The Cellist: Will Gompertz reviews the Royal Ballet work inspired by Jacqueline du Pré ★★★★☆

- Published

It might sound a bit rich coming from someone not noted for his good looks, but beauty isn't getting the respect it deserves.

Not so long ago it was all the rage.

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant was pro-beauty. He considered it a form of morality.

Einstein said it enticed the inner child out of us.

And wise old Confucius believed everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it.

Bringing it into plain sight used to be the job of artists, authors and composers wearing billowing white shirts with splendid frou-frou collars last seen on Duran Duran in the 1980s. But pop's New Romantics were no match for the relentless march of modernism with its frigid less-is-more dogma and strict no-frills dress code.

I blame Marcel Duchamp.

He was the artist who proposed a urinal as a work of art back in 1917. He chose it precisely because it was, as he said, anti-retinal: an unattractive sight. It was intended as an act of destruction: an enamelled Exocet missile aimed at the heart of a bourgeois art establishment aligned to a political class responsible for a horrific, bloody war.

Marcel Duchamp's urinal wasn't deemed a work of art in 1917 by the Society of Independent Artists, who considered it indecent

It was no time for beauty, Duchamp argued.

If art meant anything at all it should speak the truth about what was happening, which was ugly and base. His toilet scored a direct hit, romanticism was dead. Henceforth, beauty was naff and frivolous; cynicism was the new religion for our secular age. Music became dissonant, literature became fragmented, theatre became absurd, and art turned ugly.

Caught up among the collateral damage was classical narrative ballet, the most romantic of art forms.

Tutus and fairies had no place in the new order. Ballet was dispatched to the art dog house, to be consumed by the people of Tunbridge Wells, or somewhere equally as uncool, where locals dress in brown tweed and mustard corduroy and consider Country Life a magazine not a brand of butter.

To see exceptionally talented dancers express emotions and story through graceful movement is a sensuous experience like no other

And that is where ballet remains, with some of the most beautiful choreography and music ever created written off as elitist and irrelevant.

It's a shame.

To see exceptionally talented dancers express emotions and story through graceful movement accompanied by a full orchestra is a sensuous experience like no other.

It isn't posh or difficult or any more expensive than going to a gig or a Premier League football match.

It isn't stuck in the past either.

The Cellist has just opened at the Royal Opera House in London. It is a new ballet by Cathy Marston telling the true story of Jacqueline du Pré, the prodigiously gifted post-war cellist whose career and life were cruelly cut short by multiple sclerosis.

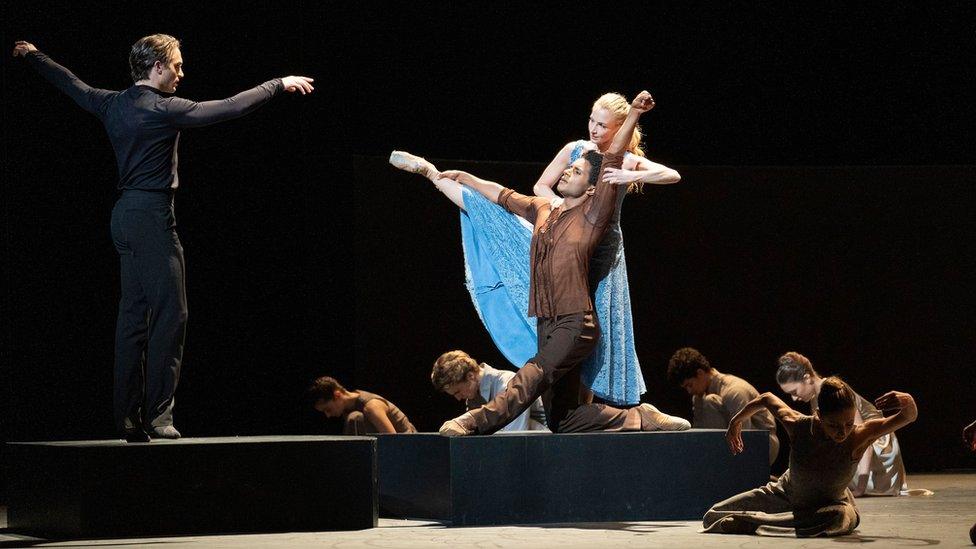

Choreographer Cathy Marston behind Marcelino Sambé, shows Lauren Cuthbertson how to hold her cello during rehearsal

The tragic-romantic tale of love and loss centred around a young woman is classic classical ballet.

