artist as a vision.

My experience was much more prosaic. Most un-Blakeian, in fact. I entered the exhibition as a lifelong fan, a fully signed-up Blake-head, but left some time later faintly irritated by the fellow. That's not his fault, nor mine, I think. It is down to the way his work has been displayed.

There are some artists who can withstand the mega-blockbuster expo show with its department store aesthetics of huge interconnecting rooms for folks to wander through and browse. A David Hockney or a Bridget Riley can survive the TK Maxx treatment - their paintings are big and bold and colourful and can be enjoyed when seen from a distance.

It is the largest exhibition of Blake's work for almost 20 years

But there are other artists, and William Blake (1757-1827) is certainly one, whose detailed, intense images and poetry are not suited to being shown in warehouse-sized spaces. His work is all about atmosphere and otherness, delivered with a psychologically-charged flourish. There's an intimacy to Blake that is compromised when shown on the massive scale of the Tate show. It kills the mood.

To the curators' credit they have attempted to create a Georgian aura in the vast modern rooms by dimming the lights and painting the walls in rich, dark colours. But covering the entrance foyer leading to the exhibition in a hideous bright red was a mistake: a block of vulgar, shouty colour setting completely the wrong tone for this most sensitive and ethereal of artists.

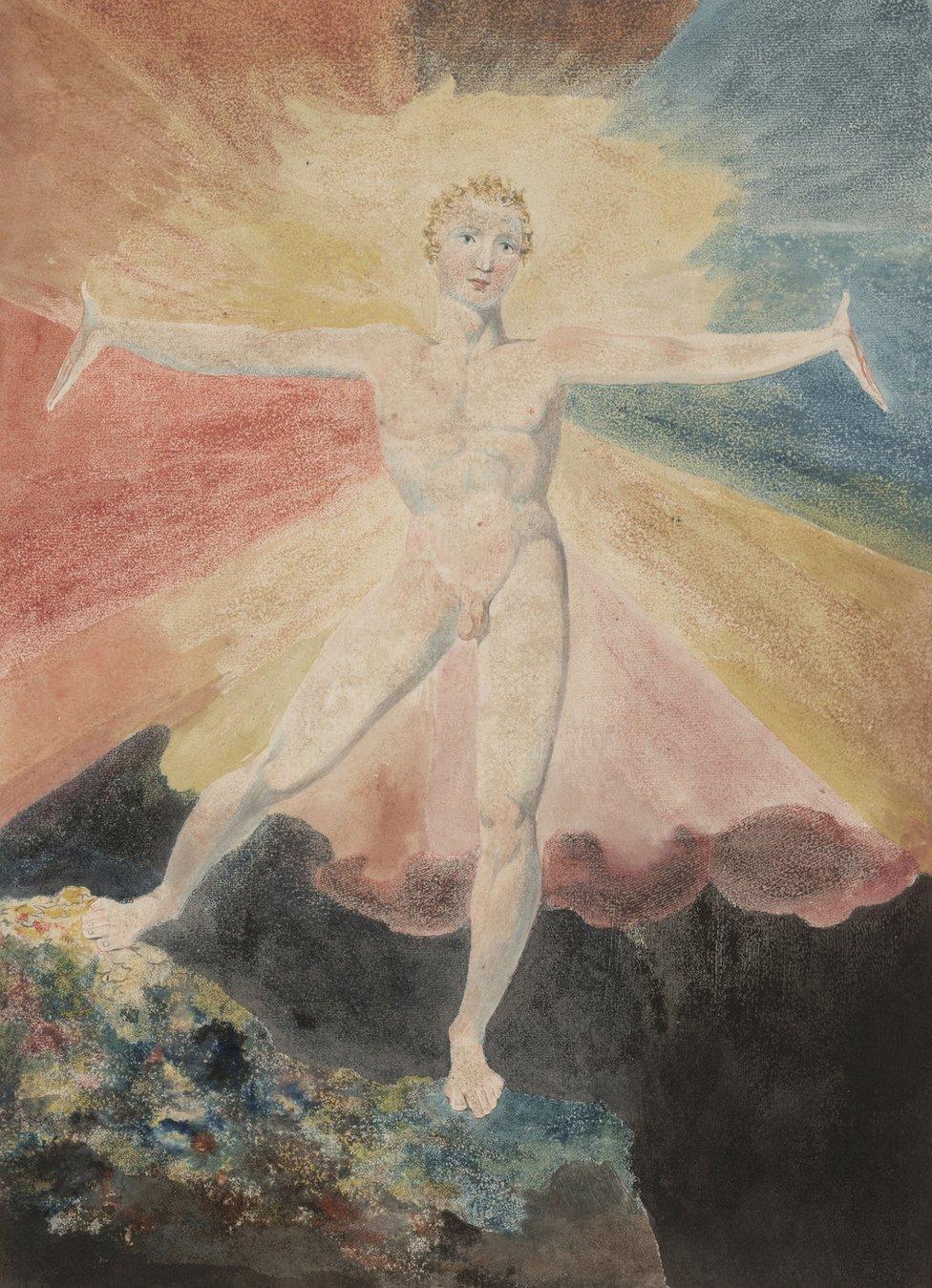

William Blake's Albion Rose, circa 1793

The great beauty of Blake's paintings, prints, and coloured engravings are their exquisite intricacies and tonal subtlety. That is immediately obvious when you see the first image in the show, Albion Rose (1793). A naked young man stands atop a mottled rock, his arms outstretched in front of a glorious spectrum of colours heralding a new dawn. It is an optimistic, joyful picture: a jolly "welcome to the show!".

