Troy: Will Gompertz reviews the British Museum's new blockbuster show ★★★★★

- Published

Troy: Myth and Reality at the British Museum is an exhibition that rewards the diligent. To go unprepared is to start watching Game of Thrones half way through Season 7; it'll still make some sort of sense but will generally be more baffling than Prince Andrew's decision to do that interview.

I know this because I hadn't sufficiently mugged up when I went to see it and duly fell at the first hurdle, which is the show's title.

What was myth and what was reality? Was there ever such a man as Homer? Was there ever an epic war with the Greeks? Was there ever a wooden horse? Did Troy even exist?

You need to know this stuff.

Which I do now thanks to the good offices of Alexandra Villing and Victoria Donnellan, who took pity on me and escorted me around their 294-object exhibition.

In the foreground is a marble sculpture of wounded Achilles by Filippo Albacini, 1825

They swiftly put me right on the basics.

Troy did exist.

Well, it did, but even that has been contested. Not least by Homer who reported it had been totally wiped out, a view shared by the Roman poet Lucan, who wrote, "Etiam periere ruinae" - Even its very ruins were destroyed.

That small bone of contention aside, it's useful to know the city was also called Ilion (or Ilium in Latin) - hence The Iliad - is now called Hissarlik, and can be found on the far north west coast of Turkey to the south of the Dardanelles strait near the Aegean Sea.

As for the 10-year Trojan war, they're not so sure. Probably an invention - at least in the way it's described by Homer.

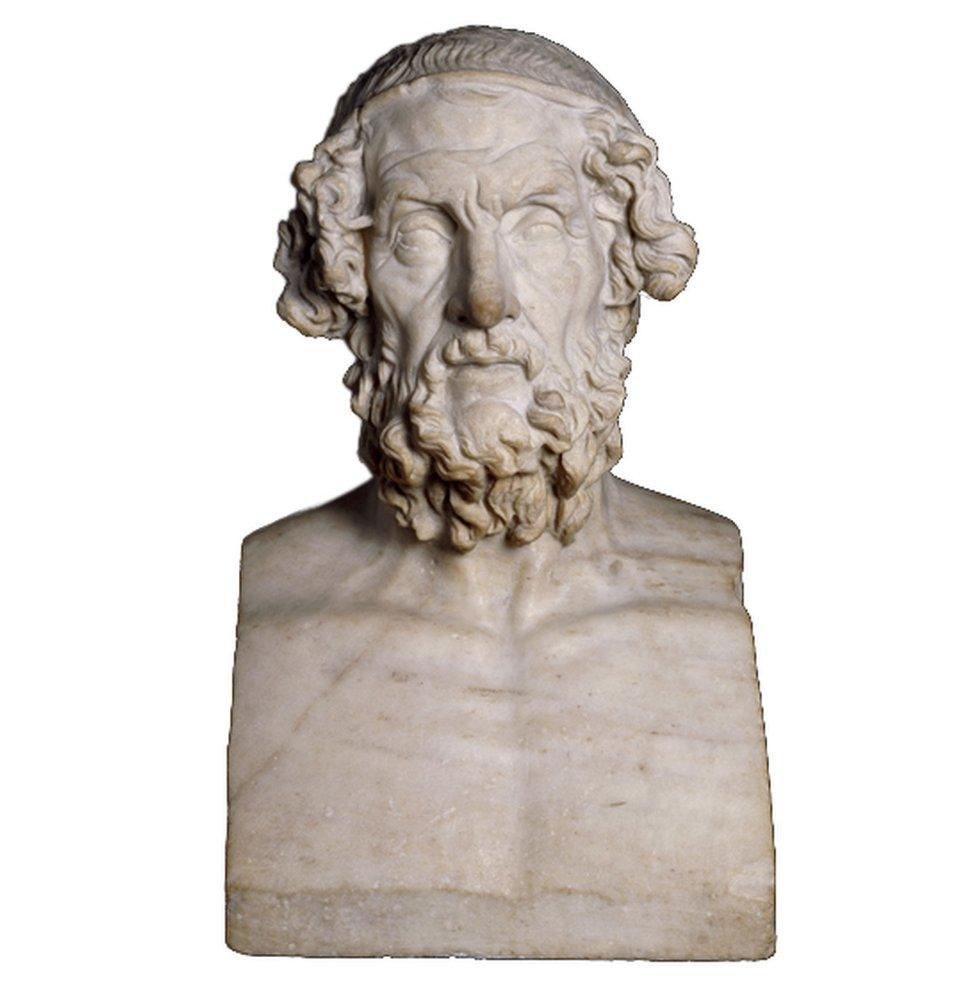

The same goes for the wooden Trojan horse, and possibly even Homer, the great poet of the past.

