John le Carré: 'Politicians love chaos - it gives them authority'

- Published

The author's latest book is set in the political turmoil of 2018 London

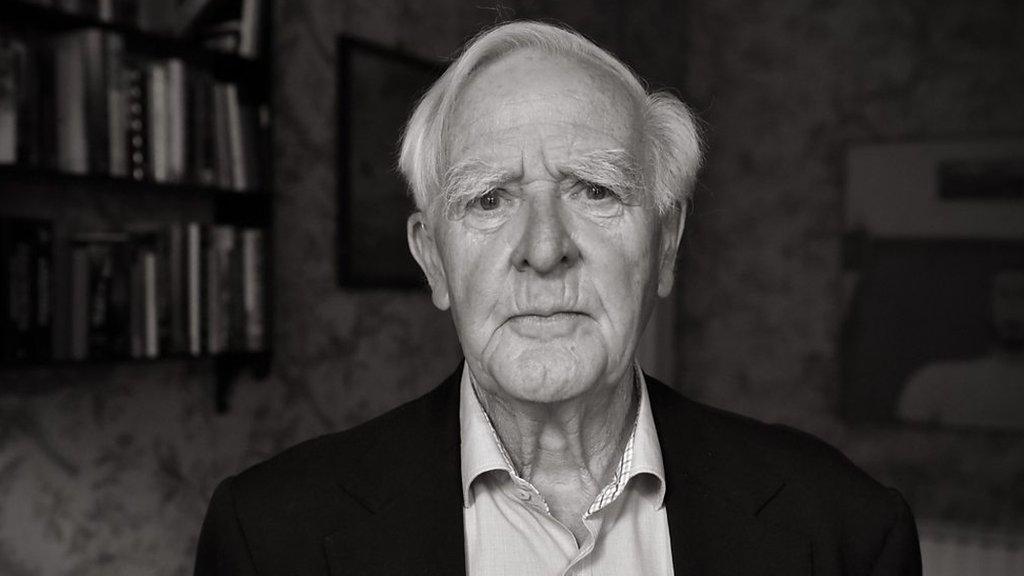

Ahead of the release of his latest novel, novelist and former MI6 spy John le Carré talks to the BBC about our world leaders and why "human decency" must prevail.

A chance meeting in a badminton club, of all places. A few words. A connection made. Nat, who's disturbed by the chaotic politics of the moment, finds himself spinning a web in which he knows he'll be caught. Spies, loyalty and deceit. John le Carré is back.

His latest book, Agent Running in the Field, is his 25th novel and it reveals a writer - who'll be 88 the day after the book comes out - whose preoccupations with the meaning of patriotism haven't faded with the years, but become sharper. This is not a crude story about Brexit, but there's hardly a page in which subtle and insistent questions aren't asked about what kind of country we are, and may become, in the midst of this turmoil.

We talked at length in the summer. "It would be impossible to write at the moment without speaking from within the state of the nation - we're part of it, I'm part of it," he said. "I'm depressed by it. I'm ashamed of it and that I think communicates itself in the book."

The BBC's adaptation of the author's The Night Manager won three Golden Globes, three Baftas and two Emmys

Yet this story - "it's a book that's supposed to entertain. I believe it does. I'm a storyteller" - is as much about the past as the present. We talked about the early days, writing his breakthrough novel when he was still serving in MI6. "If I go right back to The Spy Who Came in from the Cold we're dealing with the same conflict between personal object of personal obligation and state obligation what you owe to society in its organized form."

That theme, on which he's composed so many variations over more than five decades, has become more disturbing through the years. The strange simplicities of the Cold War - the two sides knew each other for what they were - have given way to a more puzzling mix of loyalties. For a writer like le Carré, it's as if events have conspired, painfully, to make his point.

He's never afraid to pose the most difficult questions. "If MI6, by accident or design, came upon absolutely irrefutable evidence that Trump had been up to no good in a big way in Russia, what would they do with that intelligence? And, incidentally, what would our leaders do?"

Behind the intricacies of this story, cut from the same cloth as many of his finest books, lies a fear that such questions can't be answered in the way they once were. He produces, as ever, some sparkling throwaway lines that spring off the page. The president of Russia and the United States are talking, and Putin "smiled his jailer's smile".

Russia's President Vladimir Putin and his US counterpart Donald Trump met at the G20 Osaka Summit in June

A talk with le Carré is always invigorating. He fizzes with an energy that gets its power from observation, gossip, a fascination with character and from anger too. A long conversation is always punctuated by hilarious anecdotage, delivered with the relish of a true raconteur, but also a sense of melancholy and loss.