Thereafter, the exhibition is laid out broadly chronologically, with abundant biographical detail. His family ran a hosiery shop and haberdashery in Soho selling "all kinds of baizes, Flannels, etc etc". They indulged young William's interest in art. He was apprenticed to an engraver before enrolling as a student at the Royal Academy of Arts.

There's a lovely, delicate drawing of his wife, Catherine, who is given a Best Supporting Spouse role by the curators. She shared his artistic burden by colouring some of his work, helping with the printing and finishing off some drawings. Somebody had to. As she once said of her husband: "I have very little of Mr Blake's company; he is always in Paradise."

The Ghost of a Flea c 1819, graphite on paper

And that's where we want him. Away with the fairies, free to see his visions; letting his extraordinary mind and spirit roam at will. That is the essence of Blake, it's what makes reading his poetry alongside his fabulous illustrations so exciting.

The good news is you'll see plenty of his illuminated books in this show, including his famous Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794). They are all terrific.

But the curators' desire to contextualise every last part of Blake's output by introducing his patrons, his business practices, the work of his contemporaries - because there's plenty of space in those big rooms to fill - means the mystical, magical nature of the work is usurped.

A visitor to Tate Britain in front of a William Blake projection

Blake is all about the possibilities of the human imagination. He offers us an escape from the dull realities of everyday life. He challenges us to think beyond the rational and the assumed with fantastical creations such as The First Book of Urizen (1794). We don't need to know what his bank account looked like at the time, or where he happened to be living. The work can speak for itself without a nagging commentary dragging into the mundane.

There are moments when Blake is allowed to breathe. Most notably in the room in which 12 large colour prints hang, which the artist described as "frescos". They include some of his finest images, including the mesmerising God Judging Adam (1795), and grotesquely brilliant Nebuchadnezzar (1795).

After that, things take a turn for the worse, with an unconvincing mock-up of his disastrous 1809 exhibition, to which almost nobody came, and those who did largely kept their hands firmly in their pockets. This is followed by a dreadful room in which massive digital images of Blake's paintings are projected onto the walls because, we are told, that is what he always wanted. Not like that, he didn't. He'd be appalled.

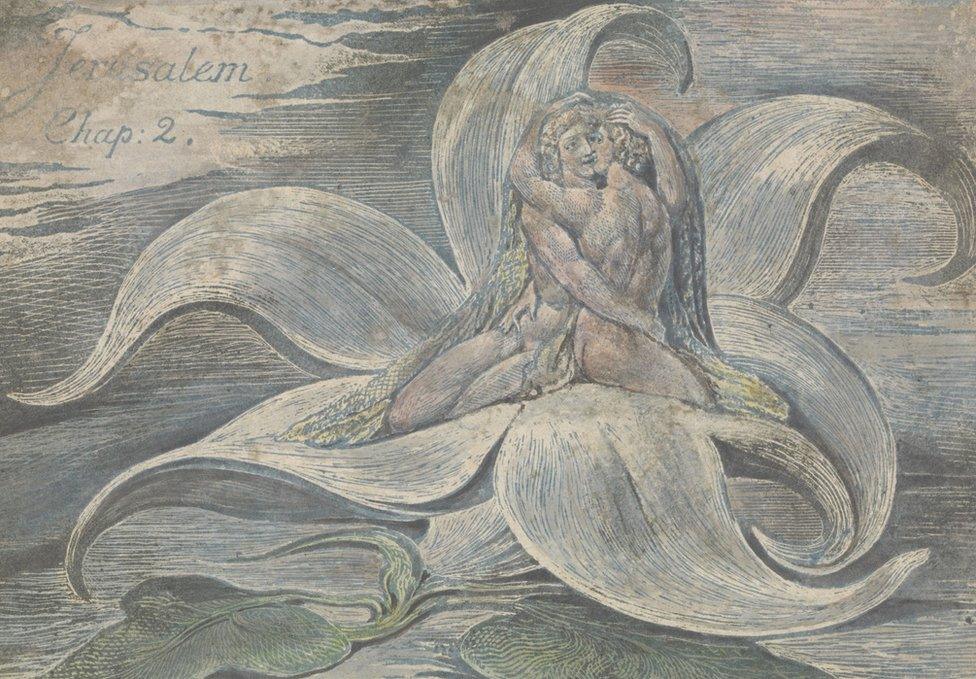

Jerusalem, plate 28, proof impression, 1820, relief etching with pen and black ink and watercolour

There is something of a recovery after the curatorial theatrics, with an excellent display of his illustrated book Jerusalem (1820). Nearby are his late watercolour illustrations of Dante's Divine Comedy (1824-27), which is a marriage made in heaven, not hell.

By this time, you have seen and read so much Blake, and seen and read so much about Blake, that your head is spinning. It's too much, really. He is a very fine artist, like a very fine wine; not one to overdo. There's a danger of the palette becoming dulled, any sensational radiance diminished.

Nevertheless, and notwithstanding my gripes, I would still urge you to go to this imperfect show. To have so much of William Blake's psychedelic imaginary world laid out before you is a once-in-a-generation occasion and not to be missed.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external