He might have been a she, or someone else altogether, or a collection of individuals latterly embodied as Homer a single genius because that's how we like our great art packaged.

The truth is we don't know, it is all myth.

I've stood upon Achilles' tomb,

And heard Troy doubted: time will doubt of Rome.

Lord Byron, Don Juan, Canto 4, 101

This bust of the "blind" poet Homer is a Roman copy (2nd Century AD) of a Hellenistic original of the 2nd Century BC

And then there is the reality, which consists of the art and artefacts that make up this encyclopaedic exhibition.

They cover a period of 5,000 years, with the majority coming from the centuries following the fable of the Trojan War, which is thought to have been set in the Late Bronze Age, around 1200BC.

These pots, paintings, carvings, manuscripts, and assorted fragments all have inscriptions and depictions relating to the epic tale. The earliest of which is a small, battered drinking cup (circa 715BC) from Pithekoussai, an old Greek colony in southern Italy. It appears at the beginning of the show and sets a suitably poetic tone, with these three lines of verse scribbled within its geometric decoration:

"I am the cup of Nestor, good to drink from; whoever drinks from this cup, immediately desire of fair-garlanded Aphrodite will strike him."

Drinking cup from the early Greek settlement of Pithekoussai in southern Italy, inscribed with three lines of verse circa 715BC

You wouldn't necessarily know it, but that's a joke.

The point being that Nestor, a Greek king featured in Homer's Iliad, drank from a golden goblet that only he was strong enough to lift, whereas anyone could swig from this little clay vessel.

What was a joke back then is deadly serious now to a contemporary scholar.

The inscription reveals that a small ancient community knew of a story featured in the Iliad. What's more, the pot on which those words appear was not made locally, but in Teos, Turkey, which is near to Smyrna and Chios, two settlements put forward as the birthplace of Homer.

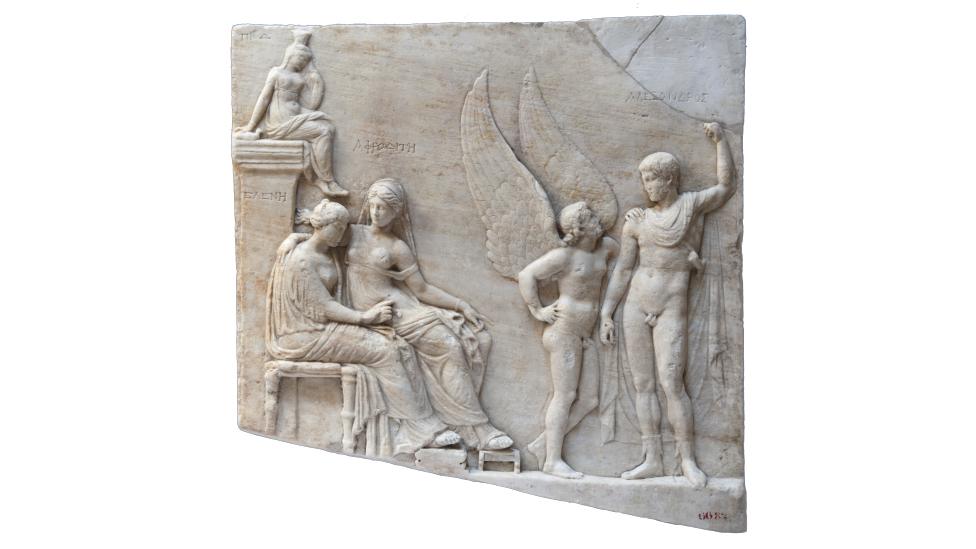

Hanging on a wall not far from the cup is a wonderful marble relief (circa 1st Century BC - 1st Century AD) that gets to the crux of the story. It shows the meeting between Paris (the son of Priam, King of Troy) and Helen (wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta.)

The rendezvous is engineered by meddling gods and is not entirely of Paris's making. He had been asked by Zeus to pick the fairest of three goddesses: Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite.