We talked about George Smiley - his great character, who made a cameo appearance at the end of his last book, A Legacy of Spies, lamenting the fragmentation of the cultural Europe he'd thought he was defending, and about Peter Guillam who, in that book, also loses some of his faith.

"Both of them were looking at Britain from outside. Both of them had given an enormous chunk of their lives to spying for the cause. Now they're wondering in that book - and indeed in the present book the protagonists are wondering - whether they actually gave their lives for the right cause whether the cause exists anymore."

This explains this novelist's impatient energy, because he shares that angst, especially about the Europe that fascinated him from teenage days, when he fell in love with Germany, its language and culture. It's a place to which his mind is always turning.

(L-R) Actors Benedict Cumberbatch, Colin Firth and le Carré attended the 2011 film premiere of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in 2011

I mentioned that, without giving away much about the plot, it was a book about the nature of decency.

"Funnily enough, it's a word that is used more in the German language than our own these days. It's actually a concept deeply-rooted in German culture and even in their medieval stories, where it's finally the secret. They have had to learn moderation and decency in their lives. And they have to emerge as decent men and curiously enough I think in every book of mine, indecent as I may be in my own life they emerge as decent men, and that is the longing that lies behind the sad truth.

"The longing, and that is a kind of romanticism."

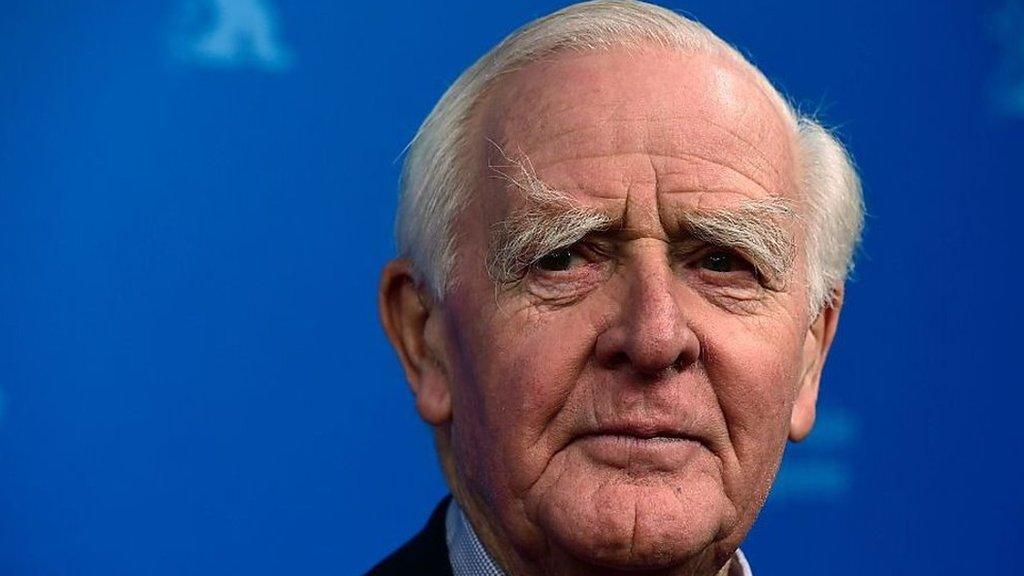

He talked about love of country and his despair at what he considers narrow nationalism - "quite different from patriotism. For nationalism you need enemies."

Le Carré says politicians want to 'fix' the 'chaos'

For a writer who has always enjoyed juggling the obligations of personal loyalty with public duty, it's natural that the current state of politics has given him a kind of painful excitement. It's what he's been on about all this time.

"What really scares me about nostalgia is that it's become a political weapon. Politicians are creating a nostalgia for an England that never existed, and selling it, really, as something we could return to."

And for the political class, a disdain that grows with the years.

"Politicians love chaos. Don't ever think otherwise. It gives them authority, and it gives them power. It gives them profile. The idea that they'll fix it for you." He despairs about what he believes is absolutism on the political right and left, libertarian and Leninist with the same objective. To start again after the chaos.

We return to the book, and its theme - an unashamedly romantic one, that has run through all is work.

'It was Smiley's. Amidst all this turmoil all these lies, and all this dissembling and all that rewriting of history, human decency has to survive."

Agent Running in the Field is published on 17 October by Penguin Books

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published7 September 2017

- Published7 March 2017

- Published6 September 2016

- Published7 March 2017