The difference here, though, is the subject of our heroine's affections isn't her lover and husband, the pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim, but her instrument: the eponymous cello.

Barenboim gets to play the gooseberry, as he watches his wife enthusiastically pluck her instrument, brought vividly to life by the Royal Ballet's newly promoted principal dancer, Marcelino Sambé.

Lauren Cuthbertson takes the role of Jacqueline du Pré, and, as you would expect from one of the finest dancers of her generation, gives a wonderfully nuanced and intelligent performance.

The gifted and celebrated couple, Jacqueline du Pré and Daniel Barenboim caught the public imagination in the 1960s

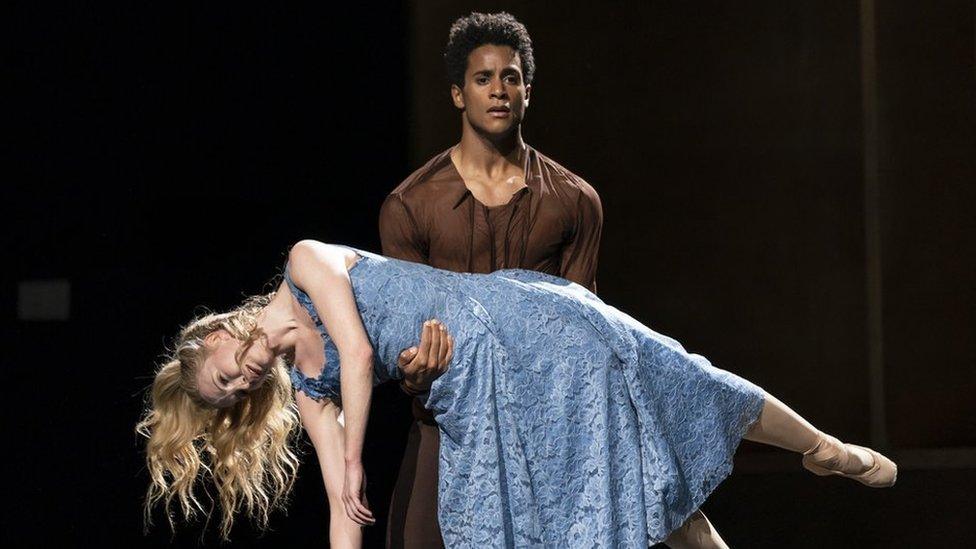

Matthew Ball (Daniel Barenboim) looks on as Lauren Cuthbertson (Jacqueline du Pré) is entranced by her instrument, Marcelino Sambé

The show begins with us meeting a very young Jacqueline (played by a student at White Lodge ballet school) at home with her parents where she is having her first encounter with the instrument that would make her an international superstar by the mid-60s.

Enter Cuthbertson, who stands behind Sambé (her cello) and mimes playing him to the sound of Elgar's Cello Concerto.

It is… beautiful.

Lauren Cutherbertson said the ballet required a different way of thinking, because the female dancer was usually positioned in front of the male

He then lifts her and pirouettes as she maintains a seated playing position, which I must admit, is less beautiful and took my mind back to Duchamp and lavatories. No matter, it is one of very few awkward moments in a piece full of newly found positions, which races through Du Pré's life in 60 minutes.

Barenboim enters the fray, leading to a memorable pas de trois, before dread looms in the form of an inexplicable shake in the cellist's right leg. The transformation from a woman at the very top of her game to one confronting an unknown terror is undertaken with enormous skill and sensitivity by Cuthbertson, whose on-stage chemistry with Sambé transmits her love for him - her cello - with an intensity that makes the hopelessness of her situation profoundly moving.

To have a talent such as hers is a blessing, to have it snatched away so soon by a silent, malevolent condition seems so cruel, to her and us. It is the tragedy of something truly marvellous being destroyed.

Watch: The Cellist's story of love and loss is expressed movingly by the Royal Ballet's principal dancers

That is not a romantic condition, it was a fact of life for Jacqueline du Pré, a reminder that beauty should be cherished not banished. It is not uncool or naff, it is an ideal worth believing in and striving for and appreciating.

That is the message of The Cellist, delivered with aplomb by the dancers and orchestra who accompany them with a score referencing pieces by Elgar, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Rachmaninoff and Schubert.

Beautiful.

Note: The Cellist can be seen on screen in a live link to selected cinemas on 25 February.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external

- Published19 February 2020