This sculptural marble relief depicts the meeting of Paris and Helen, assisted by the gods

It is a scene known as The Judgement of Paris, which is shown in several pictures in the exhibition, the best of which is by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a painting from circa 1530, which has an unforgettably charismatic horse looking on.

Paris chooses Aphrodite, who promptly offers to him as his reward, the most beautiful woman in the world, which is Helen. The warmongering gods have done the poor chap up like a kipper.

Of course, he falls for Helen and takes her back to Troy.

The Judgement of Paris circa 1530, by the German Renaissance artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder

There's a wonderful wall-painting (AD45-79) from Pompeii in the exhibition, showing a servant leading Helen to the ship that will take her to Troy. She doesn't look exactly thrilled by the prospect, but her sombre mood is nothing compared to her husband's.

Menelaus is absolutely livid when he discovers that some Trojan bloke has gone off with his missus.

He marshals an army of fellow Greeks to bring her home, and thereby begins the decade-long Trojan War.

Wall-painting showing Helen leaving Sparta for Troy AD45-79

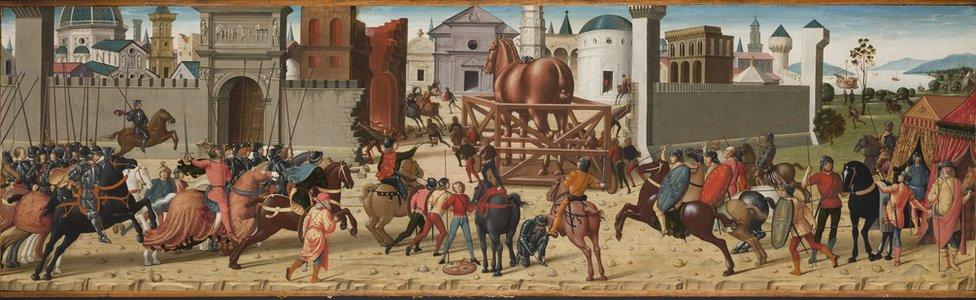

The Siege of Troy - The Wooden Horse circa 1490-95, is one of a pair of panels by Biagio d'Antonio

The Iliad only covers 51 days of the drawn-out battle, concentrating on the last year and featuring all our favourite characters and events.

We see a lot of Achilles. And the Greeks' famous wooden horse, which is elegantly evoked in a bespoke section that leads to the second part of the show, bringing us into the 19th Century and the archaeological exploits of a German businessman called Heinrich Schliemann.

He and Frank Calvert, an Englishman and fellow Troy-head (archaeology was still a largely amateur pursuit in 1870), set out to find the fallen city using Homer's geographical descriptions as their divining rod. The poet had mentioned the Dardanelles, Mount Ida, the islands of Tenedos and Imbros, and local rivers.

They identified a mound at Hissarlik as the spot to start digging. Schliemann was determined to prove not only that Troy was buried beneath the surface, but also find incontrovertible evidence of the Trojan War.

As you will see, if you visit this excellent exhibition, he did very well on the first objective, but fell woefully short on proving the myth a reality.

His years of digging are displayed with a mixture of flair and restraint. The bowls, cups, axes and animal figures are theatrically lit within a shelved structure that represents each layer of the excavation. And so, an object from Troy VII, is shown a metre above one from Troy II. It's a helpful device.

This tripod pot (2550-2300BC) excavated by Heinrich Schliemann at Troy, was burnt black during the Allied bombing of Berlin in 1945

The exhibition finishes with a gallery of paintings showing the Western fascination with the mythical tale.

A Matisse-inspired collage called The Siren's Song (1977) by the African-American artist Romare Bearden is very good.

Eleanor Antin's Judgment of Paris (after Rubens) from 2007 is fun, but does not compare to the Baroque master's painting nearby, The Wrath of Achilles (1630-35).

Wrath of Achilles 1630-35, Peter Paul Rubens

And then there's the William Blake, the Cy Twombly (as you enter the show), and the Elisabeth Frink lithographs.

There is so much to enjoy in this show, it doesn't matter that there is the odd dud along the way - I didn't much like the Anthony Caro sculpture with sound effects as you enter the exhibition, or the Shield of Achilles (2019) by Spencer Finch as you leave - but pretty much everything in between them is terrific.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz